How might the video essay be employed to practise historiography? Can artistic practice take a critical stance on the writing of history? In three recent video works, 1991 (2016), Cold Storage (2017), and Youth Portrait (2022), I would argue that Tāmaki Makaurau-based artist Tim Wagg is enacting an idiosyncratic form of historiography, and that his practice does so using a range of methods. Throughout these three works, there is an emphasis on historical interpretations and representations of the past and recent past.(1) Here I take Brisbane-based art historian Chari Larsson’s summary of the term historiography as "the writing of history as opposed to history itself."(2) Within his chosen medium, Wagg writes histories of ambience, utterance, recollections, archives, caricature, interiors, built environments, public and private infrastructures, landscapes, plants, and machines.

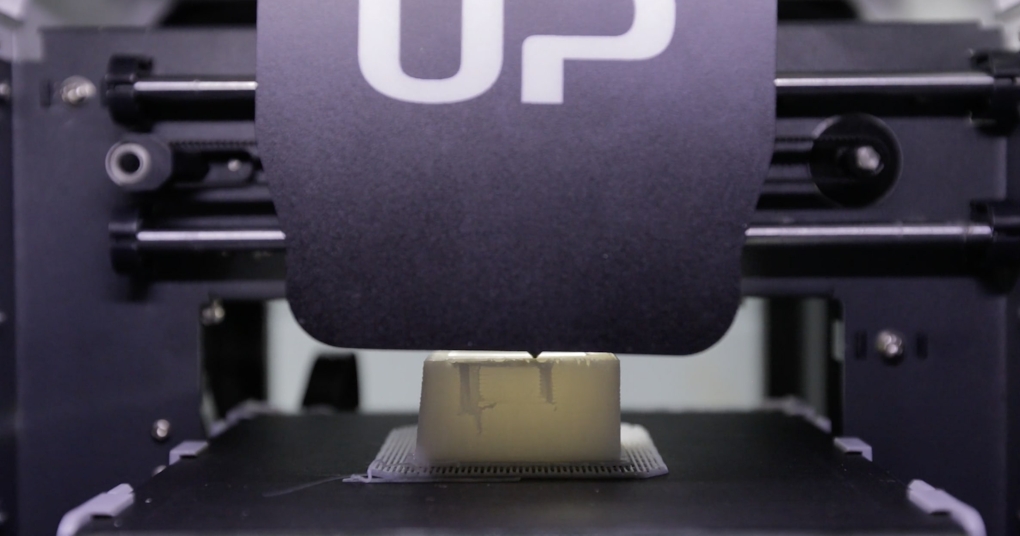

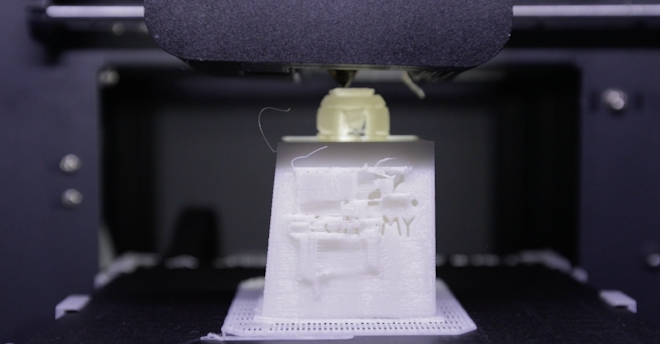

The familiar whirring of a small internal fan starting up. A consumer model 3D printer illuminates and springs to life, beeping and clicking. The machine adjusts and sets itself up to execute the task it has been given. The hotbed is raised to the desired position and a small nozzle moves back and forth, swiftly ejecting liquid resin. For the most part, 1991 documents a process of 3D printing, from beginning to end. Yet just as the additive manufacturing process of creating a physical object from a digital design involves the building up an object, layer by layer, Wagg carefully assembles and deftly intercuts footage of a domestic interior, a suburban garden, and an industrial environment. Each of these locations has its own affect and political dimensions.

Tim Wagg, 1991 (2016)

... as a young person you can’t even begin to imagine what it was like...

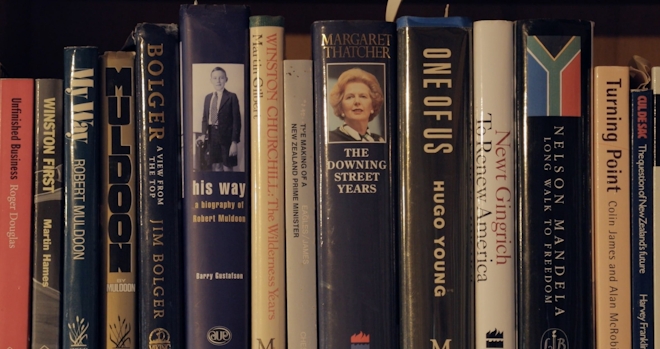

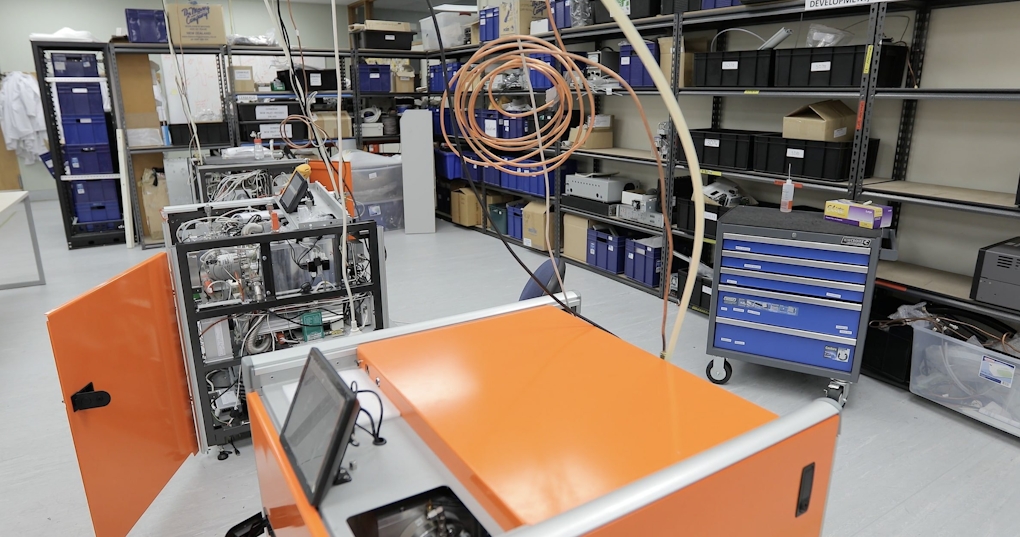

The soundtrack of 1991 is composed of a voice-over and electronic music made up of pulsing, prolonged synthetic tones and semi-industrial beats. An older woman begins to give an account in the first person: "I had the most quintessential NZ upbringing, I came from a farming family, my parents were community and political activists, hence my political gene. I’m a radical, I’m a natural disruptor." The narrator is Ruth Richardson, a politician who served as Minister for Finance from 1990 to 1993, in the fourth National government. Interspersed with the footage of 3D printing are locked-off and fluid tracking shots of the inside of her home, a well-clipped, wintry garden, and a biotechnology facility she is affiliated with. Though Richardson herself never appears in the video, a kind of portrait forms through the clips of her voice and her domestic environment—we see a home gym complete with a Tour de France stationary exercise bike, a personal library with shelves of books relating to neoliberal politicians from around the Western world, policy magazines, and a copy of her infamous 1991 budget.

Tim Wagg, 1991 (2016)

Tim Wagg, 1991 (2016)

the real champion was the idea, the idea of a liberated economy, a liberated society, personal choices, what a market economy really looked like.

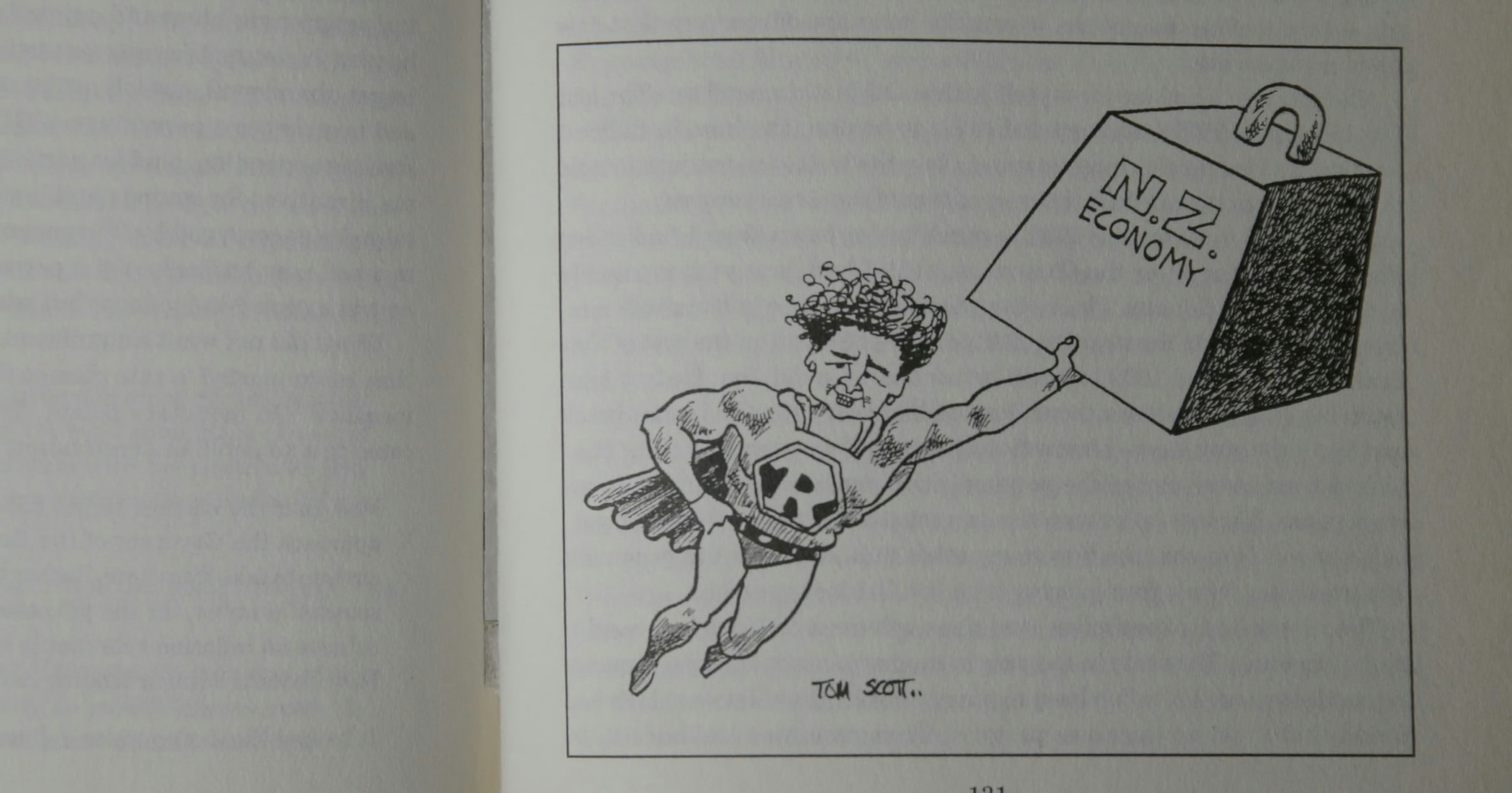

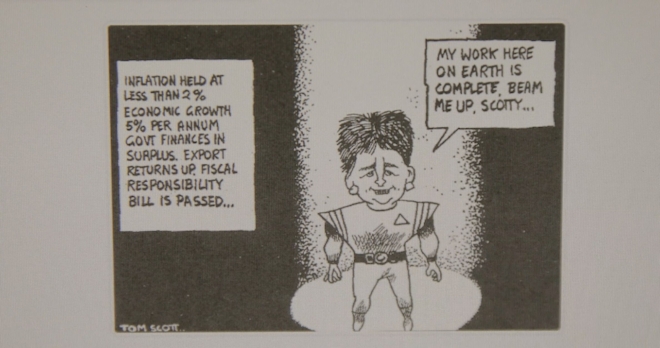

Upon the timber-clad walls is a chart from the Reserve Bank that tracks the first twenty years of the New Zealand dollar float, as well as a framed original drawing of a political cartoon by Tom Scott. In the illustration, Richardson is depicted as a character from a science fiction series. She stands in a beam of light; the caption reads: "INFLATION HELD AT LESS THAN 2% ECONOMIC GROWTH 5% PER ANNUM. GOVT FINANCES IN SURPLUS. EXPORT RETURNS UP. FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY BILL IS PASSED..." A speech bubble beside Richardson states, "My work here on Earth is complete. Beam me up Scotty." In another cartoon, Richardson is portrayed as a superhero, complete with a cape, fitted suit and bulging muscles. Flying through the sky, she effortlessly holds a massive weight emblazoned with the words 'N.Z. Economy.'

Tim Wagg, 1991 (2016)

...that settled social contract was around, you know, abundant public funding of health and education and welfare and a view that, you know, strategic assets ought to be held by the state, coming along and disrupting that was, you know, no easy feat...

This metaphor for the economy of Aotearoa New Zealand as an onerous weight is taken by Wagg and transformed once again; it is this cartoony form that is being manufactured by the 3D printer. In turn, Wagg mailed this very object to Richardson, as part of his request for her participation in the project. As a kind of talisman, the object then forms a crucial role in the activation of an alternative economy—that of the gift—and one that brings about reciprocal exchange.(3) Wagg’s construction of an object that stands in for a nation state’s economy harks back to Michael Stevenson’s earlier work The Fountain of Prosperity (Answers to Some Questions About Bananas) (2006). With this sculpture, Stevenson created a replica of the MONIAC, a hydraulic proto-computer created by economist Bill Phillips in 1949 in which adjustable pipes and containers direct flows of water to illustrate the flows of capital in and out of a national economy.(4) Indeed, in art-historical terms, Wagg’s research-led practice and critique of late capitalism has much in common with that of Stevenson, though Wagg has focused on lens-based practices where Stevenson generally uses installation.

Tim Wagg, 1991 (2016)

Tim Wagg, 1991 (2016)

Taken together, the removed and clinical shooting style of 1991, its electronic soundtrack, 3D printing footage, and scenes of the biotech facility create a feeling of techno-optimism. This is a sentiment shared by Richardson, who intones "for me, the real celebration that the technology has bought is the choice and preferences of individuals, you know that’s where ultimately decision-making lies and where there is the ability then to use that technology to create whatever community suits you best, it transcends boundaries, it transcends barriers." This technophilia is contrasted with Richardson’s fusty, middle-class surroundings. Amongst cold clods of soil are African violets and recently pruned shrubs. The trees are bare. The property owner has filled her home with artefacts from her travels; she is well settled. There is a ZZ plant, a vase of peacock feathers, artworks from indigenous cultures of Te Moana nui a Kiwa. Throughout the video, there is a pull of fascination from without as well as the suspicion that Wagg sees this home and garden as very much belonging to a previous generation, with all the attendant power and privilege. Perhaps that of his parents.

In each of his recent video works, Wagg sets up an oscillation between biography and autobiography. 1991 is, in fact, the year of the artist’s birth. It is also the year of the birth of Richardson’s 'baby,' what has since been referred to as the "Mother of all Budgets"—a copy of which is captured in Wagg’s video.(5) In one sense, he is interested in portraiture, but there is an ambiguity as to what the subjects of these portraits are. Is it Richardson? Contemporary Aotearoa New Zealand? The current economic climate? 1991 recalls, for me, a quotation taken from Karl Marx: "Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please in circumstances they choose for themselves; rather they make it in present circumstances, given and inherited."(6) Across 1991, I get the impression that Wagg is trying to paint a picture of the historical circumstances into which he was born, and to begin to investigate exactly how things became the way they are now. It’s a kind of portraiture without a face. Returning to statements by Larsson, she posits the intriguing provocation "that perhaps every discourse is autobiography."(7)

Tim Wagg, 1991 (2016)

Wagg’s 2017 video Cold Storage is made up of interior and exterior shots of analogue and digital archive facilities. The work unfolds as a sort of virtual tour, beginning at the National Library of New Zealand, and continuing through that organisation’s move of its digital repository, the National Digital Heritage Archive, to its new home at the Revera data storage facility in Trentham, Upper Hutt.(8) These two locations act as the setting for an exploration of the purported safety of "the social, cultural history" of Aotearoa New Zealand, stored as data in cloud computing infrastructure. The accompanying soundtrack is made up of 'weightless' music, a sub-genre of ambient electronic music designed to resemble "spatially untethered club trax."(9) This time, a young man (not the artist) provides the spoken narration, which explains the process of migration of cultural material from one place to another, and the issues regarding its ongoing maintenance and safekeeping. This text is an amalgamation of two interviews, one with a staff member from the National Library and the other with a facilities manager at the Revera data centre. Extracts from these two interviews were combined with fragments of text taken from documents regarding the archive’s move.

Tim Wagg, Cold Storage (2017)

Cold Storage has a binary structure: it is a two-channel video and was shot in two locations. Within the work, Wagg uses digital footage to capture the unique built environments of the two storage spaces. One is the brutalist 1970s building that houses the National Library of New Zealand; Wagg’s camera captures its carpeted rooms, low ceilings, steel shelves, and colourful murals. The old server room with its linoleum tiled floors and cream-coloured walls. Occasionally, objects and various bits of equipment are scattered around in a haphazard manner. Monitors and computer components lie around, discarded, and visible wires and cables spill out messily. It is an untidy space that looks as though it has been evacuated in a hurry. There is an overwhelming sensation of quaint earnestness, obsolescence—a kind of hapless vulnerability. As Sydney-based collective Snack Syndicate has written, "the complexity of archives is that they are simultaneously sites of preservation and destruction, sites of judgement and expressions of power."(10) Bearing this in mind, the old server room is an expression of the disempowerment that comes with a lack of resources. The accompanying voice-over describes the constant threat of the archive’s destruction, whether it be by flooding, fire, earthquakes, neglect, or even wilful sabotage. The very transfer of digital material from one place to another seems tenuous, at the whim of government grants and access to funding and resources.

In contrast, the privately-owned Revera facility is a visual expression of power. It resembles a military compound or an industrial warehouse; it is made of cinder blocks and is surrounded by a perimeter fence, security cameras, and floodlights. Its architecture is non-descript and functional; there are long, narrow, white-walled corridors and concrete floors. Devoid of ornamentation, its only features are its exposed utilities—venting, fans, gas tanks, safety signs, and accoutrements relating to emergencies. These interiors are orderly and precise, rows of racks, modules and servers are contained in cages in perfectly straight rows within gridded, labelled configurations. Cold Storage images a fascination with the very apparatus used to preserve and maintain the National Digital Heritage Archive. About two-thirds of the way through the work, Wagg lets the weightless music take over; it’s as if the artist gets lost in the brute matter of his surroundings, the repeated forms, the secure, industrial environment, and contents himself with editing the moving shots in time with the rhythmic beats.

Tim Wagg, Cold Storage (2017)

Tim Wagg, Cold Storage (2017)

At the core of Cold Storage is what anthropologist and historian Ann Laura Stoler has called "the epistemic anxiety of the archive," that is, "the tension between its performative authority and inherent fallibility."(11) The Revera facility, as a private infrastructure provider of cloud services to the New Zealand government, performs its authority and security. However, Wagg’s narrator dwells on the risks involved and how these are mitigated through location, design, physical restraints, and the precautions taken in the event of a fire or loss of power from the national grid.

The archive, then is always radically unstable; its perceived wholeness and authority is derived from what is exterior to it, and, as such, it can only be properly understood in relation to that which it simultaneously excludes.

Any "perceived wholeness and authority" of this nation’s archive is thereby derived from the impressive exterior of the Revera facility, behind its sharp security fences and surrounding pine plantations. Wagg’s fascination with the apparatus preserving and storing the archive is captured by technophilic shots of rows and rows of small green and blue lights busily flashing on and off amidst the inky black backgrounds provided by the electronic hardware. Yet Wagg undermines the so-called wholeness and authority, when, 14 minutes into the video, footage of the Revera facility begins to visually deteriorate and pixelate, so that the old server room at the National Library appears to infiltrate it. The corridors of cold, orderly steel lockers almost melt into chaotic patches of black and grey, then morph back into the dirty-cream beige walls of the old archive rooms. Wagg used a technique called 'datamoshing' to corrupt the footage. This process involves removing key frames through a complicated sequence of exports, so that these frames then have more information than others. In keeping the original sequence, the surrounding footage becomes untethered—only some information gets through—so that the end result looks as though spaces are falling into each other. Datamoshing allowed Wagg to blend the two locations together, with an effect that resembles what the narrator’s calls "bit-rot and bit-flip," one of the dangers that digital archives are prey to.

Tim Wagg, Cold Storage (2017)

Wagg’s choice of subject matter in Cold Storage is telling; he dwells on a kind of micro-moment in the history of Aotearoa New Zealand – another interesting historiographic position. He addresses one moment in history together with its shifts or pivots: archiving the move from analogue to digital, from an imperious building in our nation’s capital opposite the Parliament buildings to a non-descript facility in the greater city region, and from a completely public facility to a mixed public-private partnership. There is little value judgement given, there is no "tone of certainty." Perhaps instead, Cold Storage demonstrates what French theorist Georges Didi-Huberman has called "the uncertainty of not-knowledge."(12) Across the work, there is an "unsureness" "as to the nature of representation in art" – an equivocation, a partiality. Cold Storage does not offer any answers and its overall argument or thrust is deliberately far from comprehensive or persuasive. Wagg is content for it to remain equivocal and partial, though when considered in tandem with 1991, the under-resourcing of the national archive and its subsequent reliance on private infrastructures could be considered direct outcomes of Richardson’s reforms.

Tim Wagg, Youth Portrait (2022)

Wagg’s most recent work, Youth Portrait (2022), comprises footage of the city of Tāmaki Makaurau: its harbour, vistas of the cityscape as seen from a moving car, unfurling highways, houses, suburbs, cliff-top mansions, housing developments and construction. The familiar, distant cone of Rangitoto upon the sea. Shot on digital video, in 4K at 60 frames per second, everything has a heightened look, every second of footage literally holds too much information. In this work, Wagg’s protagonist is Jadyn Dixon, a young realtor from the North Shore.(13) He is captured unlocking the office door at the start of the day, driving his car, standing on balconies and by pools, sitting on couches inside properties. There is no way to know whether any of these spaces are his home or merely ones he is selling. Youth Portrait combines a voice-over provided by Dixon, together with an accompanying soundtrack that ranges from ambient drones and synths to more energetic, upbeat electronica.

My car clock and my watch on my wrist is always fast, so that way you get there bang on time and you’re five minutes early, five minutes early is always bang on time anyway, the way I look at it.

With the title of this work, Wagg deliberately invokes the convention of an artwork that captures the likeness of its subject. So how does this involve a kind of social history? What aspects of this portrait might be biographical? There is an ambiguity as to what or who the subject actually is. How exactly do you create a portrait of the abstract noun, 'youth'? Who or what is this youth? Is it the so-called young city or country in which the work is set? Is it the market economy, initiated three decades earlier by Richardson? The most obvious contender is Dixon himself, but there is still a pervasive sense that Wagg is interested in creating a picture of his present circumstances, as they are given and inherited. Writer and art historian Lucinda Bennett has observed that "Jadyn’s individuality is sublimated into his age… this is a portrait of an individual but also a generation."(14) Bennett reluctantly uses the generational descriptor to posit that the portrait is that of a 'millennial,' before qualifying this further as one "of primarily Pākehā millennials in Aotearoa, those of us who just about remember life before the internet but not before free-market reforms of the late 80s and early 90s." If Youth Portrait is haunted by Larsson’s assertion that any discourse is really autobiography, is this a portrait of the artist as a young real-estate agent?

Tim Wagg, Youth Portrait (2022)

Tim Wagg, Youth Portrait (2022)

I just knew I wanted to be involved in something bigger than myself, prove to myself that I had the ability to do it on my own. I guess consciously I had to do that. But I think also subconsciously it was something which was kind of embedded in me from what I had seen growing up.

Staying with Larsson, as part of her research into art historiography, she explores an 'amicable' form of writing or making, one that "signals a return to the subject, albeit in a fractured and unreliable form."(15) It could be argued, then, that in the three works discussed, Wagg is attempting an amicable writing of history that is crafted by an unreliable subject/maker. There is an overwhelming feeling of fracture throughout its 20-minute duration; Youth Portrait demonstrates a frenetic editing style, with Wagg constantly moving between still and moving images to break up rhythms and interrupt the flow. Together with the relentless beats of the music, an inescapable momentum builds, as though reflecting the never-ending grind and hustle of keeping one’s head above water in late capitalism. Youth Portrait was shot with the aid of a gimbal, a tool that allowed Wagg to smoothly track Dixon moving through his environment, whether this is his Glenfield office, progressing from indoors to outdoors, or holding forth as he proceeds through a listing.

You know you reap what you sow. If you don't put in the work, don’t expect to get anything out of it, you know, nothing’s handed to you on a silver platter, but it never was growing up.

Wagg’s affinity for montage is ever-present; he intercuts between locations and uses rapid jump cuts that create a staccato effect. When Dixon speaks, Wagg has removed via editing tools all of his natural pauses and breaths, creating an abrupt and harsh effect. Dixon seems to speak continuously in endless sentences, and this heightens the flow of his dialogue, his message, his sales-pitch. In all three videos, Wagg displays what Larsson has called an "atomisation of the gaze," but this is particularly the case in Youth Portrait. There are starts and stops, a contrast between Dixon sitting still within a home and then zooming around the isthmus in a car, unrelenting beats. Together with his perpetual cutting and pasting of platitudes, anecdotes and motivational sayings, the effect is to make the whole video seem choppy and persistent, a never-ending series of shots and bluster.

that thrill of the chase and the feeling you get when you’ve actually chased and caught as well is quite exciting and in fact you can actually sit back and truly say, hey look, this is what I’ve done for myself.

Tim Wagg, Youth Portrait (2022)

Wagg employs what Didi-Huberman calls the "glimpse," in all of its ephemerality, strangeness and beauty.(16) Each of these three works is a fragment made up of fragments. According to Didi-Huberman, any usage of the fragment suggests an "evacuation of authority over the image," and as a strategy, it functions to "undermine objective and authoritative knowledge."(17) In turn, perhaps Wagg’s overarching methodology is the telling of histories through fragments, through quick glimpses. Collectively, across all three videos, Wagg demonstrates a vehement disinterest in taking up an authoritative stance in the writing of histories and a disbelief in objectivity. He is, after all, an artist making video art, and a young man coming to terms with the socio-political circumstances he has found himself within. For Didi-Huberman, "[t]he fragment is experimental, incomplete and subjective." In gathering together images of a retired politician’s house and garden, the new home of a digital archive, and a young realtor at work, Wagg enables viewers to "watch as unconsciously formed motifs appear." There are "glimpses" as well as "persistent worries" and "pressing invitations to think."(18) As an artist and a maker, Wagg assumes an amicable, partial, fractured, and imperfect position in the writing of history. A video essay or film d’essai is, after all, an essai or attempt.