Comprising two films transferred to video, a floorplan for Aboriginal housing, digital prints and sound, this mixed media show offered several motifs familiar to followers of the Et Al collective.

On the wall, a series of broadsheet style posters variously combined diagrammatic motifs with text. While some brandished the weight of a masthead or historical treatise—"The Mule News", "The Colonial Empire", "The Colonial Territories"—others read as scrawled parodies of Life and Style supplements: "purified life section", "thought of life section", "composite happiness." An architectural floorplan for government-devised aboriginal house (or "moietie"), was sketched in masking tape on the gallery floor, suggesting less an ideal for living than a strategy for containment.

The dominant media of the show were two moving image works transferred from celluloid to video, labelled pragmatically as Film 1 and Film 2.

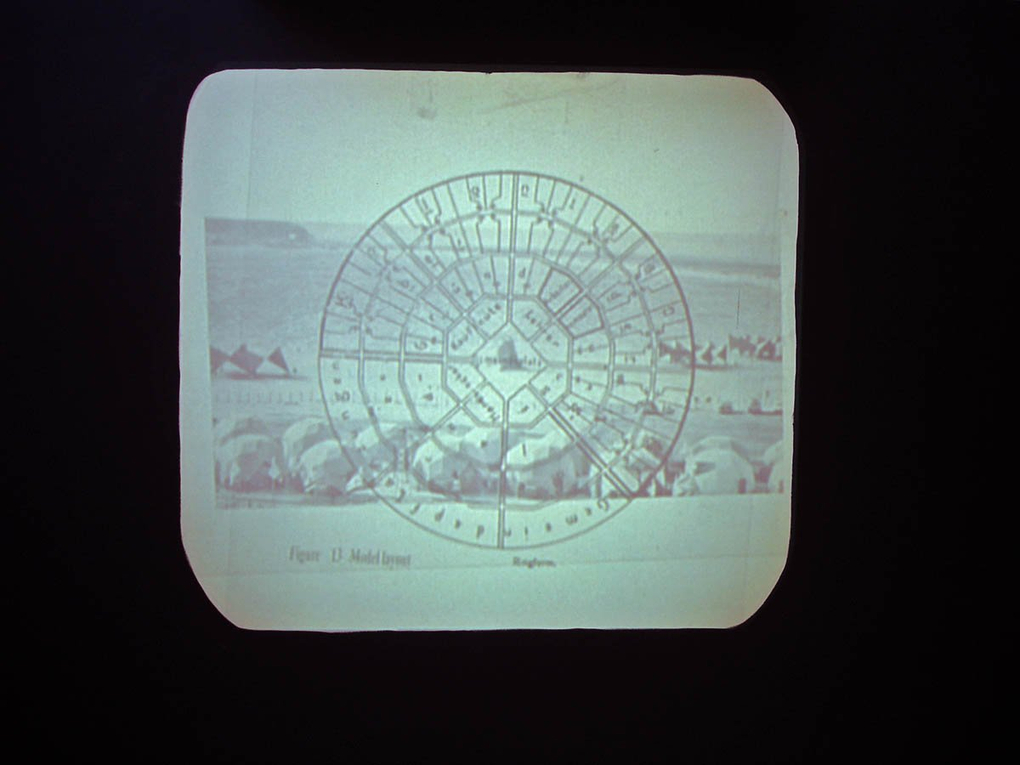

Film 1 (2012) adopts the motif of the overhead projector-assisted lecture: diagrammatic models laid over aerial views of desert settlement are complimented by a roving pencil which emerges from outside the frame to direct the viewers attention to the various details; outlining, we presume, proposed interventions in the landscape. The references are clearly to Israel and Palestine, and we see images of the 500-mile wall that separates the two countries in the West Bank.

Still from Film 2 (2012) Et al. Courtesy of the artists and Jonathan Smart Gallery

Extending from the politics of borders and territorial occupation to also encompass the personal, one diagram is accompanied by the caption “if everything in the world is not devoid of being—nothing can come to be or cease to be.” Amidst this Et Al also inserts a dash of high comedic absurdism; the caption "fig 10. nuclear induction apparatus" is followed by a felt-tip drawn tumbleweed.

Filmed in black and white, and utilising the motifs of the instructional, educational and experimental film making, Film 1 is a condensed body of stylistic modes that doesn't shrink from looking into the abyss; the introduction of fossil forms and the mapping of the brain intimate a theory of eugenics, while the layering of transparent graphics over landscape calmly asserts that the re-shaping of territory, history and people is simply a matter of human will.

Such wide-ranging stylistic references and references bring to mind the pioneering strategies of post-war cinema programmer Amos Vogel. An Austrian-Jewish exile, Vogel's family migrated to the United States in the 1938. From 1947-63 Vogel curated Cinema 16, a New York-based film society that often combined documentary, educational and experimental film in a single evening programme. The defining moment of Vogels' curatorship was his decision to screen Nazi propaganda film The Eternal Jew (1940), which in his words "outlined their case for why the Jews should be exterminated". Just as Vogel recognised the most effective indictment of evil would be to let it to speak for itself, Film 1 calmly and evenly permits power to demonstrate an image of it's own brutality.

Film 2 (2012) is an altogether more poetic piece of work whose anxieties are more personal and hard to contain. The image spills outside the edge of the painted white screen on to the surrounding black wall. While there are occasional images of muted blocks of colour, text is the prominent motif. Evoking a more anxious Lye or Kentridge, various words and phrases materialise and self-erase as vivid expressions of line. An occasional phrase catches the eye: "Impossibility of birth, permanence and destruction", "unreality of consciousness." Adding volume and mass amongst the pre-dominantly text-based work is a lump of animated clay, which rolls on screen, forms into balls, is flattened, autonomously pulled apart and re-made; an attempt at form constantly undermined by unresolved energies.

Still from Film 2 (2012) Et al. Courtesy of the artists and Jonathan Smart Gallery

Film 2 follows Film 1 with nary a pause, and indeed its opening title The Two Truths might fit either piece. Likewise, both utilise Ivan Mrsic's extraordinary soundtrack of clanging metal, reverberant tapping and unspecified workshop activity. (Amusingly, the installation was occasionally accompanied by hammering from the next door studio.)

Within both works a fundamental absurdism repeatedly surfaces to dislocate the viewer. In the case of of Film 1, these touches are often humorous, bringing into question the veracity of the voice and the film medium. In the case of Film 2, contemplation of the void is matched by a feverish making and unmaking, suggesting a drive for exploration within the self that is part survival, part creative.