It hasn’t always been easy to see shows in Tāmaki Makaurau lately. With COVID postponing exhibitions, openings and cancelling flights (nevermind the extended impact on artistic production) the expectation of seeing art in the city has been tempered by a certain pessimism about whether the doors would actually be open. A recent 24 hour sojourn in the city coincided with the opening of two new shows around K Rd, and several ongoing installations about town, all of which presented works by artists deeply ensconced in the moving image. With the possibility of another lockdown never far away, the weekend presented itself as an opportunity to grab some fast takes on shows about town. Have Uber, will travel.

At Artspace, Natasha Matila-Smith (Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Hine, Samoan, Pākehā) opened her first solo show, I think you like me but I’ve been wrong about these things before. At the entrance, dangling translucent curtains usher you into a twilight interior, blanketed by a warm sonic hum. One can almost imagine Matila-Smith tapping the F1 key on her mac laptop, diminishing the back-lit luminescence of Artspace to a warm throb. Working with text, photography, video and a giant heart-shaped bed nursing an open computer, the show ostensibly presents as a diaristic record of solitude and longing. At the same time, a series of large photographic selfies reveal Matila-Smith the flirt, coyly revealing glimpses of her body, the edge of a stocking, the lift of a skirt. If a large wall text says "MY HEART HURTS SOMEONE PLEASE FIX ME", here in these photos Matila-Smith clearly knows that someone is always watching. In the end, she wants your attention, not your pity.

Over the road at the Audio Foundation, Jamie Berry opened Whakapapa Algorithms with a live A/V performance that prompted an extraordinary sustained applause from the AF’s basement audience. Berry’s work draws on home video and photography of family, current and past, but stretches beyond the history of photo-chemical reproduction with the addition of a score drawn from the mapping of her DNA. Berry’s images are constantly in motion; the combination of naturalistic imagery with abstraction almost suggests her as Aotearoa’s most natural contemporary heir to Len Lye. Berry’s soundtrack combines a pulsing electronic repetition (reminiscent of Australian jazz trio The Necks) with the swooning sound of native birds and waiata. Images of family move in, out and within the frame. If Matila-Smith is searching for love, in Berry’s work, it is unconditional; if Len Lye famously sought "Individual Happiness Now", Berry presents a Māori worldview of collective wellbeing, existing on a past, present and future continuum.

Jamie Berry, Live Performance excerpt, Whakapapa Algorithms (2021), The Audio Foundation

At Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery, whakapapa is again a connective theme, in Steve Carr and Christian Lamont’s acute meditation on loss, Fading to the Sky. The centrepiece is a series of 23 iPhone photographs of Carr shot the day after his mother’s passing. Taken by the artist’s wife, and drawing on Carrs’ long-standing interest in the sequence, they show the artist’s dimly lit head and shoulders, both facing and turning from the camera, sometimes nursing an apple with his chin. In the corner of the room sits Lamont’s two monitor sculpture, lying on the floor like a figure poleaxed by grief. Fluctuating with indistinct purple, blue and white light, Lamont’s work suggests something ungraspable and intangible. Likewise, screening on the opposite wall, Carr’s video Winter Feeding (2016) presents a rotating image of a slab of beef lard devoured by unseen prey, leaving a devastated organic structure.

-Steve-Carr-and-Christian-Lamont-Te-Uru_CIRCUIT.jpg)

Installation view of Fading to the sky (2021) Steve Carr and Christian Lamont, Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery (2021)

There are further ambient touches from Lamont; a side window glowing in methylated purple through blinds, and lights under the floor projecting a soft hum of yellow. This is new territory for Carr, working collaboratively with one of his students, and allowing vulnerability to come to the fore. One last work is a puzzling addition and perhaps hints at a lingering wariness of personal revelation; the video American Night (2014). For 15 minutes a solitary bird waits on a branch as dawn breaks and fades. Mostly silent, the video is interrupted briefly by the furious chirping of the bird, breaking from a stoned mechanical slumber to herald the near dawn. In the context of Fading to the Sky it’s tempting to read the bird as emblematic of Carr themself, or perhaps some sort of sentinel, but already the room is a tight knot; American Night is possibly an unnecessary embellishment to a moving portrait of grief.

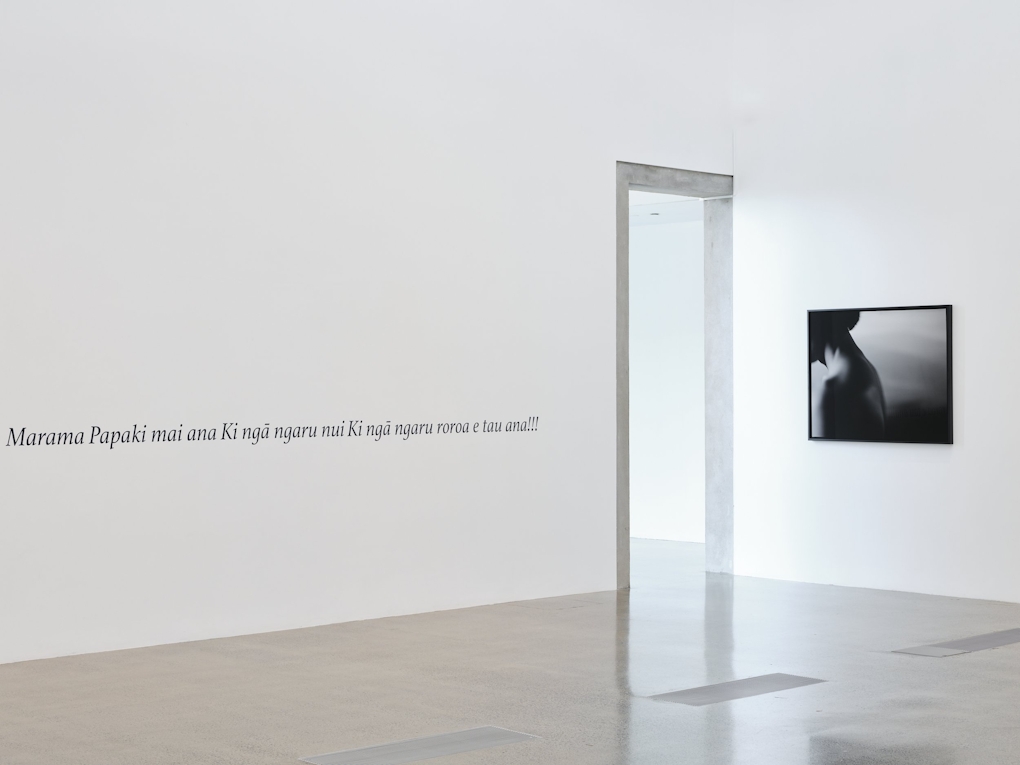

Walking amongst Te Uru’s hallways, I heard the sound of a mournful waita drifting from Shannon Te Ao’s (Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Wairangi, Te Pāpaka-a-Māui) Karere ana, Taapapa ana. Shot in black and white, the video occupies one of two rooms in the larger project Ka mua, ka muri. In the second room, a sequence of stills shows what appears to be a child moving at speed through mid air. On two walls, a single line of text.

Just as Carr chose to collaborate with Lamont, Te Ao has worked with composer, weaver and orator Kurt Komene (Te Ātiawa, Taranaki Whānui) to compose two waiata; Karere ana and Taapapa ana. Where Carr and Lamont ostensibly present discrete works side by side, Te Ao’s collaboration with Komene employs a number of slippages and exchanges with time, language and material. In the video, two youths drive away (we’re told by the wall text) from the scene of a tragedy. The car and its' passengers move in an atmosphere of languid mourning; time processed by grief. The video alternates between singing and silence, and it is over the silence that Te Ao presents text, though not necessarily that of the onscreen waiata.

-Shannon-Te-Ao.jpg)

Still from Karere ana, Taapapa ana (2021) Shannon Te Ao

Perhaps you could read this as a deft filmic device; instead of undercutting the image and the weight of the moment with subtitles, Te Ao draws us into the purity of the song and the weight of the moment. Given that the work was commissioned by a Canadian institution this would also be an interesting response to being asked to present a work drawn from te ao Māori in an international context—a refusal perhaps, to so readily translate Indigenous experience so directly for the global art audience. But in room two, the personal dimension of Ka mua, ka muri hits home and hits hard; the sequenced image of the youth an incomplete record, the trajectory of the action sequence moving beyond the speed of the shutter. Like Lamont’s abstraction, and Carr’s judicious inclusion of Winter Feeding, Te Ao lets us feel the pang of grief but not the impact.

Installation view of Ka mua, ka muri (2020) Shannon Te Ao, Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery (2021)

Translation has been on Ana Iti’s (Te Rarawa) mind a lot recently, as evidenced in her CIRCUIT commission Howling out from a safe distance (2020), and at Te Uru, in her recent video How should we talk to one another? Where Howling out... isolates words from a nineteenth-century te reo Māori newspaper, here she isolates sentences from three twentieth-century New Zealand novels. The video is a series of slides, each showing a line of black text sitting atop the bleached white of the photocopy. At the edges, Iti’s thumbs hold the pages open. Like Matila-Smith, Iti gauges the weight of text, sieving out verbs and nouns in highlighter yellow: words like path, waiting, research. Sentences leap out, some benign, some awkwardly hinting at some drama off the page. However, the title suggests that this is less a mystery of who is speaking and to whom, but a question of how to resolve our differences.

-Ana-Iti_CIRCUIT.jpg)

Still from How should we talk to one another? (2020) Ana Iti

Across town at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, both Iti and Te Ao are part of art Toi Tū Toi Ora, the sprawling survey of contemporary Māori art curated by Nigel Borrell. Featuring 130 works, the show occupies the entirety of the gallery, and embodies three stages of the Māori creation story across it’s three floors. The show is a magnificent achievement seeking to tell a vast story, and at the opening, curator Nigel Borrell spoke of his regret at having to exclude so many artists from the show. In this compact space, some moving works manage to achieve a sculptural presence (notably Lisa Reihana’s (Ngāpuhi, Ngati Hine, Ngāi Tu) Ihi (2020)) while others feel less like installations than thumbnails from the catalogue that surely must follow.

-Lisa-Reihana,-Auckland-Art-Gallery-Toi-o-Tamaki,-2020.-Commissioned-by-Regional-Facilities-Auckland,-and-displayed-in-the-Aotea-Centre-in-Tamaki-Makaurau-Auckland-Aotearoa-New-Zealand.jpg)

Installation view of Ihi (2020) Lisa Reihana, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2020. Commissioned by Regional Facilities Auckland, and displayed in the Aotea Centre in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand

Nova Paul's (Ngāpuhi) classic 2010 film This is not dying is announced through the soft click-clack of the 16mm projector which leads you upstairs, to where it is installed in a kind of landing space, the image beamed on to the end wall. Like Berry, Paul’s work is a joyous celebration of whakapapa, whānau and whenua, and this surely is the triumph of Toi Tū, Toi Ora, but in this installation context, the image itself struggles for definition. This is a shame, especially when the title could also be read as allusion to Paul’s beloved mediums of analogue film and cinema.

Time is an issue for this show, too. On the way out I meet an artist returning for their third visit, having recently discovered they’d missed a whole section of the show. How can it be that a show of Toi Tu Toi Ora’s scope and significance will only run for six months? And surely, in a COVID year interrupted by lockdowns, couldn’t the gallery extend the show to allow audiences greater opportunity to absorb its many offerings?

Tāmaki Makaurau, it’s been a blast, but alas, my 24 hours is up.