Biennales the world over have always been marked by larger than life presentations and an ambitious scope. This year’s Shanghai Biennale, now in its 9th edition, was no different and with a new space to debut, there was even greater anticipation than usual. Moving out of the old, musty Shanghai Art Museum improves the show greatly and allows artists more room to play. There was a thousand-armed Guanyin steel tower from French-Chinese artist Huang Yongping, a real-life Transformer from American artist Chico MacMurtrie, and a giant motorized steel ball from Chinese sculptor Sui Jianguo. These showpieces bring in the crowds but there was plenty of opportunity to sit (or stand) quietly in the dark with a screen and your thoughts.

Still from QAQ (2012) Zhang Peili

Lu Yang maintains her reputation as a punky, proto-shock artist with another visually and aurally arresting video that employs cheap 3D imaging technology and a dissonant soundtrack aimed at unsettling the viewer. Known for her “Bio-art” installations that explored the grotesque side of modern science and technology, she once again takes a clinical approach to understanding anger within spiritual practices. The Anatomy of Rage (2011) upends the long held viewed of Buddhism as a religion of compassion; the Tibetan Buddhist god Vajrasattva is introduced with 3D modellings and medical diagrams “dissecting” the god’s physical and spiritual anatomy. The video aims to analyze the often contradictory nature of religion, but with its amped up industrial soundtrack, overly gleeful use of acid colors, and non-stop pulsating images, there is no room to think. This piece was originally shown at the UCCA in Beijing alongside traditional scroll drawings of these “Wrathful Deities”, offering a contemplative counterpart to the intensity of the videos. Without this visual respite, The Anatomy of Rage becomes no more than a glorified music video.

The curator of Lu Yang’s UCCA show was Zhang Peili, the father of Chinese video art and mentor to a generation of young artists. He makes a discreet appearance that nonetheless neatly highlights the overarching theme of his career. QAQ (2012) is a two channel installation in miniature, underscoring the forced intimacy of its subjects. On one screen is a police officer asking questions and collecting data from two thieves; facing him on another screen are said thieves, awkwardly answering. This simple but unusual set-up forces viewers to alternate perspectives, physically and mentally. It is a stark contrast to The Anatomy of Rage, which hits the viewer like a two ton anvil; QAQ leaves a profound impression simply by skewing perspective.

Still from The Movement (2007) Hemali Bhuta

There were a number of works employing documentary techniques. Bani Abidi’s Reserved, originally commissioned for the Singapore Biennale in 2006, chronicles a fictional day in an anonymous South Asian city as its residents prepare for the arrival of a high ranking official. The two channel presentation alternates between showing the effect on everyday people—traffic at a standstill, school children preparing with flags—and those involved with hosting the official: organisers preparing the theatre, local officials anxiously waiting. She shows two worlds at odds that never quite meet. Israeli artist Nira Pereg shows how simple routine can be weighted with powerful significance. It is the eve of the Sabbath in Jerusalem and the city’s ultra-Orthodox are preparing to shut their neighbourhood off from the rest of the city. Sabbath 2008 shows the determined faithful rushing about like foot soldiers, their every step like their last. And yet this is a ritual that occurs every week and for one day, they create a second city, clearly delineating the sacred from the everyday. The flimsy barriers may not look to provide much of a border but they are heavily symbolic of the conflicts of such a contested city.

On a more abstract level, Jiang Zhi, a photographer who often plays with light in striking ways, includes his first foray into video in a provocative installation that includes grand structures made of spent fireworks and a wall of shrill musical birthday cards. The Light of Transience is a dreamy meditation on light, in which the reflection on a wall of sunlight hitting a piece of cellophane is recorded without event, its gradual shifts of light so subtle as to render it nearly static. In the Mumbai Pavilion, Hemali Bhuta captures everyday objects through collage, photography, and video. In The Movement (2007), hundreds of rubber bands are strung together and shot; the result resembles an abstract painting in motion.

-1648090839.jpg)

Installation view of Mush (2012) Khaled Sabsabi

Over at the Sydney Pavilion, Lebanese-Australian artist Khaled Sabsabi married two practices and used documentary footage to create beautiful abstract images in his video installations. In Mush (2012), he projects images of different places of worship onto a suspended cubic structure, “mushing” them into a kaleidoscope affect. He uses the same kaleidoscope technique in Syria (2012), capturing every day street scenes and knitting them into beautiful mosaic patterns reminiscent of Middle Eastern architectural elements.

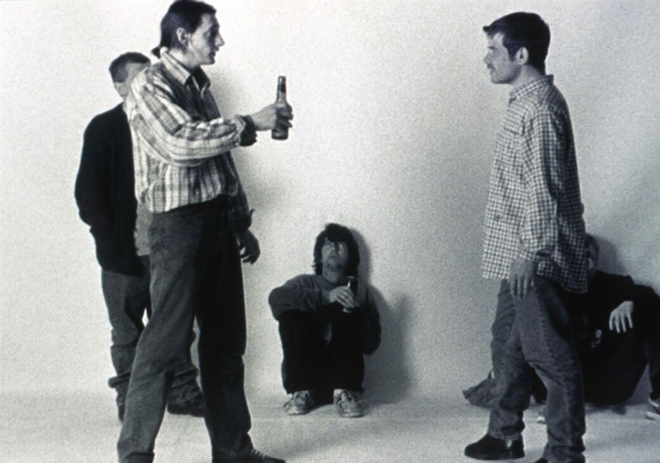

Still from Drunk (2000) Gillian Wearing

English artist Gillian Wearing’s solo presentation includes two pieces that were included in the Turner Prize exhibition in 1997, which she won that year. Her camera acts as voyeur, blurring the lines between public and private lines and exploring individual versus collective experiences. Sacha and Mum (1997) graphically delve into the intense relationship between mothers and daughters. An encounter between a mother and daughter is shown in reverse action, beginning with smiles and loving embraces and ends with what looks to be physical abuse. In between, their encounter runs the gamut from crying spells to full throttle smack down. Drunk (2000) features characters from her neighbourhood who regularly get drunk outside her studio. Bringing them into her studio, she shoots them candidly in their state of inebriation, their emotions and personal conflicts plainly on view. Though they have surrendered their private lives to public consumption, the viewer can’t help but be uncomfortable watching them lose control. (The video was taken down as of this writing, presumably for the homoerotic undertones in which the men sloppily embrace each other.)

-Wael-Shawky_CIRCUIT.jpg)

Still from Cabaret Crusades (2010) Wael Shawky

A centerpiece of the show, or at least it should be in this writer’s opinion, is Egyptian artist Wael Shawky’s Cabaret Crusades (2010), an ongoing project first shown at Documenta 13. It is a hypnotizing film, shot using 200-year-old marionettes from the Lupi collection in Turin. Shawky creates an enchanting world that belies the violence and tumult of the Crusades. Inspired largely by the book The Crusades Through Arab Eyes by Amim Malouf, it chronicles the first Crusade that devastated the Middle East and ultimately resulting in the recapture of Jerusalem in 1099. It is a dark and graphic portrayal; the puppets are expressionless and yet there is something human in their dark eyes and their mouths, painted in slight Mona Lisa-like smiles, betray a hint of emotion. It is an eerie and lyrical performance. There is no visual trickery, no special effects. Tradition is melded seamlessly with modern technology, with the puppets “acting” just as effectively as their human counterparts.