When I wrote that Len Lye “is not just the unsung maverick of New Zealand art, he's the unsung maverick of modern art, period,”1 I never dreamed that he would be literally “sung,” his story told in operatic form. Opera might seem an anacrhonistic choice for Lye, whose work was so much a product of the jazz age. Nevertheless, I was thrilled to learn that this amazing man was going to be immortalised in a stage show, a veritable Gesamtkunstwerk of sound, light, song and dance.

And that is just what the stellar team of Eve de Castro-Robinson (composer), Roger Horrocks (libretto), Murray Edmond (stage director) and Uwe Grodd (artistic director and conductor) dreamed into being – a sensory feast and a ripping yarn about the “least boring person who ever existed.”2 Yet in spite of enormous amounts of talent, energy, and a genuine love of Lye exhibited by the creative team and the performers, the operatic form couldn't help but hamper the freedom of expression Lye himself was so well known for.

On opening night the signs augured well: the stage was set with a backdrop of rakish white verticals, evoking filmstrips, while a 13 piece orchestra tricked out in trilbys and cheese-cutters performed a jazzy overture. And then the singing started. Naively, I'd thought that “opera” might be a flexible term, an historical musical form ripe for reinvention. Castro-Robinson has a long and distinguished career as a contemporary composer with an experimental edge, and much of the orchestration was surprising, delightful, and fresh. But the singing was unrelentingly “operatic” with virtually no spoken interludes, which made Horrocks' libretto very difficult to decipher at times (subtitles wouldn't have gone amiss!).

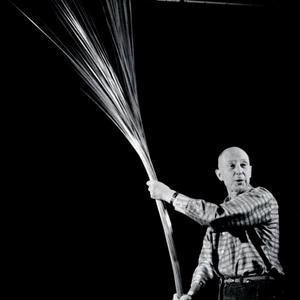

Len Lye: The Opera (2012) photo by Dean Carruthers

Lye was played by James Harrison, a likeable bald barritone in colourful getup. But in real life Lye had an unmistakably nasal, trans-Atlantic tenor drawl, nothing like the sonorous solemnity of Harrison. The first act began with Lye and his second wife Ann visiting Cape Campbell in Marlborough, where Lye lived as a boy. Daniel Sewell played an engaging young Len, scampering about the stage wielding bits of driftwood while the older Lye looked fondly on. There were some visceral awakenings: projections of rockpools merged with images from Tusalava, and footage of fish being gutted by Lye's step-father. But the simple life had unfortunate undertones: the step-father suffered a violent breakdown, and young Len and his mother were evicted from paradise. Despondent Len kicked a gasoline can, then fervently began to bash it, suddenly aware of the properties of metal, light and sound. As he did so, the bouncing ball-on-steel of his Blade sculpture faded in to view on screen.

Once the formative sturm und drang was over (a compulsory bit of NZ Gothic) the fun began. Young Lye in Wellington was hillarious, filling sketchbooks with scudding clouds while the Chorus appeared for the first time as Lye's “proper” artschool peers, undertaking “serious” art disciplines such as portraiture while dressed in frumpy smocks. Te Oti Rakena was particularly amusing as the orthodox art teacher, and reappeared throughout the opera as the “anti-Lye.” A foil to wide-eyed optimism, Rakena played the characters at the bottom line of the artworld, the money makers who keep it going with their patronage, while stifling true artistic freedom with their preconceived notions of what constitutes good work.

London in the 1920s and New York in the 1940s were both beautifully staged, with the Chorus as great dancers and fashion plates. Perhaps true to operatic convention, it was the love scenes in Lye's life that took centre stage, first with Jane in London, then Ann in New York. The art making was more peripheral, although there was a restaging of the filming of Rainbow Dance, and later, when Lye gives up film for kinetic sculpture, he plants a giant bendy Wind Wand in the audience.

Lye and Ann's visit to New Zealand took us back to the place where we began, so the opera came full circle. But there was a further scene, a kind of “stock take” which was literally exemplified by projected images of boxes and packages in Lye's studio. His life flashing before his eyes, Lye's mother and first wife, even his art teacher, returned to debate with Lye the meanings of love, life and art. With the help of the Chorus, this reached a crescendo, and images of Flip and Two Twisters pulsated on screen while percussionist John Bell shook a sheet of steel. Unfortunately, I couldn't make out what the Chorus were so passionately singing in the finale – hence the need for subtitles!

Len Lye the Opera was a rich dish – wasn't a moment of boredom, befitting its unboring subject. But there were plenty of moments where the artistic melange was perhaps a little too rich, where pulling back a notch or two might have made sense. For example, the visuals might have been productively limited to Lye's varied oeuvre. Instead of video footage of gutted fish, lighthouses, and the statue of liberty mingling with Lye's film, painting and sculpture, images of his work could have told the whole story (and wouldn't it have been delightful to run some real film loops – nothing beats the flicker of celluloid!). Lye was famously critical of what he called the “literary” by which he meant the representational in art, and narrative conventions in film. For Lye it was always about the “feeling,” yet at times Len Lye the Opera seemed a little too bound by its fidelity to the facts. And while the creative minds behind the show came from music, writing, theatrical, film and video backgrounds, there wasn't a visual artist in the core group. I wonder how that might have changed things?

The team that put this epic together must be thoroughly commended for their hard work, and for the ambition of their vision. It's an important story that must be told, and, with the impending 2015 opening of the Len Lye Centre in New Plymouth, this is surely just the beginning of many tributes. How would Lye tell his own story, if the artist who was so famously “ahead of his time” were alive today? Len Lye the Graphic Novel? Len Lye the Twitter Feed? Len Lye the MMORPG? The possibilities are endless...