In her film Treasures left by our ancestors (2016), Ana Iti (Te Rarawa) kneels before a series of exhibition displays at the Canterbury Museum. One of these exhibitions, titled Iwi Tawhito - Whenua Hou, Ancient People - New Land, is dedicated to, in the Museum’s words, tangata whenua and the extinct moa; “the giant, flightless birds they [tangata whenua] hunted.” The other, Nga Taonga Tuku Iho o Nga Tupuna, Treasures left to us by the Ancestors, gives Iti the title for her work. I first saw Iti’s film as part of the exhibition Passionate Instincts at The Physics Room near the end of 2016. Iti kneels for about 15 minutes in front of four displays, while small groups of visitors walk, stand in front of the camera and obscure the view as they look around the dark exhibition space. A sense of stillness and quiet forms, as the visitors’ muffled talking fills up the background soundscape.

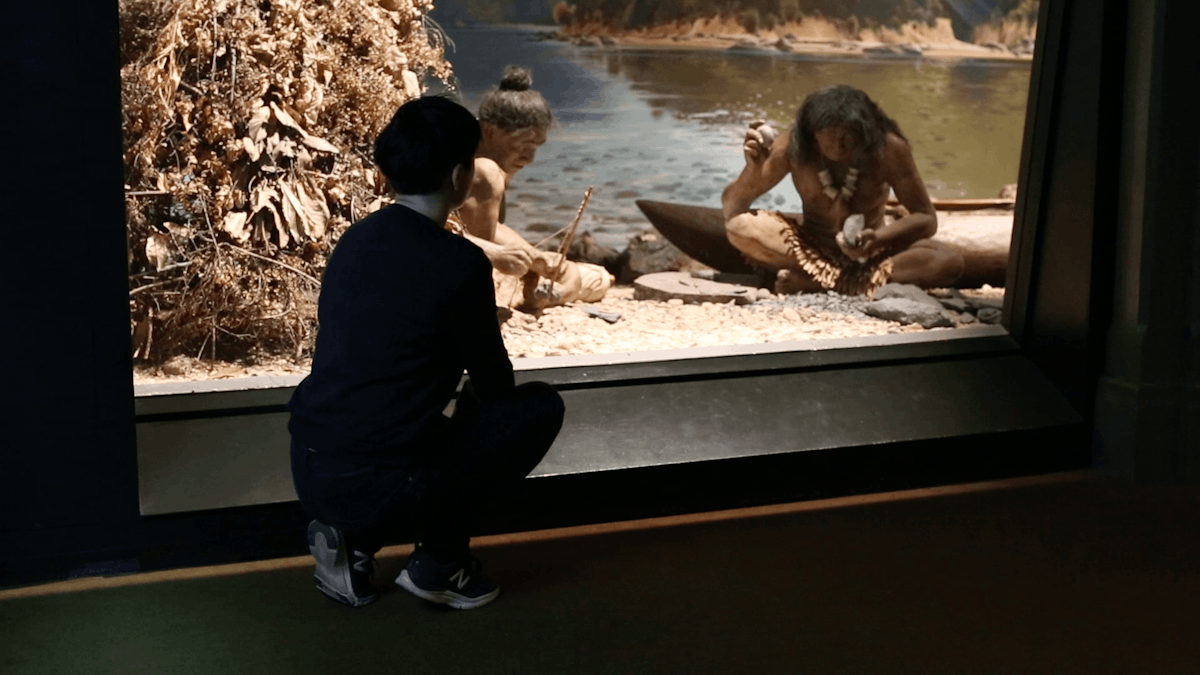

The displays Iti kneels before will be familiar if you have visited the Museum. They are life-sized dioramas of early southern Māori, who are portrayed as they lived 800 years ago in the mind’s image of the people who designed and constructed these displays. In them, people are shown: cave drawing in a mountainside rock shelter; making stone tools and a fishing rope on a rocky beach; hunting moa in a forest; and lastly, cooking on a beach in a sheltered bay. At least in Iwi Tawhito - Whenua Hou, very little information indicates or attempts to explain the history and real complexity of tribal and iwi migrations and origins of the southern Māori population. Instead, a linear, chronological narrative is formed as, together with Nga Taonga Tuku Iho o Nga Tupuna, this part of the Museum is divided into three defined sections: ‘early’ southern Māori, ‘late’ southern Māori and early colonialism. Each section seems to unfold and replace the one before.

Treasures left by our Ancestors (2016) Ana Iti

In a conversation with Bridget Reweti (Ngāti Ranginui, Ngāi Te Rangi), Iti talks about how being on an artist residency in Adelaide taught her to pay close attention to the day-to-day touristy sites of the places she happens to be, and to interrogate why they are the way they are.(2) As part of this same conversation, Iti also talks about how a lot of public information about indigenous cultural practices exists in museums (due to how indigenous cultural practices were often discouraged, maligned and/or systematically destroyed by the same societies that constructed these museums), and how in relation to Māori cultural practices, museums “seem to be so obsessed with moa hunting.”(3) The third display Iti kneels before in her film illustrates this. In this one, two men and a kurī are shown hunting two moa that are guarding a nest, and in the background above their heads you can see a mountainside enveloped in a forest fire. Off camera, a skeleton of the South Island giant moa leans over the entrance to the exhibition. Little information is given about the moa as a species other than that it was hunted by humans to extinction. Also, the reasons for moa extinction are more complicated than they appear here. Without a doubt, human hunting and habitat modification lead to extinction in the centuries after human arrival. Although, there was variation between regions and species, and other factors, such as disease and pre-human environment change, arguably played a role.(4) Since moa fossils were first dug up by Victorian scientists and declared a marvel of natural history, the moa has come to take a prominent place in how museums shape the pre-colonial past in Aotearoa; so that in this exhibition, early southern Māori are broadly referred to as moa hunters. The history of their migration, exploration and navigation that brought them here is not mentioned at all, while this dramatic, imagined display of moa hunting covers an entire wall of the exhibition space.

The three other displays that feature in Iti’s film do not emphasise moa hunting to the same degree—although, the people depicted in them are still sometimes referred to as moa hunters. Other parts and stories of this history such as mahinga kai, tool making and cave drawing are indicated, but again the complexity is lost. A wall text says how cave drawings were commonly done in charcoal and red ochre, but do not reference the overlaid and complex relationship these drawings have in relation to each other; specifically, how cave drawings reflect migrations and interconnections between different arriving peoples across time, such as Waitaha and Ngāti Māmoe.(5) Instead, cave drawing is portrayed as an ancient art form, confined to the distant past.

Iti first saw these displays when she was a kid, but it was later when she visited as an adult while doing research for another artwork that she realised the distorted historical narratives present in them.(6) It struck her how nearly all the people depicted in the displays are crouching or kneeling, and she thought about the displays of European colonial dress elsewhere in the Museum where the models stand uniformly tall and upright. The only person she could see standing up here is the man brandishing a spear in the moa hunting display. Part of her action of kneeling is to empathise with the people depicted, and to get closer to what it might feel like to kneel or crouch for such a long time.(7) In Iti’s writing that accompanied her film, she describes how the people seem passive when displayed this way:

“It was as if Māori had never been explorers who came to Aotearoa using a sophisticated system of navigation by the stars and ocean currents. That instead they passively sat while ‘The sea supplied an abundance of fish, marine mammals, shellfish and other foods’.”(8)

In a way, Iti’s action of kneeling in front of these displays returns something that is lost. A contemplative feeling, as a small piece of time and space is carved out for a kind of invisible connection to the past. She draws attention to how the past is not fixed behind glass in a corner of a museum. Rather, historical memory is alive, forming and reforming through the stories we tell ourselves—stories that are still being shaped, mutated even, by the displays and objects she kneels before. In the last line of her writing, she asks “What responsibility does the Museum have to me?” As she cannot trust its version of history. Through a simple, sustained act, her intervention considers how we imagine the past and what kind of stories and impressions are left on the museum visitors by these displays as they pause, look and then move on; and who mostly ignore Iti as she kneels among them.