Moving image, lots of moving image, is often considered the scourge of biennales. I prefer to see the siren song of video less as an incredible drain on time-hungry, foot-weary visits, more as offering the opportunity to get sucked into and immersed within a work, a projection, a screen, halting that inevitable glide by or quickly once over that other media often seems to fall victim to. A recent visit to a few biennales tested this idealism, but I come back to the CIRCUIT blog with accounts of a few moving image standouts, each of which use the medium's mode of address to call its audience into a particular dialogue or action.

As a future case study in the intersection of art and lived experience, you can't get much more problematic/interesting that the 13th Istanbul Biennale: Mom, Am I Barbarian? (14 September-10 November 2013). Conceptualised and planned around the possibilities for collective action in public space, the biennale was trumped by the very action it dared to dream of. The Gezi park protests turned curatorial premise into stark reality, while inadvertently suggesting that constructs like biennales are perhaps not required to spark such action. While expressing solidarity with the protests, the biennale could simply not operate as planned. It shrunk away from the public realm into gallery space, and very carefully worked through its connections to the freshly disputed systems of capital and power.

All of this provides the perfect context for Turkish artist Halil Altindere's Wonderland (2013) with its raw protest and expression of unsuppressed anger at the political system and decision makers in Istanbul. While many of the works in the biennale were either reshaped by or consciously followed the unrest (a good example here being Danish artists Elmgreen and Dragset extending their project of having subjects write journal entries within exhibition space to include young men recalling their role in the Gezi park protests), Wonderland was made in the months leading up to these events, serving as a precursor to rather than a document of the growing dissatisfaction soon to erupt into decisive action.

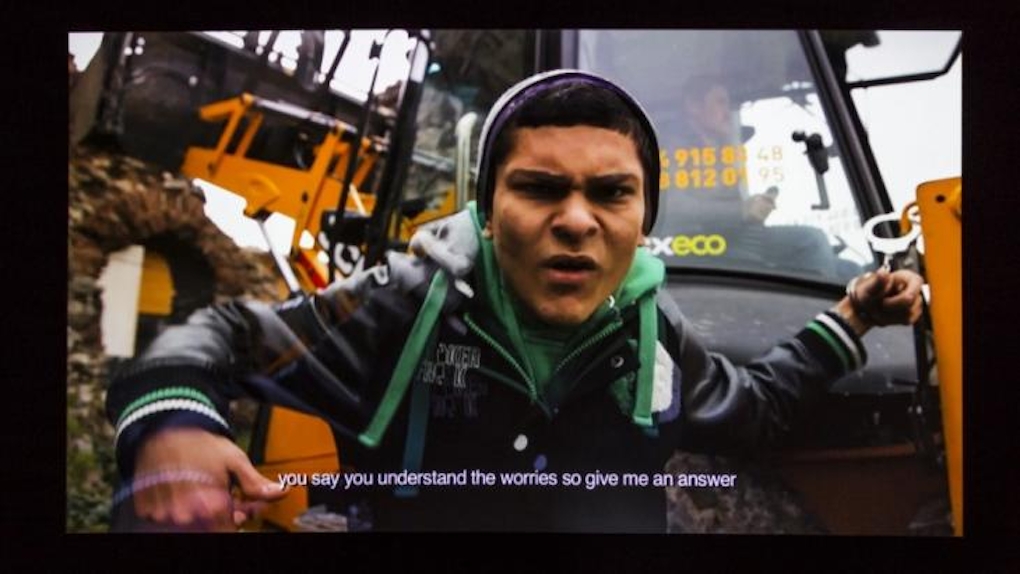

Still from Wonderland (2013) Halil Altindere

"By far the most talked about work in the biennale, Wonderland serves these needs, offering a kind of political-exoticism—even of course if its sense of real engagement is offered up within the controlled, safe and sanitised throw of the projection, the black box, the biennale."

Using the format of the music video as he has previously co-opted other signs and symbols of power, Altindere’s work captures local rappers Tahribad-ı İsyan railing against the destruction of the Sulukale district, historically home to Istanbul’s Roma communities. The rappers lament "the downfall of the city" and set about disrupting its subsequent gentrification. They sing of "pissing on the foundations" of newly erected apartment buildings, and are shown destroying machinery, reclaiming areas now deemed as off limits, beating and setting a security guard on fire (another work by Altindere in the biennale literally cuts a security guard down to size, presenting a mini-me sculptural version patrolling the entrance to a gallery space but in no way in control of this environment), before finally surviving being shot by police.

Wonderland explodes from its constructed room with a pretty nasty case of sound spill which here actually works to the benefit of all—spreading the videos infectious call to action through the entire gallery space at Antrepo, and exuding an energy, power and relevance that the biennale desperately needs. Wonderland's call for defiant artistic action in the face of corrupt power systems connected with what seemed at first like an odd selection in the biennale—a restaging of Guillaume Bijl's SUSPECT of 1980, a recreation of the artist's studio following a police search based on a neighbour's claim of suspicious activity.

While a standout and powerful work, the attention Wonderland is receiving clearly speaks to something else, to the audience's need or desire to feel a direct connection to the recent events and the sense of urgency and relevance of the situation still palpable outside those gallery walls. By far the most talked about work in the biennale, Wonderland serves these needs, offering a kind of political-exoticism—even of course if its sense of real engagement is offered up within the controlled, safe and sanitised throw of the projection, the black box, the biennale.

Meanwhile, representing Slovenia at the 2013 Venice Biennale (1 June-24 November 2013), Jasmina Cibic's For Our Economy and Culture comes at systems of power and representation in the best ‘biting the hand that feeds kind of way. Ushering the audience into the exhibition space via a window display of traditional oil paintings later revealed to be part of the National Parliamentary Collection, Cibic presents a pair of videos dramatising a parliamentary committee debate around an artwork entitled The Fruits of Our Land. The artistic merits of the work are discussed, but the debate really centres around its ability to represent the nation within the newly build People’s Assembly.

Still from The Fruits of Our Land (2013) Jasmina Cibic

The quick piling up of conflicting personal and political interests as the discussion endlessly circles around itself (beautifully incorporated into the looping of the videos) is hilarious, disquieting, and all too familiar. In this context, Cibic manages to both revel in and critique the very processes of national representation that lead to her work playing right here and right now, implicating all in its wake. Yet its reach is far broader. The work taps into wider patterns of culture making and control that extend well beyond this context and, as the historical reconstruction emphasises, across time and place. Seeing this work in the days leading up to New Zealand’s announcement of its 2015 Venice representative provided another layer of intrigue, and one of course has full faith that the discussion around that table was of a more robust nature than that represented here.

The oddity and complexity of Cibic’s work ramps up with the growing realisation that this discussion is in fact lifted from archival records, specifically a recorded transcript from one of the protagonists family’s archive. Neither the self-interested art historian (continually insisting that his objection to the committee decision be noted) nor the clock watching politicians (determined that a decision must be reached, and the President informed immediately) cover themselves in glory, but it is the state architect Vinko Glanz who takes the brunt of Cibic’s satire, especially for his insistence that the work and art and artists in general must submit to architecture. Glanz’s philosophy is utterly reversed in the exhibition’s artistic transformation of a domestic architectural space into a public space to house these discussions around the merits and politics of cultural representation. As a final subversive touch, this space is decorated with wallpaper featuring the Slovene beetle, a failed national icon named after Hitler.

The Lyon Biennale (12 September 2013-5 January 2014) includes an old favourite—Shanghai-based collective Madein Company’s Physique of Consciousness, a centerpiece of the City Gallery Wellington/Circuit exhibition .

The self-proclaimed "first cultural fitness exercise ever made" surprisingly does not appear in moving image form at all in Lyon. Rather it has been transformed into its own museum, a static glass case based display. Each case includes an image of the instructor frozen mid-movement, surrounded with an abundance of found photographs and explanatory texts that bring together various sources and usages of this gesture or movement from across cultures, history and belief systems. There is a particularly strong emphasis on contemporary and celebrity culture’s misuse and misunderstanding of hand signs thrown and looks given.

Still from Physique of Consciousness Museum (2011-13) Madein Company

This turn to museological methods and negation of the moving image both changes the original work and reverses those standard biennale efforts to break down or out of traditional gallery spaces and models (Lyon has artists breaking through walls, painting on the outside of the gallery etc). Such structural disruptions characterise MadeIn’s practice, and especially that of its founder Xu Zhen, who, in 2009 after all, gave up his individual artistic agency to form this "cultural company." Here the museum's mode of difference and resistance seems to signal a desire to shift or direct the readings of this very well travelled work, especially within the formats of the international group show or biennale that it has regularly appeared in over the last few years as representative of "contemporary Chinese art" when in fact it’s largely concerned with disrupting such easy forms of cultural reading and packaging.

Where the video amasses a series of found movements into seamless action, the museum isolates and locates each movement within a complex system of signs and a contested history that often moves between good and evil, past and present, East and West. Reversing standard museum practice where video is often called on to elucidate or somehow bring static objects "to life", here traditional display mechanisms of the glass case, the mount and the explanatory label are used to upset easy readings of the video, turning its apparent call for participation in collective cultural exercise into a more complex and troublesome proposition than may initially appear. The Museum takes the video’s invitation to participate and attaches a warning label—no gesture is neutral, proceed at your own risk. This ends up serving as a pretty good disclaimer for the works of Halil Altindere and Jasmina Cubic, as well as Madein Company.