PALeo Neo Video - Chapters from the history of video art in New Zealand 1970-1990s was a 1999 survey of New Zealand Video Art installed at the New Zealand Film Archive (now Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision) and various inner city locations in Wellington. Curated by Lawrence McDonald, the show presented pioneer figures and analogue works from the 1970s (PALeo) alongside contemporary work from the emergent digital era of the 1990s (Neo). Building on a previous survey of single channel work also curated by McDonald, VDU: Video Down Under – Recent Video Art from New Zealand (1995), PALeo Neo's remit was more expansive, attempting to articulate a relationship between the moving image and other fields such as sculpture, performance and sound.

Despite the show featuring 19 artists and a landmark attempt to articulate a history of this area of practice in New Zealand, no publication was produced, photographic documentation was almost non-existent, and today the presence of PALeo Neo in any historical record is virtually zero.

In this interview, curator Lawrence McDonald and CIRCUIT Director Mark Williams discuss the rationale behind PALeo Neo, who it represented, and the lasting impact on institutional policies. Our thanks to the artists who supplied images and/or video.

---

Mark: PALeo Neo I remember very well because at the time I had a job at the NZFA exhibition space on the reception desk, counting visitors. So I had a three month immersion in this project and it was an education. In some ways it was a point of origin for CIRCUIT in that it gave me a complete grounding in the history of NZ video art.

Lawrence: That’s great to hear. That (influence) could be counted as one of the major outcomes of PALeo Neo.

Mark: But let’s talk about the exhibition for those who weren’t there. Its base was within the old Film Archive exhibition space on Jervois Quay?

Lawrence: It was. In the case of one work, we wanted to project to the outside world and that was the Sean Kerr Work Dot (1999), which faced traffic and pedestrians around that area. It was a big wall of monitors and it was very visible to motorists who stopped at those lights adjacent to the corner. Also people were able to walk around that area because it’s a pedestrian pathway.

Dot (1999) Sean Kerr, 12 channel video installation, New Zealand Film Archive, Wellington (1999). Image courtesy of Lawrence MacDonald

Mark: But the exhibition spread across a variety of public spaces in Central Wellington. How did you choose the spaces?

Lawrence: The site chosen was the former James Smith Building. The owner David Blackmore was sympathetic to art projects. The building wasn’t just about shops and retail it also might have (had) interesting things going on in it.

Mark: So this was kind of a mall? Which artists were installed there?

Lawrence: Phil Dadson was on Level 1. His work Physical (1976) was outside the Evolution Gym. On the ground level there was Fish Eye Discs, a record store run by Colin Morris and his associate. I chose that site to put works which had a musical dimension. They were like a kind of video music.

The opening work in this space was Noise: Theme and Variations (1998) by David Downes, who is a composer as well as a video artist, then there was a PALeo work from John Henry called Images (1976), a very abstract work which is analogous to music in its abstraction.

There was also Megazines which was a big magazine shop. That had a window which faced out to the street which they used sometimes for advertising magazine covers. I managed to get that all emptied out and put Andrew Drummond’s Walking (1979) in there. That was quite apt because pedestrians were passing it. After that we installed a short work by Greg Burke called Umbrella (1985).

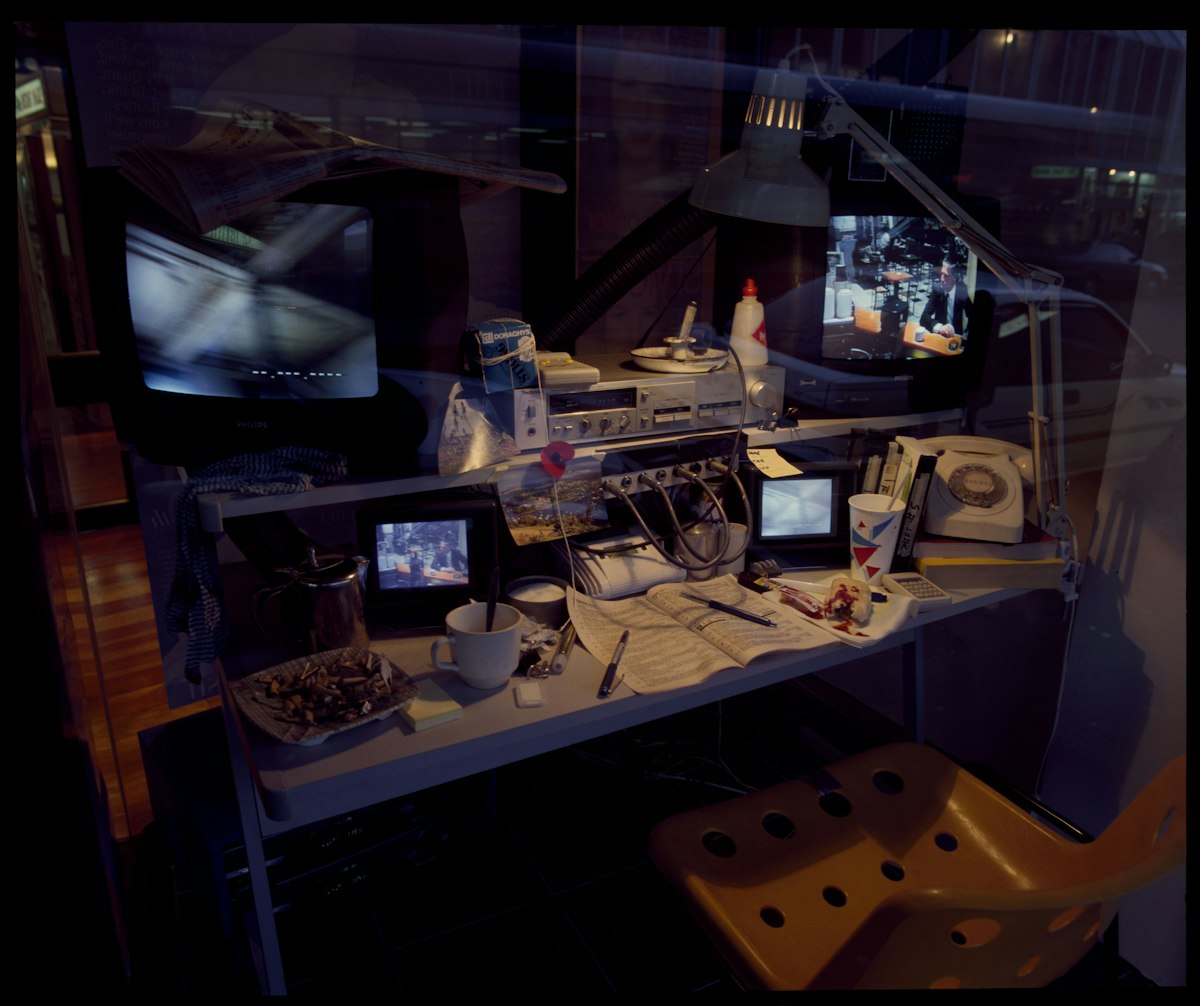

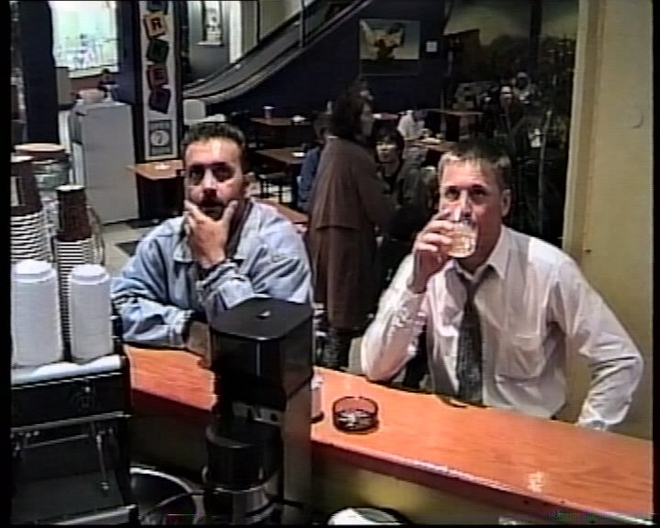

This was all as a prelude to a major new work called Columbia Saloon (1999) by Terry Urbahn. It was a security guard’s desk with monitors, and no security guard, with the signs that he’d gone off duty temporarily. It was installed in there, but it was receiving a (closed circuit) monitor feed of what was going on inside James Smith’s. At one point Urbahn went and sat at the bar and he became part of the work.

Still from saLOON (1999) Terry Urbahn, Digital Video, Sound, included as part of the installation Columbia Saloon, James Smith market, Wellington (1999). Image courtesy of the artist

Mark: Could you talk about the relationship between the video works and other artistic forms of sculpture, installation whatever?

Lawrence: Leon Narbey began as a sculptor, and Floor Quartet (197-) is essentially a light sculpture. Also in the main exhibition hall was an Andrew Drummond work Willow Dance (1980), which is very much a sculptural installation. So there’s that very strong sculptural element which reflects the history of how much video art evolved out of the sculpture department (at Elam School of Fine Arts) in Auckland, but also people working outside Auckland.

Mark: That’s interesting because people talk about Phil Dadson at Elam as being a really watershed presence in the development of intermedia. But no-one really articulates who might have brought that influence into the schools elsewhere in the country at the time.

Lawrence: I tried to reflect that by having a Christchurch presence and also a Dunedin one. In the case of somebody like Mike Sukolski, essentially all his work was initially done in Dunedin where he was working at the Teachers’ Training College. David Downes and much of Andrew Drummond’s work was done in Wellington.

Willow Dance has very much got a sculptural basis but it’s also got a very sound basis. It’s like a collaboration with composer Chris Cree-Brown whose soundtrack was remixed and re-edited to go with this show. We can talk about Phil Dadson and David Downes as composers who are also video artists, but in the case of Willow Dance it was an actual composer and an actual video artist collaborating, so that was interesting.

To put PALeo Neo in relation to VDU, it’s a very different exhibition. With VDU, it was essentially a more purist video art focused show because it had to travel. It was designed initially to go to Germany so it had to be very portable and the German galleries were offering very little in the way of resources.

Mark: So VDU was more single channel material?

Lawrence: Yes it was. It was a given that it had to be single channel material whereas I didn’t want PALeo Neo to be at all like that. There had been a moment where video got into the single channel mode in the later part of the 80s and early 90s, but I was hoping that we could get back to something of the spirit of the earlier stuff. And so that’s why the new works, whether they were Sean Kerr’s or Terry Urbahn’s or Paul Redican’s were installations.

Mark: What kind of representation was there of women in PALeo Neo?

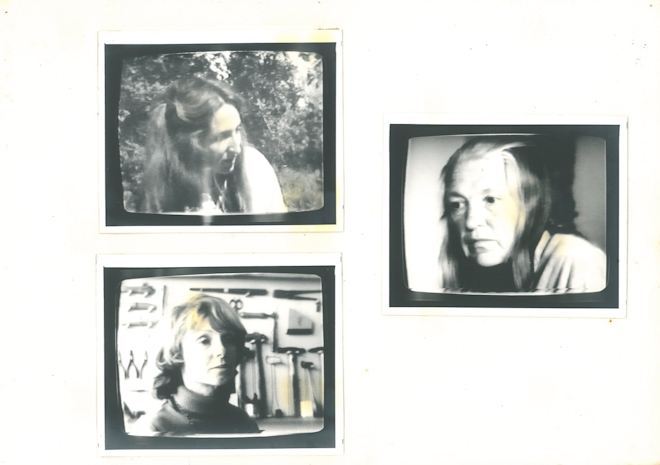

Lawrence: We had work by a group of early women practitioners, Ngaire Mules, Janelle Aston and Kate Hill. They were people working in Auckland in the Jim Allen era.

The Painter and the Emperor - A Study of the Artist as Mother (1978) Ngaire Mules, Janelle Aston, Kate Hill. Image courtesy of Ngaire Mules

Amongst the recent works we had Happiness, a new work by Julainne Sumich, an artist I’d included in VDU, whose work is quite unique and hard to classify. (In) the actual Neo compilation programme, I wanted to stress, on the one hand, work dealing with more abstract concerns, and on the other (work dealing) with media images, and recycling or playing around with those. That’s why I put Megan Dunn’s work in there.

Megan Dunn, Is America a good place for genius? (1998) Digital Video, Sound. Courtesy of the artist

Mark: What about Māori and Pasifika?

Lawrence: In VDU I had Lisa Reihana and I had Veronica Vaevae who is a Pacific Island artist. I looked at putting Lisa Reihana in PALeo Neo but as I conceptualised the show her work didn’t seem to quite fit.

Mark: One of the key works for me was Gray Nicol’s Duck Calling (1978). Was that work considered an artwork in its own right before you showed it or was it just a piece of documentation? Or did it still remain as a piece of documentation exhibited as such? How did putting it in the show affect its status?

Lawrence: I don’t think people are too hung up about asking whether this is actually an artwork or not. The context you put it in can make it comparable to the other things which were obviously conceived as stand alone artworks. I wasn’t too concerned about separating off the documentation from the non-documentation or whatever. I just thought it’s the nature of the relationship of early video art to performance.

Gray Nicol, Duck Calling (1978), Video, Sound. Courtesy of the artist

Mark: What do you think this show revealed about video practice at that time?

Lawrence: If you just take the two compilation programmes, there is only one person in both and that’s Phil Dadson. A lot of the people in the PALeo one were either no longer practising and hadn’t been for ages or had withdrawn for a period like Jim Allen.

When we look at the people that were in Neo, a lot of them also were outside of that compilation and (in) different parts of the Film Archive, James Smith’s and what have you. It’s got that same variety that the early work has.

I suppose I was trying to suggest (that) it was a good moment to look back because there were people doing things which were in that earlier spirit again.

Mark: Who would you cite as being in the earlier spirit particularly?

Lawrence: Sean Kerr and Terry Urbahn. Paul Redican’s work was like that in the same way but he also had a different kind of quality. I don’t want to call it slick, but it had a more high fidelity digital feel about it, whereas Terry resists that aesthetic. I think Sean Kerr (had an) ambivalent, almost ironic take on it. He buys into it to some degree but then I think he was poking a lot of fun at that kind of thing.

01 Products (1999) Paul Redican, Digital Video, Sound. Image courtesy of the artist.

Mark: And how did you see those works linking back to the 70s practitioners?

Lawrence: Well, I think there were no rules. It was a very free and open kind of feel that they were exploring.

In the gap between that (‘70s era) and what was emerging in the 90s, people were focusing on a kind of video making which was single channel and it was full of effects, computer generated and all that sort of stuff. I thought, let’s get back to that early spirit where video was part of a whole bigger field - sculpture, sound, conceptual art - rather than just trying to make it look like it could be on the same wavelength as music video. It was putting it in a bigger art context. I think the Film Archive, because it didn’t have any kind of particular exhibiting brief, could do that. It turned out to be a better place to exhibit it than art galleries had been for VDU.

Mark: How did you find the videos? I’ve heard the Auckland Art Gallery didn’t collect video but many of the works in the show were part of their library collection.

Lawrence: Yeah, that was where some of the works came from, and they (also) came from other institutions and individual artists’ houses. In the case of the Auckland Art Gallery library, the work was in an odd place because immediately you ask ‘what kind of preservation facilities does this library have?’ and the answer was zero. So the overture was put out that it would be good if this could be shifted to the Film Archive which can preserve it.

Mark: How did they wind up in the Auckland Art Gallery library to begin with?

Lawrence: Well that’s a good question. I’m not entirely sure. It’s very odd. It just points to a problem in the collecting of video that I identified with this project in that nobody knew where it belonged. It makes sense that it would ultimately go to a moving image archive but it would have made even more sense if it was in the main collection of the Auckland Art Gallery and not in the library.

Mark: Are there any artists from the 90s not making work now who you consider a loss?

Lawrence: It’s a shame that somebody like Paul Redican isn’t making what obviously could be classified as art. I think he now works in a more commercial corporate world. It’s hard to make a living as a video artist. Another one would be David Downes. I think composition is mostly his thing, it always was the major part of (his practice) but video was important. He’s in both VDU and PALeo Neo. As was Redican.

David Downes, Noise (Theme and Variations) (1998), Digital Video, Sound. Courtesy of the artist

Somebody who was in VDU (and) is in art histories now because she does painting is Star Gossage. She’s another Maori artist who is in VDU. Her early stuff was very much video based but then she concentrated on painting.

Mark: I lived in Dunedin in the early 90s and I remember Star and Paul and that kind of milieu that spawned them, which was a collective called Super 8. It had a couple of different venues. I remember there was quite a bit of excitement over new media in Dunedin at the time.

Lawrence: Well that’s right and those people were doing little things in obscure spaces. They weren’t really being exhibited in public art galleries as such. It came out of work being exhibited in student exhibitions and then going into smaller spaces before moving into big shows.

Mark: A lot of the artists you exhibited have ceased to make work, what do you attribute that to?

Lawrence: It’s a question you just have to keep asking. Why do people just… they do their thing and there’s nowhere to go, no career path so they bow out or do other things.

Mark: One thing you mentioned is the institutional difficulties of showing this kind of work.

Lawrence: Take your own experience for example. When you worked at The Film Archive it was still possible at that particular space to do exhibitions. Since you’ve left what has happened to the Film Archive’s exhibition policy or programme?

Mark: I think they closed the exhibition space.

Lawrence: The Film Archive made an important contribution. It was neither a government department nor an art gallery so there was that possibility to make it what you want. But I think that might have gone.

Mark: Why do you think PALeo Neo wasn’t reviewed?

Lawrence: The show was exciting while it was happening. The focus was on making sure that all the materials were there for the installations, changing works on time, and the logistics really took over. It got a lot of publicity in things like the City Voice newspaper(1) and they kept tabs on what was going on with it but it wasn’t reviewed as such.

The second problem is, there is a virtual catalogue, it does exist. It has an introductory essay by me, it has all the notes and credits for works, but they’re all loose leaf things just given out and placed in the various spaces for people to take. They were never compiled and published as a stand alone booklet or a small catalogue because the Film Archive didn’t have the resources. Probably a mainstream gallery would have ensured that happened because that’s part of their budgeting.

There’s (a) catalogue for VDU. It’s in the National Library collection, Turnbull and all that sort of stuff. In the Te Ara Encyclopaedia online there’s an entry on digital arts by Andrew Clifford and VDU is mentioned because you can access something about VDU. PALeo Neo is not mentioned in that entry because how could it be?

I suppose it points to the fact that either (someone like) yourself or somebody involved at the institution where it’s exhibited has to try and elicit these reviews. At one point there was the possibility of a review in Art New Zealand but the writer in question didn’t have the time to complete it.

Mark: Also the fact that it was in several venues and changed frequently over the duration.

Lawrence: That’s right. But I’d like to think that it won’t fade completely. There were people at the 2015 CIRCUIT symposium who were in it. Sean Kerr and Phil Dadson were probably quite happy to revisit the memory but what about people in the room who had never heard of it? I wonder what their feeling about it was when they found out about it?

Mark: I don’t know. I think if there was a bit more visual material that would have really helped to ground it. I guess it’s still kind of fuzzy this idea of a lineage in New Zealand.

Lawrence: Yeah, it’s pretty fuzzy.