"Farming was hard in those days, and it was just a bit of extra income," recalls Joyce Coleman to camera, followed by a short squeal of guitar from Black Sabbath.

Joyce is remembering hosting the Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival on their farm in 1973, in Cushla Donaldson’s 2017 film of the same name.(1) Joyce's name comes up on screen in Blackletter gothic font.

"I was just the lady in the background."

The camera shows the land that remains—scrappy manuka, scarred and boggy farm ground. And a belt of imposing, dark tall pines. There’s a spookiness, an unease from what’s been taken with which we’re familiar. Meanwhile it's the sound of Sabbath that continues to propel the film—as if they’re about to appear galloping over the hillside on horseback, burning torches in hand.

The Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival (2017). HD video still. Commissioned by Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery. Image courtesy of the artist.

These first few frames are an opening salvo, signaling that Donaldson’s approach to documentary-making will mercilessly play with, rather than play to, familiar documentary conventions. It will unpack the fabrications of storytelling and open out who gets to tell 'our' stories, and the reliability of the ways in which they are packaged as media on our screens.

In its eerie evocation of lingering settler-colonial darkness in the hinterland—not to mention the embrace of metal, cherishing working class popular spiritual rites of passage—this film points from 1973 to Donaldson’s 2021 film with Quentin Lind, Neighbourhood of Truth.

From Aotearoa New Zealand's first large outdoor festival—complete with Sabbath placing a large burning cross on the hillside behind the audience for their set—to the 'satanic panic' that was put upon the small community of Ashhurst in the Manawatū around the case of the late Detective Brent Garner in 1996.

The facts as I've been told them: In October of that year, police made their way to Garner’s burning house in Ashhurst, and what appeared to be a brutal attack on a fellow officer. Garner told them he'd dived out a window escaping an explosive blaze, after being bound and gagged, covered in petrol and tortured, with his back lacerated with crude razor cuts resembling the satanic sign of a pentagram. This followed a series of letters sent to a Palmerston North police station from someone calling themselves 'The Executioner', warning they would undertake an attack on a police officer.

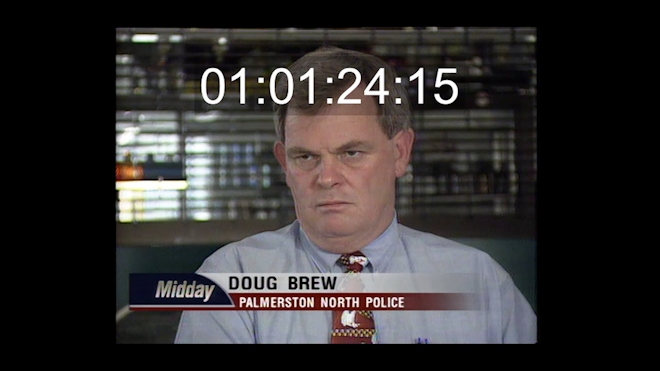

Neighbourhood of Truth (2021). Image of Doug Brew, HD video still. Commissioned by Artspace Aotearoa. Image courtesy of the artists.

While the police’s 'Operation Venus' set out to find a satanic-inspired assailant, police quietly also set up Operation Mars to investigate Garner. Two alternate truths.

2021's Neighbourhood of Truth is 26 years later. It premiered in a year that saw people convoy from the country to occupy the grounds of the country's parliament for three weeks in an incredible, sometimes frightening anti-vaccine, anti-mandate protest. Areas like the Manawatū were, it was felt, well represented. Those voices are still prominent from roadside handmade signs as you drive through.

The protests make clear how fractured and frustrated Aotearoa society can be in the face of being told of its oneness. The ugly and violent results that manifested in alternative media like Counterspin are what Donaldson and Lind's film spookily augur. With love, they're giving a more intimate open space for voices seldom heard.

Neighbourhood of Truth is a reflection that it does get weird out there. Things are spooky and unsettled. A by-product of a settler-colonial landscape and a contemporary culture that treats people as individual, identically aspirational consumers.

Neighbourhood of Truth (2021). HD video still. Commissioned by Artspace Aotearoa. Image courtesy of the artists.

Overtly rejecting slickness and a singular style of filmmaking, embracing a chaotic multiplicity of approaches—in construction, this film constantly reminds us it's representing the experiences of others beyond seamless TV news reports, TikToks and docudramas.

It ultimately asks: how artists might, in collaboration with their subjects, begin to create communities of truths? A kinder, more honest, if less resolved culture and media.

II

The Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival's interviews reveal peacefulness, diversity, and a lack of visible police presence. It's Donaldson’s song of innocence to Neighbourhood of Truth as song of experience. The pairing underlines societal changes in trust of public institutions and the rise of private commercial controls in the period in-between.

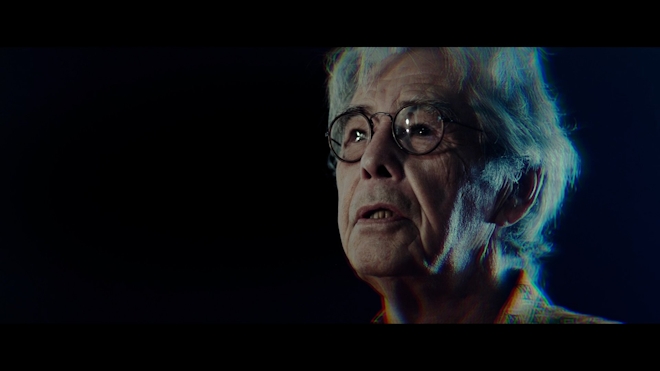

In Neighbourhood of Truth, another "lady in the background" speaks personally in a near-to-dark room (her wish for anonymity respected) of memories and experiences of the Dawn Raids, Māori land and apartheid protests, and the citizen attack on the police's 'Wanganui Computer' in the '70s and '80s. Hers is one account of an erosion of trust in police and concerns over surveillance over the period.

Neighbourhood of Truth (2021). HD video still. Commissioned by Artspace Aotearoa. Image courtesy of the artists.

We cut to film of police officers training to deal with attackers, shelves of police costumes, and soft toys for children, public military displays, care of the Linton army base (not far from Ashhurst), mixed with '50s or '60s footage of happy Ashhurst parades, floats featuring large representations of community icons, expressing a happy cultural homogeneity.

Meanwhile, excerpts of television news reports, playing up the Satanic Panic threat in the Brent Garner case are juxtaposed by memories of the feeling in the Ashhurst community at the time. The memories come from Quentin Lind's own mother Brenda Slater, who sits in Ashhurst, as captured in interview-cum-conversation with her son.

In stark contrast to the news clips, the domestic intimacy of this footage—both sharing their experiences—feels as close to an authentic neighbourly truth as a documentary might make.

Neighbourhood of Truth (2021). HD video still. Commissioned by Artspace Aotearoa. Image courtesy of the artists.

The interviewees and actors in Neighbourhood of Truth (the boundary between these roles feeling blurred) seem as much collaborators as subjects—able to derail a unitary narrative at any point. And the approaches to the appearances made by Donaldson and Lind are as disparate as their perspectives. This is no standard talking heads approach.

Juxtapositions in approach to moving image as collage creates a kind of fevered dream. As Samuel Te Kani astutely wrote of Neighbourhood of Truth in 2021, "the film stages a type of seance and resurrects a sequence of events that are weirdly relevant in this climate of gunky misinformation. It tracks like mud through a showroom."(2)

Into my head pops a very early work of Donaldson's I saw at Palmerston North's Manawatū Art Gallery in 1997 (not long after the Garner event it turns out). It was a giant bird's nest—like a relic of one of those street parades—inclusive in welcoming you to sit in it, but ominous and difficult to read in its emptiness.

Maybe this was the first of many 'Shining Cuckoo' moments for Donaldson, where, bringing diverse straws together, she lays large attractive traps of sculptures of popular consumable products in galleries (a pizza slice here, a banana split there) to weave complex ideas and mess with concepts of high cultural taste.

Cushla Donaldson, Kōkako (1997), mixed media sculpture and audio recording, Commissioned by Te Manawa Art Gallery (then Manawatū Art Gallery), exhibited at Te Manawa Art Gallery and The Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua Whanganui. Image courtesy of the artist.

III

'You wouldn’t read about it'. The old expression comes to mind when hearing the Brent Garner incident recounted for the first time (it has itself a DIY artfulness that would have appealed to Donaldson).

But, of course, today you would. And you’d watch it. We share video online in the way we once gossiped. In moving image reportage, the lines between fact and fiction, and what is true and false have become as complicated and prismatic in their subjective pictures of events as communities of oral storytelling have always been.

Neighbourhood of Truth avoids replaying the Garner story from some perceived third eye. Instead, it chooses to constantly make us question who is and isn’t getting to tell the story.

Rather than try and frame a single truth, in both Ngāruawāhia and Neighbourhood, people's experiences are allowed to bubble out as part of a more shared, or collective, universal truth, often surprising what you might expect.

Further heightening the filmmaking's sense of handmade humanity, Donaldson's films constantly show the seams of their construction, through the evidence of interviewer and camera.

Sometimes this is in visual setup. Late in The Great Ngāruawāhia, Donaldson recreates a surreal memory of young attendee, Lindy, meeting the stoned but kind-seeming young members of Black Sabbath. It's a generous counterpoint to rock 'n' roll exploitative cliches, the film clearly created in tribute to Lindy’s even younger soft memory.

The Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival (2017). Image of Lindy, HD video still. Commissioned by Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery. Image courtesy of the artist.

"As a kid you have a great sense of feeling for how people really are," Lindy reflects. "It really felt like there was this really great sense of bonhomie."

Alerting us to art's great power in playacting—creating cubbies under furniture as it were, as many of us did as children—Donaldson’s camera then leads us out of the created set (made to Lindy's memory) to show its construction in a studio. The dream is gone.

In Neighbourhood of Truth, Donaldson and Lind go further in breaking down objectivity by adding the casual and familial. Both makers appear in the film themselves as Manawatū-raised participants. All are implicated in the culture surrounding the Brent Garner affair, and it becomes clear that another key actor and collaborator Matthew Sunderland is a friend. Eventually, he reveals to us that he grew up on a farm outside Ashhurst and practised taxidermy.

Neighbourhood of Truth (2021). Image of Matthew Sunderland, HD video still. Commissioned by Artspace Aotearoa. Image courtesy of the artists.

Sunderland's role is key in destabilising the veracity of any one truth. A replacement for documentary's typical sure, authoritative, voice-over narrator. We constantly cut to him on-screen as an unreliable storyteller, recounting with relish the bizarre turn of events of the Garner case. It's as if he's remembering it as he goes, explaining to a friend over drinks. For a while there, it's hard to understand what authority he might have to be in the film, before it kicks in that that's the very point. Who are we to recount other people's stories?

To richly complicate matters further, Matthew Sunderland is likely vaguely familiar to older viewers as the actor who played unemployed gun collector David Gray in the 2006 film Out of the Blue (2006), who carried out a massacre of 13 people in the small Otago settlement of Aramoana in 1990, while policemen bravely advanced. Another '90s moment of darkness on the outskirts.

Sunderland's credentials as an actor—rather than crime authority—are underlined in the film by a short showreel of his screen roles. He, like Garner, has experience in play-acting. Sunderland recounts having an imaginary friend as a child, Peter, whom he drowns. We're all involved in re-staging our versions of the truth.

IV

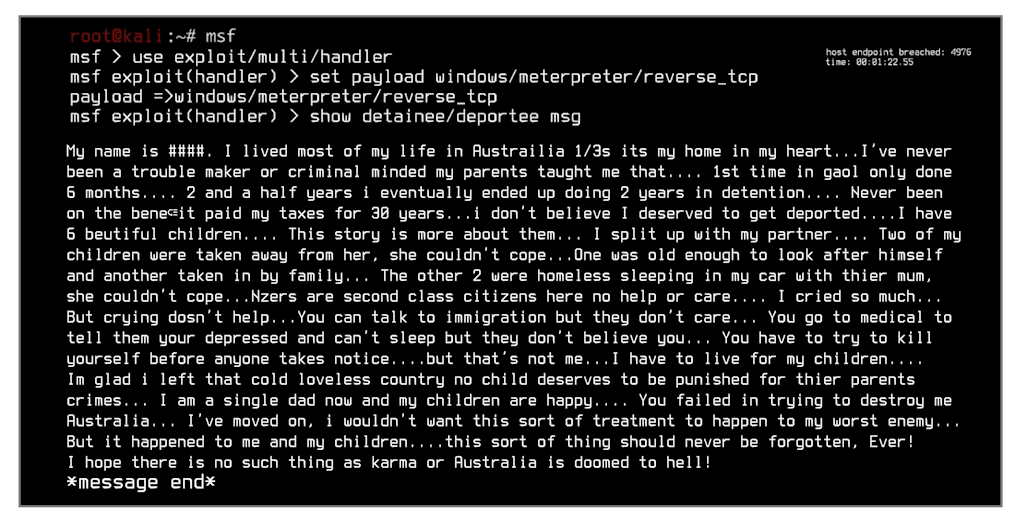

"Representation makes what was absent present again," writes David Hall in Through that which separates us, a 2020 collection of essays published by The Physics and Te Reo Kē(3). It takes Cushla Donaldson’s artwork 501s as its 'point of departure'. A work commissioned for the 2018 Melbourne Art Fair, where amongst the works for sale it gave live expression to text messages from imprisoned 501's detainees.

"A moment that is lost in time is restaged in the mind, recast as an utterance, reproduced through film, or enacted as a symbolic practice. Or a people, who were invisible to political or corporate institutions are afforded a voice, a means by which to influence the structures that control their lives."

501s (2018–ongoing). Message from person held in detention under s501. HD video still. Commissioned by The Physics Room, Ōtautahi, Aotearoa New Zealand. Installed at the Melbourne Art Fair Project Rooms. Image courtesy of the artist.

Hall's words speak to the core of the political agency of Donaldson's practice. I'd contend that Neighbourhood of Truth's key concerns aren't disinformation, fake media, or surveillance. These are tools she's concerned with, for sure, but Donaldson with Lind digs deeper into addressing the underlying action of technology of film in colonising the voices of others. Of treating people as an 'other' to that of an author and their audience.

In her practice, Donaldson experiments with different artistic strategies to disrupt the technologies of framing stories—giving voice to those constantly subjugated by political, institutional, social, and economic forces. It’s the 'neighbourhood' rather than the 'truth' at this 2021 film’s heart.

The work is ultimately about class—the inequality in representation of those not in positions of power. A working class.

Be it Black Sabbath or Dungeons and Dragons, Donaldson ennobles taste and DIY culture rarely touched by the art gallery. For once, film gives the smart talk to the underrepresented.

Neighbourhood of Truth (2021). Image of Frankie Vegas, HD video still. Commissioned by Artspace Aotearoa. Image courtesy of the artists.

"My hobbies are going to make me look terrible," chuckles Frankie Vegas, spokesperson for Satanic NZ in Neighbourhood of Truth. "I’m a true crime buff and I collect skulls! That has nothing to do with satanism whatsoever. But I do like drawing serial killers in, like, watercolours…"

Vegas is smart, delightful company, key to cutting down quickly the sensationalising of her interests. Bringing Donaldson and Lind into frame in the film in conversation with her further breaks down a subjectifciation by us the viewer. Supported, Vegas is given the floor.

Rather than focus on the actors of misrepresentation and surveillance Donaldson's focus is on those quietly taking care of others and the land.

The representation of women is naturally key to this. Opening The Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival, Joyce Coleman speaks as much for the legacy of the land and people that remain. Not interviewed in the film, as one would expect for a music doco, are the promoters, celebs who remember attending or entertainers who were on stage—in other words, the operators and actors of spectacle.

It is instead the carers. From Coleman’s interview, we move to Hugh Harawira Lynn. Perhaps best known as the manager of the band Herbs and as a rock promoter, here the focus is on security: the work of his firm Eden Security at the festival, then a key Māori and Polynesian security company, whose approach brought different cultural, rather than corporate, values to looking after people and property.

The Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival (2017). Image of Hugh Lynn, HD video still. Commissioned by Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery. Image courtesy of the artist.

The heart of Neighbourhood of Truth meanwhile could be said to live with Brenda Slater, filmmaker Lind’s mother. The fears and chuckles people daily have in their own homes in care for one another.

The 'satanic panic' that is said to have started in the United States in the 1980s, has continued to morph, most recently into the likes of QAnon. But such hysteria has, across human history, long been a tool of class, used to shame and discredit 'bad magic'—or for that matter, 'bad art'.

Neighbourhood of Truth (2021). HD video still. Commissioned by Artspace Aotearoa. Image courtesy of the artists.

It's often been a tool for subjugating women (take the witch-hunt), Indigenous people, and traditional practices connected to the land (the Tohunga Suppression Act 1907).

As Kier-La Janisse's 2021 documentary Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched: A History of Folk Horror catalogues across American, Asian, Australian, and European screen horror, the regional hinterland has long been the site of fear of supernatural forces emerging from the land, seen as an underbelly to modern urban life. A sign of our disconnection from the whenua.

Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched screened over the summer of 2023-24 at the City Gallery Wellington Te Whare Toi cinema, where Neighbourhood of Truth screened in 2022. Donaldson and Lind's film nods to the tropes of the settler-colonial Gothic in Aotearoa, but also to class issues in Aotearoa in the portrayal of an 'other'.

V

"You know the film Poltergeist where the thin hand of a woman reaches out through the TV?" Donaldson remarked to me recently, about staging performances alongside screening Neighbourhood of Truth. "I wanted that. Where you manifest."

In the use of varied media and collaboration with other artists and her subjects, Donaldson's work allows for a multiplicity of truths. It's never didactic, often playful, and not tidy to draw conclusions from.

Rather than treat an event as a defined subject, the artist allows her collaborators to open out its depiction. Each revalues their experiences and what the event meant to their wider relationships. They're not in service of anyone else's product.

Donaldson always boldly experiments with melding visual codes. She's a queen of clash, here disrupting the illusion of film as perfectly polished object. It allows us the potential to be active constructors of ideas with her.

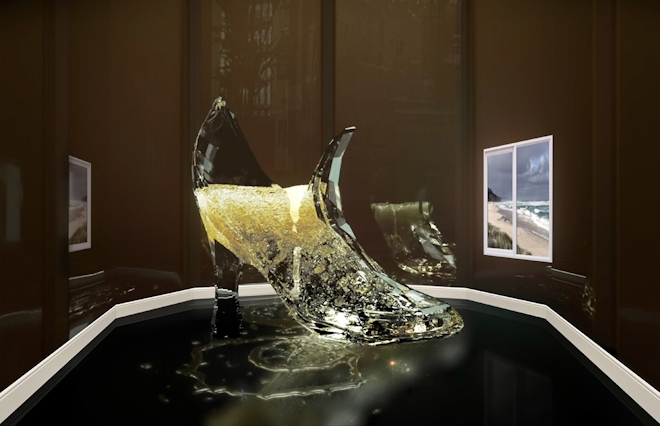

501s (2018–ongoing). HD video still. Commissioned by The Physics Room, Ōtautahi, Aotearoa New Zealand, Installed at the Melbourne Art Fair Project Rooms. Image courtesy of The Physics Room and the artist.

Witness in 501s, the interruption of an animation of champagne (or it is urine?! I always think) being poured into a giant glass slipper on a rotating showroom podium by live messages from 501 detainees.

Witness in 2019’s composite for a happiness that forgets nothing, the interruption of the dream of a show tour of the simulated glossy interior of a cruise ship by an audio interview with an Perfomance artist worker on a ship, expressing their fears at night of all that ocean beneath. We cut to diagrammatic illustration of water filling the ship's lower cavities. The filmmaking plays to the dangers of wooziness with the drug of entertainment that the boat provides with its theatres.

Cushla Donaldson, composite for a happiness that forgets nothing, part of (Un)Condition II, commissioned by The Physics Room & Suter Gallery, 2018

The fourth wall is a common theatre term—the illusion of an invisible wall separating actors from the audience. Donaldson is constantly shooting it full of holes.(4)

All of Donaldson's films mentioned here have been in arrangement with other media in exhibition in the gallery, further messing with our framing and providing connection points.

Neighbourhood of Truth was accompanied at Artspace Aotearoa and City Gallery Wellington Te Whare Toi by a performance and soundwork, tellingly titled Me and You Copy Paste by Cushla Donaldson, NYX Drone Choir, Meg Sydenham, and Matthew Sunderland.

Composite for a happiness that forgets nothing was screened on a sculpture—a giant hand, featuring QR codes to further material as tattoos.

The Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival featured in Donaldson's exhibition Fairy Falls at Te Uru featuring painting, kinetics, sculpture and—in the ultimate Westie class disruption—Donaldson appearing as part of a Sabbath tribute band she gathered on the roof for a performance of three songs.

It's been a constant in Donaldson's projects for an installation to contain multiple objects, messing with cultural hierarchies and refusing to be easily seen aesthetically as a singular set. People find this challenging. She wants you to step into the midst and connect.

Seldom comfortable but ever inviting, the multiplicity and collaborative nature of Donaldson's art opens up rare, valuable conversation critiquing how we exclude the feelings and tastes of others at our peril.

Manifesting with multiple viewing planes the spooky and kooky in everyday life, Donaldson's work is like looking at the world through a scuffed up diamond. Alluring in value and recognisable symbolism, yet complex and confusing. It refuses to follow conventions.

Yet these are our diverse neighbourhoods made navigable; the gallery rarely simultaneously so artful yet so real and revealed.