"An inventory of Caravaggio’s household contents was drawn up when his tenancy ended abruptly in August 1605… Reading it is like leafing through a dossier of arbitrarily cropped and framed snapshots of the things a man once owned – the furniture he sat on, the weapons with which he fought, the books he read, the tools he used. But all the photographs are just a little out of focus. Crucial details are missing and there is no one to fill in the gaps." – Andrew Graham-Dixon(1)

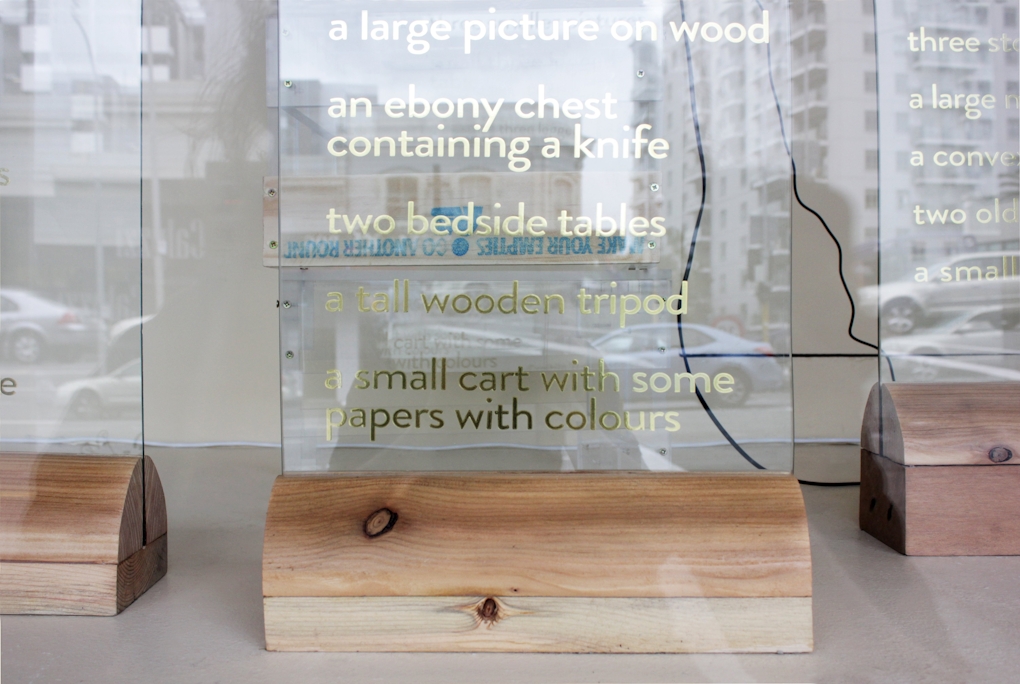

The above quotation seems a fitting place to start a discussion of Cushla Donaldson’s recent exhibition Public Dream: Liquidation. Occupying the store frontage on Karangahape Road that is the artist-run initiative Rockies, the show was dedicated to the former staff of a nearby Dick Smith store, laid off when the chain went into receivership. The inventory referred to by Graham-Dixon notes items owned by the great Italian painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610) and seized by his landlady, Prudentia Bruni, in lieu of unpaid rent. It took pride of place in Donaldson’s display, picked out in elegant gold lettering on three glass panels mounted on (equally elegant) unstained rimu bases.

Installation view of Public Dream (2016) Cushla Donaldson

The items listed are curious. While a few of them feel wholly of their time and place (e.g. ‘a majolica basin’), a remarkably large number remain plausible as the possessions of an artist living today. This is surely Donaldson’s point. Although Caravaggio died over four hundred years ago, his experiences and hardships are fundamentally similar to those of present-day artists. Artists still tend not to own their own homes (especially if they live in Auckland, as Donaldson does). Artists still need to make rent. If artists today fall on hard times, they may be subjected to repossession, or forced, like Dick Smith, to "liquidate" – to hock their belongings for whatever they can.

By referring to Caravaggio, Donaldson’s work also suggests that it can be difficult to maintain integrity when artistic production is underpinned by the need to make ends meet. Caravaggio famously battled the prevailing tastes of his time, insisting on inserting something of the grit of the world around him into his paintings. But it cost him commissions. I don’t wish to overplay the extent to which the market controls the kinds of art being made. After all, relatively few artists make their money from their art, and plenty insist on grit. But in Auckland, as elsewhere, there are patrons, dealers, and curators whose predilections artists might choose to gear their ‘personal brands’ towards.

Then, too, it might be quite a bad idea to make work that art school supervisors disapprove of. I get the strong impression that Donaldson is interested in making work that resonates with the experiences of student and emerging artists – the sorts of artists who live, work, and play in and around K’ Road. In a phone conversation, Donaldson reveals to me that the typeface used for the inventory, Brandon, is one that is currently "popular with the kids".(2) It’s a half-joking comment, from someone who is wholly at home in the company of emerging artists, and who engages with them regularly, not least because she is a host of Artbank on 95bFM, a radio station with connections to the University of Auckland.

Situated behind the inventory panels in Public Dream was Make Your Empties Go Another Round (2016), a work that strongly recalls art school life. It comprises a trio of swappa (beer) crates, remade in Perspex, but incorporating two telltale original crate panels. In principle, the work might evoke all the usual, unpleasant connotations of plastic (consumerism, environmental degradation, etc.), as well as ideas of diminution or bastardisation. In practice, it is closer to reverential. The crispness and transparency of the acrylic accentuates the formal elegance of the crates. Installed at Rockies, the light of the day would lend the objects a faint internal glow, and would throw their complex geometries against the back wall of the display.

The transubstantiation of rough wood into crystalline Perspex seems, to me, to acknowledge the importance of swappa crates in artist/student communities, not only as part of the sorts of drinking and discussion sessions that one imagines Caravaggio and his associates participating in so many centuries ago, but also as fixtures of the studio and flat: cheap, useful pieces of furniture; present-day analogues for the ‘stool’ and ‘chest containing twelve books’ of the 1605 inventory. Indeed, at Rockies, Donaldson’s crates were used as a makeshift stand for a television screen, which played a black and white video titled Heads: attempted and successful recovery of data (2016).

The video shows the artist visiting tech stores or help desks in an attempt to get the information off a computer that has given up the ghost. The issue of data loss – through planned or accidental obsolescence – is, of course, a matter of concern to many of us. In the short term, it’s bothersome. Retrieval can be time-consuming and expensive, even when it’s successful. But there are also long-term implications. In conversation, Donaldson suggests to me that we might be living in a kind of ‘future dark age’, that some of our proudest cultural achievements, those in the digital sphere, might become unknown and unknowable to people of the future.

I do not get a sense of anxiety from Heads. It is not as if Donaldson is unduly preoccupied by the possibility that her art, or anyone else’s, might be subject to loss. Instead, I get a sense of the artist’s curiosity, wondering at a distant future in which the only works that have survived in something approximating their original state are those that correspond to art forms recognised in Caravaggio’s time: drawings, paintings, sculpture. At the same time, there is often a gap between the durability of objects and the possibility of understanding them. As I write this text for dissemination online, I find myself chuckling at the vision of someone, centuries from now, trying to make sense of an orphaned Perspex swappa crate.

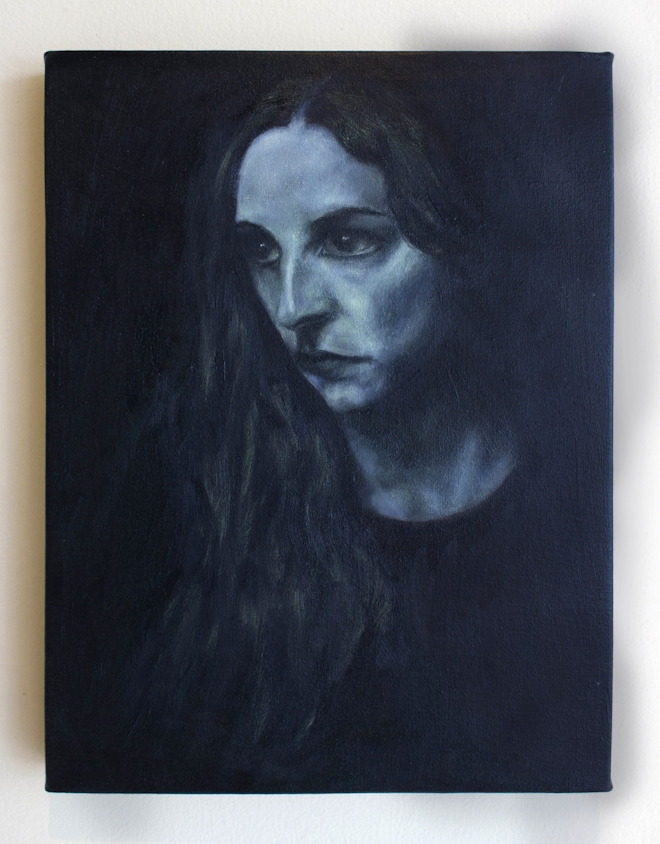

Then again, spanning as it does a diverse range of media, Donaldson’s Public Dream work is uncommonly well placed to stand the test of time. In addition to the sculptural and video elements already discussed, the show included an oil on canvas, Observer of patterns: portrait of Frances Levinston (2016). As with Heads, the painting is monochromatic. As with the work of Caravaggio, it is broadly tenebrist in style, employing strong, directional lighting, which casts portions of Levinston’s face into deep shadow, lending the piece an emotional power that is not contingent upon knowing anything about its subject, nor upon considering it in relation to the rest of the exhibition.

Observer of patterns: portrait of Frances Levinston (2016) Cushla Donaldson

This is not to suggest that the context was or is irrelevant. On the contrary, Donaldson’s decision to paint Levinston, and to include the portrait in Public Dream, was motivated by Levinston’s identity as a precociously talented and critically celebrated poet. Donaldson views Levinston as a potent, feminist role model. She explains to me that she is greatly impressed by the well-publicised success of writers like Levinston and Eleanor Catton, and that she is determined that women artists should receive similar recognition. It occurs to me that Levinston might be thought of as akin to Caravaggio – determinedly succeeding, despite working in less than ideal circumstances.

The importance of Levinston and her work for Donaldson and her show was underscored by the reproduction of one of Levinston’s poems, Scandinavia, on the glass door of the Rockies façade. The text related in interesting ways to Donaldson’s exhibition. During the day, with the autumn sun streaming in the window, the light and clarity discussed in Levinston’s poem were present in the space too. Wandering past the display at night, I thought of the interminable Scandinavian night, the inevitable seasonal answer to the "light unbroken" referred to in the poem, as well as of the darkness of Caravaggio’s paintings, which so often feel like reflections of a life that was defined as much by difficulty as by success.

It was at night that one could pick up on the finer details of Heads. For instance, footage of a family of foxes appears in the background of several scenes. By inserting this animal sequence into her digital narrative, Donaldson alludes to the posthumanist thought of theorists like Rosi Braidotti, who suggest that we are today moving beyond older notions of the human being, breaking down human/animal and human/machine divides. While Donaldson is fascinated by the idea of the "posthuman", she points out to me that the term itself is something of a misnomer, since it implies that we were all once credited with full humanity, skipping over the fact that women have long been treated more like animals than like men.

Such serious considerations have always underpinned Donaldson’s practice. But, again, it is worth noting that her Public Dream work is not angst-ridden. If it is not as immediately whimsical as some of her earlier work, it is marked by a strong vein of optimism. On the phone, the artist and I talk about the great appeal of Scandinavia, a place that often seems like an improved-upon version of Aotearoa New Zealand, in which our long love affair with neoliberalism has finally ended, and our systemic inequalities are being systematically undone. The words ‘public dream’ (which close Levinston’s poem) may be used to describe the collective folly of our status quo, but they may also be used to evoke a utopian alternative.

Installed adjacent to the poem text, and visible through it, was Ready (2016), a vinyl-cut image of a faintly androgynous, fox-headed figure in a sort of martial arts pose. Seductive, self-possessed, and totally at home in K’ Road (a red light, as well as art, district), the figure paid no attention to the most wonderful component of Donaldson’s show, Relief and Love (2016), a large soft sculpture of a bunch of grapes, hanging with Baroque sensuousness from the ceiling. Thinking of Aesop’s fable of the fox that cannot reach the grapes it desires (and so declares them sour) one might read the figure as a metaphor for the woman artist: long frustrated, but prepared now to take on anyone trying to thwart her attempts to win the fruit.

And yet I can’t help but feel as though something slightly different is going on. To me, the fox figure is Donaldson herself. She’s made those gorgeous grapes, and she is ready to make more. On the phone, the artist tells me she doesn’t like allegory. She means that she does not intend her art to be dryly illustrative or, worse, didactic. And, yet, I feel as though ‘allegory’ is a word that fits Donaldson’s Public Dream work very well, not only because the work is loaded with symbolic import, but also because it draws a compelling connection between the ideas-based art of today and that of centuries past. The constant that Donaldson makes apparent is that the true value and beauty of such art only emerges when one takes the time to fill in the gaps.