Jill Kennedy's Eyes on the Moon is a series of evocative, rich, and absurd animations that gained resonance alongside two other exhibitions recently scheduled at Auckland's Gus Fisher Gallery.

Ballast: Bringing the Stones Home presented a collection of John Edgar sculptures forged from stone collected by the artist in historic Scottish quarries. In Paper-jams: artists between the covers various artists explored the book’s identity as a sculptural object.

Programmed in tandem by curator Andrew Clifford, the three shows offered a rich survey of the similarities and differences across a range of media. In Paper-jams Patrick Pound's sensitive collages deconstructed seemingly inviolable tomes to reveal beautiful innards. Tessa Laird's cheerfully quirky ceramic books enticed but remained resolutely sealed. Elsewhere, the modernist strategies of El Lissitsky and Johanna Drucker made traditional boundaries between text and image permeable. Meanwhile in the foyer space, John Edgar’s Ballast: Bringing the Stones Home displayed the glorious physicality of worked Scottish stone, coupled with texts by Dinah Hawkins.

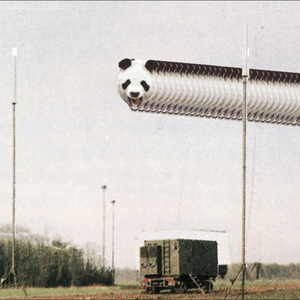

Like several of the Paper-jams artists, Kennedy combs through old books and journals for her source images. Often culled from 1960s and 70s photography and illustration, many bear the sun-bleached aura of a California snapshot. In Eyes on the Moon (2012) she endowed these images with life-like qualities, or juxtaposed them to startling and absurd effect—a macraméd plant holder slowly turns in space; panda heads propel from the earth like launched rockets; and, in time to John Payne's synthesised beats, astronauts cavort with beach balls on the surface of the moon.

Eyes on the Moon (2012) Jill Kennedy

Imagery from the 1960s and 70s has been a recurrent motif in Kennedy’s animations, dating back to her first exhibited animation Neuro-Economy (2006). In this work Kennedy used the software After Effects to animate 70s imagery, and the 3D software Maya to re-create her mother’s lounge, which Kennedy said had remained unchanged since the 70s. This era therefore possesses a variety of personal associations for Kennedy, yet while we might catch glimpses of possible autobiographical connections in Kennedy’s work, her animations do not seek to emulate the narrative trajectory of a memoir. Rather, her sequences delight in establishing a semblance of meaning and then gleefully quashing it; at times the rationale driving a particular sequence in Eyes on the Moon was based on form and shape.

Installation view of Eyes on the Moon (2012) Jill Kennedy

In the world of animation and digital filmmaking, techniques such as digital compositing maintain the seamlessness between live action and invented content. In Eyes on the Moon a deliberate imprecision in cutting out animated elements drew the viewers attention to the collaged nature of the film. The frame-by-frame nature of animation, usually hidden due to the rapidity with which images are projected, was also made physically manifest through the proliferation of duplicated elements, exposing their motion paths like an Étienne-Jules Marey photograph.

I find that experimental animation and digital media in New Zealand by and large receive less exposure within a gallery context than similar works overseas; there is a tendency to even regard such media as technological curiosities that occupy a lower rung on the artistic ladder. In contrast, Clifford’s curatorial strategy was enormously refreshing and democratic. Eyes on the Moon gained in resonance through its reverberations with the Paper-jams and John Edgar exhibitions which drew attention to the physical nature of books and text and the texture and materiality of found stone. A similarly inspired strategy was adopted by Luc Tuymans, curator of The Reality of the Lowest Rank (Bruges, 2011), which presented post-World War II artworks from Central Europe alongside paintings by Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke and animated films by Jan Svankmajer and Jerzy Kucia.

The Gus Fisher Gallery and Andrew Clifford have already initiated several exhibitions in which ephemeral media such as sound, the moving image, and digital media have played a significant part rather than be tucked away in a darkened corner as an afterthought: Roger Horrocks’ Len Lye show and the recent Sean Kerr retrospective are two examples. Perhaps the problems involved in exhibiting such media—technical breakdowns, expensive equipment, security issues—have left other curators daunted and gnashing their teeth. However, as animation and digital media continue to grow in ubiquity, and they increasingly become part of the tool-set of a collection of artists, I hope that the Gus Fisher Gallery’s example will eventually become part of the New Zealand norm.

-Jill-Kennedy_CIRCUIT_3.jpg)