There are two versions of 19th Biennale of Sydney. There is that which is proposed in the catalogue essays and in some of the unchanged wall texts, and there is the biennale that exists within the real world.

It is impossible to separate an exhibition or an art object from its context. Our viewing modes and perceptive faculties are so influenced by socio-political contexts that to imagine that this biennale can be understood as separate from the furore its partnership with Transfield Holdings induced would be a purely fanciful.

The furore that I refer to is, of course, the boycotting of the biennale by participating artists in protest against the exhibition’s founding sponsor Transfield Holdings. Transfield Holdings has a small stake (approximately 12%) in its brother company Transfield Services who has a new billion-dollar contract with the Australian Government to run its offshore mandatory detention centres. In realising their own complicity with one of Australia’s most draconian foreign policies there was an uprising, which resulted in nine artists withdrawing from the biennale (only two remained withdrawn once ties were severed with Transfield). Amazingly, this remarkable example of political agonism led to the biennale cutting links with Transfield Holdings who had been the biennale’s key sponsor since its inception in 1973.

Whatever your perspective on these events, there is no denying that the turmoil and dynamics that sprung from the boycott thwarted any possibility of reading the biennale strictly according to Engberg’s original curatorial intentions.

In fact, it seems that despite the peak activities of the boycott and subsequent annulling of the sponsorship arrangement occurring weeks and days out from the opening of the biennale, Engberg does seem to have spun a new angle on her biennale through the canny insertion of an artwork and the rewriting of some key wall texts.

Spread across five venues the biennale for the most part responded to each site carefully, with tailored meta-themes distinguishing each grouping. The Art Gallery of NSW could be seen as the official starting point for the biennale and as such it began with an important preface. Hung in the first gallery is a neon work by "Anonymous", 2014, that reads: “MODERN WESTERN CULTURE IS IN LARGE PART THE WORK OF EXILES, ÉMIGRÉS, REFUGEES. EDWARD SAID. “ The title of this work is annotated as H.G. Wells said: A State where none go to and fro, easily and freely, loses touch with the purposes of freedom. And Edward Said… . As a curatorial framework it could not be clearer, and it is a badly kept secret that "Anonymous" is actually Juliana Engberg herself. Whilst the Curator posing as an artist is a whole other discussion, the impact of this statement upon the proceeding rooms cannot be understated. The rhetoric of these words permeated throughout the AGNSW exhibition in ways that at times seem nonsensical and at odds with an original thematic floor plan.

The placement of this work is testament to a small yet profoundly influential shift in the curatorial direction of the biennale that occurred in the weeks leading up to the opening as increasing numbers of artists boycotted the exhibition. Opposite this neon statement is a selection of works from Zhao Zhao’s Constellations (2013) series. Comprised of panes of glass that had been shot at from a distance, bearing the central gun shot hole surrounded by a network of spidery shatter marks. When viewed alongside Anonymous’ statement Zhao Zhao’s work becomes co-opted into a discussion of the recent riots on Manus Island–which resulted in the death of one detainee and the serious injury of dozens. The gunshots become symbolic of violence against exiles, émigrés and refugees. However the work that was originally intended for display opposite Zhao Zhao’s work was Ahmut Ohguts’s project Stones to Throw (2014). As one of the artists who boycotted the biennale Ogut withdrew his work that is until the sponsorship arrangement with Transfield had been annulled, whereupon he agreed to show the work. Unfortunately, as this occurred two days out from the biennale’s opening his position at the AGNSW had been filled, so his work was relegated to an ad hoc cluster on Cockatoo Island along with fellow boycotters Libia Castro and Olafur Olafsson’s work Bosbolobosboco #6 (Departure – Transit – arrival), (2014).

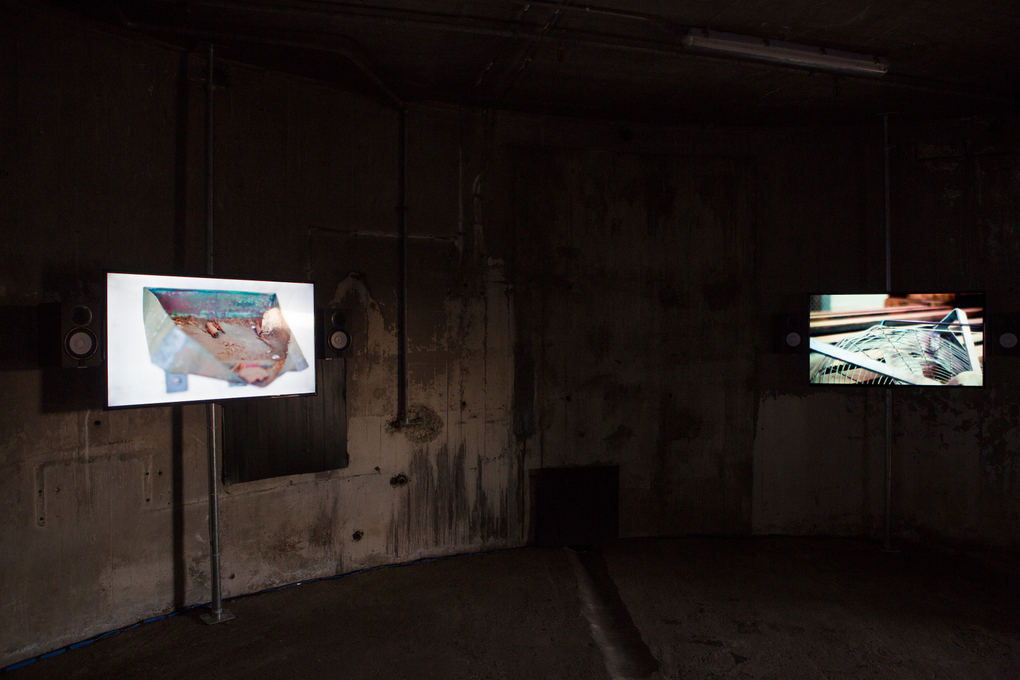

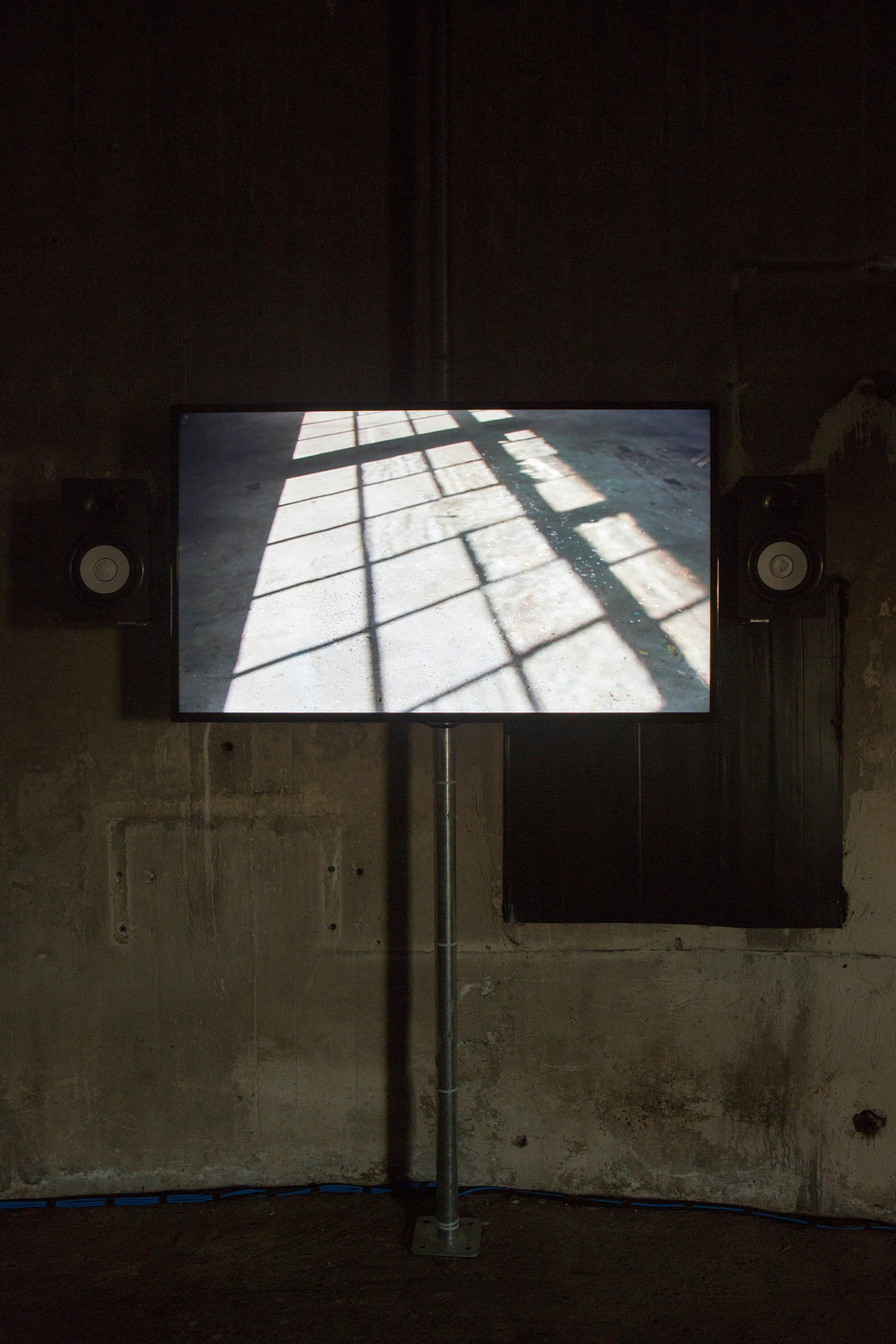

Installation view of Curtain Callers (2011) Ann-Sofi Sidén and Jonathan Bepler, single-channel HD video installation, 20 min. 19th Biennale of Sydney (2014) at Carriageworks. Courtesy the artists and Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin. Photograph: Sebastian Kriete.

This idea of absence was threaded throughout both Carriageworks and the Museum of Contemporary Art. As Engberg mentions in her catalogue essay Lacanian ideas of desire are necessarily always about lack, and the impossibility of its resolution. In the centre of Carriageworks stood an empty life-size, stage-set like house by Gabrielle Lester, Where Spirits Dwell (2014), which referenced the language of mood-setting in cinematic language. In fact at Carriageworks the setting of the stage seemed to occur over and over, with each work circling its subject without ever describing or depicting any actual content. Mathias Poledna’s A Village by the Sea (2011) seemed a self-defeating exercise in reiterating the excesses of Hollywood splendour through simply recreating its form, with little interest in its content. Likewise Hadley+Maxwell’s not unsuccessful sculptural works were comprised of the moulded wrappings from Sydney’s public art, implying a literal surface skim of ‘public art’ which is then collaged, simulacra style into new sculptural forms that referred outward beyond themselves for their meaning. Perhaps exemplifying this avoidance of a central subject, or this focusing on the language and meaning systems of art and cinema is the beautiful film work by Ann-Sofie Siden and Jonathan Bepler Curtain Callers (2011). In this work the camera pans continuously to the right revealing spliced 360-degree edits of the behind-the-scenes activities at the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm. Beautifully produced, lyrically edited and captivating to watch. Both the form and the content of this work speak of the meaning that surrounds the main event.

Likewise, at the entrance to the main galleries of the MCA are several film works that also discuss the construction of meaning, rather than bearing any meaning in and of themselves. Corin Sworns The Rag Papers (2013) uses the genre of the Detective Story providing the viewer with often-obtuse clues and hints that imply narratives, offering the viewer opportunities to formulate their own story. Likewise Ann Lislegaard’s Oracle Owls…Some Animals Never Sleep (2012-13) presents an animation of owls that speak a disjointed, often inaudible monologue, which interrogates the construction of our socio-political context. Starting any journey with ideas as open ended and untethered seems like a good idea, however the effect was disorientating, setting up a scattered and disengaged viewing stance. Engberg’s typical flair for site lines and formal connections was, however, exemplified at the MCA through her gathering together of Benjamin Armstrong’s plaster and encaustic sculptures Couple I to III, (all 2013), Gerda Steiner and Jorg Lenzlinger elegant series of collaged natural forms Souls, (2011) and Aurelien Froment’s remarkable photographic series documenting Ferdinand Cheval’s eccentrically decorated palace of personal fairy tales. Running along the corridor this grouping became a journey through the desiring and imagined worlds of personal and idiosyncratic icons and totems, ringing true to Engberg’s curatorial narrative.

Cockatoo Island was treated curatorially as exploring the trope of the ‘island’ with its associations of being “a destination, a fantasy location, a fun-park.” However also implicit within this thematic, particularly in light of the socio-political context of the biennale, is the plight of those who are held in detention on islands. Whilst some works played into the theme park idea on a more literal, family-friendly level such as Callum Morton’s ghost train The Other Side (2014); Eva Koch’s gargantuan waterfall projection I AM THE RIVER (2012) and Gerda Steiner and Jorg Lenzlinger’s vast playground of adapted gym equipment that activated absurd and entertaining interactive tableaus Meanwhile in the Bush (2010), other works referenced the island’s site and its history spatially and politically.

Installation view of I AM THE RIVER (2012) Eva Koch, video installation 12 x 6.75m. Installation view of the 19th Biennale of Sydney at Cockatoo Island. Courtesy the artist; Martin Asbæk Gallery, Copenhagen; and Galería Magda Bellotti, Madrid. This project was made possible through the generous support of the Hansen Family, and with assistance from Panasonic. Photograph: Sebastian Kriete

Remarkably Bianca Hester’s exquisite multi-platformed work fashioning discontinuities (2013-14) was the only work that referenced the original owners of the land in a statement referring to the Gadigal people of the Eora nation who referred to Cockatoo Island as Waremah. Hester’s project involved the establishments of situations and encounters that drew attention to the forces that shape space and govern our ways of life, whether they are naturally occurring or civilly imposed.

Nathan Gray’s standout video installation Species of Spaces (2013-14) portrayed a symphony of acoustic encounters from his phonic experiments with the left over industrial and building equipment on Cockatoo Island. The work becomes a testament to the potentiality of our environments and mediates the relationship between the body and our environment surrounding space. We Disappear (2014) employed the old cell block architecture of Cockatoo island organising recordings of 100 individual voices who rise and rise only to be blocked by a robotic, genderless voice that delivers instructions, admonishments and dogma. In light of their amended wall text—which includes an artists’ statement outlining their position on mandatory detention—this work becomes an eloquent articulation of the individual’s struggle in the face of oppressive or totalitarian institutions.

The poetic and political lyricism in Leber and Chesworth’s project seamlessly linked Engberg’s original strategy with that which came about through the Transfield debacle. This confluence was also evident in what was the most successful work for me Ulla Von Brandeburg’s Die Straße (The Street) (2013). In this work the viewer travels over a series of elevated undulating platforms and through corresponding curtains constructed form yacht sails. With each shift in space and visibility the viewer is moulded into a traveller, intrepid and seafaring. The work guides the viewer to a series of plywood steps upon which we sit to view a black and white film that tells the familiar story of a stranger-in-our-midst ("if you're not with us you’re against us" and so forth), combining it with the idea that the street is a kind of microcosmic family or community. The stranger is greeted by a collection of archetypal figures, who each give him fragments of their own mythologies, neither instructing nor persuading, the stranger is free to explore and experience this new world with his own curious identity intact. Epitomising Engberg’s exclamation in her catalogue essay that “here, finally, it can be said: art is desire, active desiring!”, this work is the much desired imagining of an Australia that could exist, if only our state as fellow journeyers and strangers could be collectively realized.