Recently acquired by the Chartwell Collection Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Richard Maloy Archive 1996-2001 is a collection of the artists’ art school workings made while studying towards his undergraduate and postgraduate degrees in Fine Arts from 1996-2001. The archive is the basis of All the things I did, a large-scale installation first exhibited at Starkwhite in 2013, which recreated the studio environment of Maloy’s six years of study along with selections of material from the archive, offering an unusually candid view of the artist in early development. In this interview with CIRCUIT Director Mark Williams, Maloy discusses what it means to exhibit this body of work in the present day, his use of the moving image, and the difference between being an art student and an artist.

Mark Williams (MW): Could we begin by describing All the things I did and how it was first presented at Starkwhite in 2013?

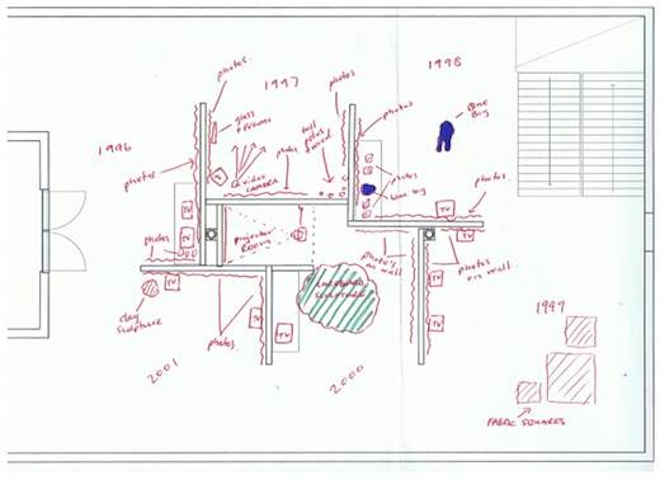

Richard Maloy (RM): It was a large-scale installation, filling the space of the gallery with six booths constructed from white-painted hardboard walls like those common at most art schools. If you entered the gallery and walked clockwise around the booths you could see each year’s progression in the work. Each section contained a combination of material – ephemera, photographs, videos, paintings, drawings and objects – presented as if ‘in studio’ for each year that I studied. A lot of the work had process and performative elements, creating a strong impression of being able to observe the formation of an artist and their practice.

Installation plan for All the things I did (2013) Richard Maloy, Starkwhite. Chartwell Collection Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

MW: A lot of artists are happy to forget their student work. What was the trigger for you looking back at the past, and why the desire to show it publicly?

RM: I have been employed off and on within Auckland art schools since 2009. In 2013 I had an office that looked down into some of the studios, a bird’s-eye-view, seeing second, third, and fourth year studios. This triggered a new line of thinking about developmental stages of learning, and reflecting on my own time as a student.

The other thing that interested me was to expose elements of art school that aren’t otherwise seen. Usually, for end-of-year exhibitions, the schools get tidied up and complete "finished" artworks are on show. You’re missing the process, you’re missing the mistakes and you’re missing the learning.

These ideas might seem quite simple, but they are actually quite far-reaching when we apply them to the world we live in today. As someone who’s trained and worked and made art, I feel like I have a responsibility to deconstruct and show the process of what I’m doing – the paradigm that artists work within.

MW: What do you think All the things I did demonstrates about the studio process within the institution in the late 1990s?

RM: There was nostalgia for, and looking back to, the art and culture of the 1960s and 1970s. The artists I was looking at, the ideas I was investigating, and the types of art history and theory I was learning about as a student at that time, are an example of this. In terms of the mechanics of art making there are a lot of photographic negatives, slides, VHS tapes, sound recordings on cassette tapes—things you just won’t find anymore—or, if you do, they are used as signifiers of nostalgia. Those methods of recording weren’t the cutting edge in terms of technologies available but it was what everyone was using at the time, a mix of analogue and digital. I think in terms of the work belonging to the late 1990s and early 2000s the archive really shows this transformation; it’s a time capsule of sorts, of what it was to be at art school at the end of the 20th century.

MW: It’s interesting that you held on to this material.

RM: Although I majored in sculpture I did photography as part of my studies and was always told never to throw your negatives out, to keep them—this is the idea of the photographer as archivist. So the starting point was sorting and structuring the negatives. And then finding other things in my parents’ barn, in storage, underneath my bed… suddenly the more I looked the more I found. I was surprised how many items there actually were, for example, first-year life drawings. Why did I keep these? I have no idea, but I had; labelled and stored in a cardboard folder I’d made, all taped up and ready to be unpacked. Life drawing is one of the oldest and most traditional forms of art school learning which is no longer a mainstay—with the shift and change in time the old can now help inform the new.

Richard Maloy Archive 1996-2001 (2013) Richard Maloy (installation detail during registration at the Auckland Art Gallery) Chartwell Collection Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

MW: At art school your studio was one of several little cubicles side by side with other artists. How did that model help your practice?

RM: I’m a social person and that interaction with other students was really useful. You had a space that was your own but also, at the same time, you were part of a small community working away at learning art and life together. The particular spaces I had as a student don’t seem like much room now in which to develop a creative practice, but when I was young, just out of high school, merely having two walls and a table and a chair and surrounded by like-minded people was an incredible freedom, as well as an opportunity to make art.

MW: Before the interview we talked about what it meant for you to be studying at the time. You were very conscious of yourself not as an artist, but as an art student.

RM: Not being an "artist" gives you a lot of freedom. You don’t have to worry about making "artwork." Everything that you do can be seen as just drawing or research. Not making "works" gives you freedom to emulate or try what other artists have already done. If you’re working with ideas, materials or processes which already exist, you really just need to do it then look at the results. It is one thing to look at an image but it’s another to act it out, emulate it, and then analyse as a whole.

MW: Let’s talk about the video works, several of which are on CIRCUIT. What was the impetus to pick up a video camera?

RM: I had often used photography to document works and activities and it made sense to step into using moving image. I was never making short films or anything along those lines. I was using video to document an action which usually related to sculptures, paintings or some sort of art activity or process. It was really about extending what I was doing with a still camera. If you look at what I did, it was just about introducing elements of duration in a very pared-back manner. There were no sharp camera movements or editing. I treated the filming very much through the perspective of a still camera. I was attracted to the ability to distance the viewer from the actual work, the "finished product," while simultaneously exposing the process for viewing.

Cardboard Leg (Part 1 & 2) (1999) Richard Maloy

MW: How many video works are in the Richard Maloy archive?

RM: To be honest I’m not sure what’s on any particular recording. There are of course VHS tapes, photos from video shoots, and printed video stills used as photographs, including multiple takes. When I was making this archive I no longer had a VHS player and I had to work from what was written on the tape labels, which was not always exactly what they contained. I still don’t know exactly how many recordings there are, but there are 20 or more VHS tapes with multiple works on each, mostly made in my third and fourth year and a few from my Masters. The Auckland Art Gallery is digitising the material so we should have a better idea of what’s there around the end of the year.

MW: You mentioned that some of the videos on CIRCUIT might potentially be remakes of earlier works?

RM: Shortly after art school there was a period when I showed a lot of videos and the quality wasn’t great so I remade several of them. I also entered those into the archive, but noted in the reference pages that they were remakes. I find I’m often working two steps forward then one step back, so to speak. There are other elements of the project that operate like that; the cardboard constructions can be remade working from the drawings and images of the original. The archive creates a structure for everything to fit within but it doesn’t stop it growing or shifting.

MW: Could you talk a little about the relationship of moving image to other aspects of your practice?

RM: I treat video equally to photography, sculpture and other elements of my practice. Sometimes it can appear on a TV monitor, sometimes projected, or on multiple TV screens. It’s really dependent on the other elements in the show.

Looking back, I was really interested in a democracy of mediums. For me, live performance can become quite problematic in terms of making your audience come and spend time. One of the things I really enjoyed about video is that you can loop it, letting the audience come to the work on their own terms and not be a forceful, dictatorial, artistic voice.

MW: Returning to All the things I did, in preparation for the project did you look at how other artists had constructed their archives?

RM: I have a history with Billy Apple, through working in his studio and assisting on various projects. He has an extensive archive of grey filing cabinets aligned down the centre of his studio and for each year there is a drawer of slides, notes and studio-based ephemera. You can literally pull out any drawer and see deep into the process of who he is, at that moment in time. I was interested in his archive as almost the ultimate Billy Apple artwork.

Working in this environment has influenced my thinking around the concept of "the archive." However, All the things I did is very specific in relation to my time at art school and the politics it draws upon from educational institutions and their processes. I wanted to create an exhibition that visually represented the archive material, and the architectural form of an art school studio was the natural setting.

MW: You’ve said you felt that Richard Maloy Archive 1996-2001 and All the things I did could grow and change over time.

RM: It’s definitely ringbound by that parameter of the art school years and that’s what provides its conceptual framework, both the archive and presentation from it. But I’m definitely open to the idea that works can be added, for example if I find more works or when the work needs to be displayed in different circumstances, I’m absolutely open for it to grow in that way.

MW: You mentioned the freedom of being an art student. Do you still have that same freedom now that you are an artist?

RM: I think so. You have deadlines like a student, and you have things you have to achieve and things you have to do, but at the same time you have a lot of freedom to push and pull your project in different directions. Time operates differently as an artist; you can have ideas and projects that unfold over much longer timeframes. The structural supports are different; they come from a wider range of places, galleries, institutions, museums, curators and, of course, yourself. And I think at art school there’s a fiction which has developed; a concentrated fiction of life as a learning artist. But being an art student or an artist is much the same. You never stop learning.