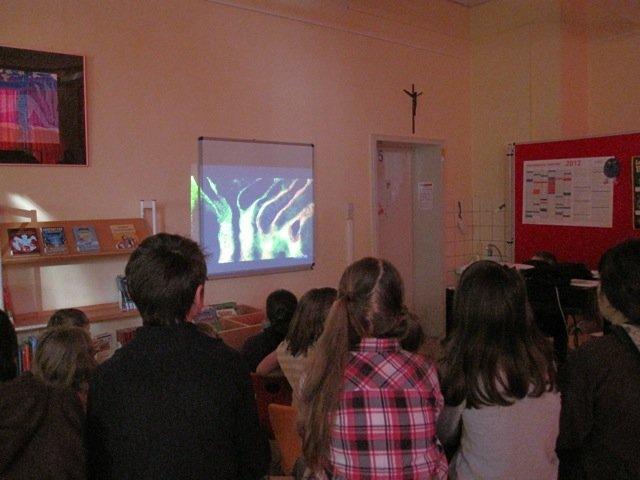

Sitting in the back row of the Star Theatre at the Oberhausen Film Festival in Germany, it's hard not to chuckle as the lights go down. Not so much at the images, but at the gleeful enthusiasm of todays programmers: a group of children aged between 6 and 10 who have selected their own public program of artist films and are pointing, laughing and yelling at the psychedelic abstractions filling the screen.

Here in Oberhausen I've watched programs by the worlds video art distributors, competition screenings of new experimental films, retrospectives of contemporary artists works and listened to several discussions on issues in contemporary moving image practice. It's been exhilarating. This afternoon, however, I'm watching a program born not of exhaustive knowledge, academic study or discursive practice, but sheer enthusiasm.

Stefanie Schlüter is a German academic/educator/programmer. Working with Oberhausen-based artist/film-maker Sara Laukner, she has led a 6-day workshop designed to introduce local children to artists films. Inspired by new films and classic works by artists such as Marie Menken and Mary Ellen Bute, the workshop is heavily based on hands-on activities. The children undertake experiments to generate visual phenomena and are encouraged to respond to what they've seen by filling workbooks with drawings and stories inspired by the films. Today's screening is the culmination of that process and presents works chosen by the children for the public.

In the foyer afterwards I caught up with Stefanie to talk about her work with the children, and why it is that young minds respond to works that their parents find difficult. I was joined in my questions by Simona Monizza, a programmer from EYE Film Institute, Netherlands who described the screening as "the most experimental abstract program in the festival I have seen so far."

We began by asking Stefanie about the workshop process.

Stefanie Schlüter (StS): The six-day workshop starts with a 16 mm projection. We don't want the children to get the impression that film is all monitors and DVDs. We invite the kids to the Oberhausen Festival villa, where we screen 16mm films from the collection of the Arsenal-Institute for Film and Videoart (Berlin).

Workshop image, Oberhausen Short Film Festival (2012)

Simona Monizza (SM): How many [films] do you have?

StS: This year it was about 18 films.

SM: So they will make a selection, the children. And do they also make the order of the [screening]?

StS: This year they made the order of the programme themselves-they just knew what to do! Last year we had to help them because there was so much sound and music in the films the children had chosen for their programme. I think it's ok if we help them here and there (but) they should be doing as much as they can on their own.

SM: And you do it for different age groups?

SS: Last we year we had 9 to 10-year-olds and this year they were 8-9. I think programming with 10-year-olds is perfect.

SM: And apart from getting into cinema and understanding films and choosing films, they also make workshops on hand painting or animating...?

StS: A couple of years ago I organised some workshops on hand-painted films in Berlin with the Arsenal cinema and film-makers like Robert Beavers and Ute Aurand. The children made experimental animations on 16mm and they directly painted and scratched on 35mm filmstrips. These films are actually in the Arsenal film archive. You can find them under the titles Kratzig 1 and Kratzig 2 (Scratch 1& 2) and rent the prints. Isn't that fantastic? The 16mm film travelled to Canada once and was shown in a festival together with artists films.

SM: We have an educational department and we do a lot of projects with schools, and we also have a big experimental collection, but the two things are not connected yet. I'm trying to collect ideas about how we can use the collection.

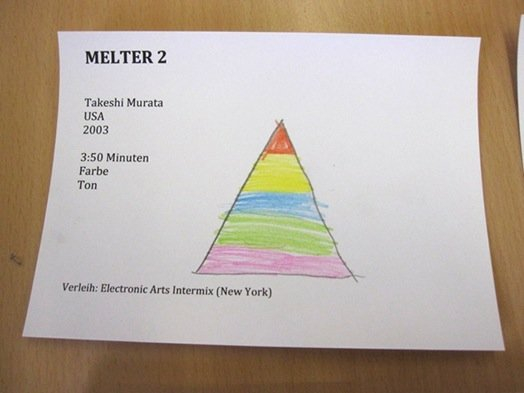

StS: Hand-painting and scratching is very time-consuming. But there are quicker ways to experiment; this year we did some colour experiments related to a a Mary-Ellen Bute film that we watched with the children. In this film you could see images of colours pouring into water. So we did an experiment with the children; we used an aquarium with cold water and we put single drops of colour in it. And the children filmed how the colours were spreading out and mixing with other colours. It's not about making a film—

SM: —it's about understanding what makes colour and light and the essence of experimentation?

StS: It's about them experiencing something and sometimes the medium helps. Last year we screened Primiti too taa, a film based on Kurt Schwitters' Ursonate. It's basically a sound poem where you see animated letters on the screen and hear somebody reciting parts of Ursonate. So [we] borrowed a couple of typewriters, these wonderful, old fashioned machines, and the kids wrote sound poems and tried to type them as images.

SM: So [the students] were using tools they were not used to.

StS: We try to take ideas from the films and use them as a basis for the children experiencing it on their own. When they first watched Primiti too taa nobody asked how it was made. But after working with the typewriters and watching this film for the second time somebody called out excitedly “I know how they made it! They made it with a typewriter!”

Mark Williams (MW): So the children were working outside of normal school time?

StS: No. We asked the schools to do it within their school time. Students tend to be more focussed in the morning and everybody tends to take the workshop more seriously in normal school hours.

MW: You've got a background in the education system. Was there any aspect of the way children are taught that you were trying to address with this project?

StS: I'm a trained teacher myself but not at primary school level. I've been a German and Philosophy teacher. I have learned about how young adults learn, how they understand, how they get engaged. The teachers training was very interesting for me and I learned a lot; but during the last couple of years I have been working on freeing myself from this experience. There was a huge emphasis on planning, and in a way there was little space for surprises in the class room.

MW: [Is] there a pressure to deliver an outcome?

StS: An outcome is compulsory in school but I believe it's more about the process and the experience. Whenever I screen films I simply ask the children, “What have you seen? What have you learnt? What have you experienced?” I see my work as a way of opening their film experience up. And school—due to the curriculum—has to be focused on results and knowledge that the students can reproduce or discuss in an exam.

Workshop image, Oberhausen Short Film Festival (2012)

MW: So how do you reconcile that desire to allow space for exploration and reflection with the education system?

StS: In Germany many teachers are limited in their abilities to approach film. They use narrative films to illustrate certain topics. Also they are very much interested in drama, a plot, a character, a development—all the topics that you would deal with in literature lessons. Teachers are not trained to think about what either a moving image or a still image is.

MW: So there's a broader manifesto in your project about encouraging questions and exploration?

StS: And connecting these questions to the medium we are working with. That's the most critical point. It's not reality, it's not a novel, it's a film and there are different kinds of film. Of course, my projects are tackling questions of film-education politics in Germany, too! One has to subvert the "official" film education policy! A good strategy with approaching some teachers was not to tell them too much about the films I am working with. There is a danger that the more abstract the films sound, the less interested teachers are. But for a lot of teachers, a whole new world opened up for them. Some of the teachers needed a hands-on experience, since the films appeared to be too difficult to "understand."

MW: So in the context of the art curriculum, is the moving image an extension of art practice as opposed to being a separate film discipline?

StS: As far as I know the art curriculum contains the word media-studies, which could really mean anything. Furthermore, I think most art teachers are trained in the classical art forms and mediums, like painting, photography, etc. From the perspective of the curriculum, film is something they could easily avoid to teach, because they can choose between different media. Maybe the younger generation of art teachers they might have some background in film and would include film into their media-lessons but not very often. For me it is most interesting to work with art teachers because they are used to abstract images. Teachers with a literary background, language teachers and also history teachers, very often have difficulties with watching abstract movies. They just don't know how to approach the abstract image in an educational context.

MW: It strikes me that kids start off working in abstraction and then they move to…

StS: …a concrete image! Afterwards it's really difficult to get them back to abstraction.

MW: Do you think that's just a part of a natural curiosity of wanting to replicate the world figuratively, or do you think it's encouraged by the teachers to move towards that?

StS: A child's life starts very abstractly, because a baby cannot see sharply. The most concrete image is probably their hands and the face of their parents, holding the baby in their arms, because they are so close. They can watch their parents' faces and their own hands for ages. But the rest of their surrounding remains abstract. After a while they have a clear vision of the objects around them. Language also helps them to signify things, but still they cannot connect their observations or thoughts in a way that makes "sense." But they love to watch and observe. They are very happy with their fragmented way of experiencing the world—and in a way this fragmented perception is abstract, too.

As soon as children go to school, language becomes a dominant tool. And with language comes the will to connect things with one other and the will to understand a deeper "sense" or "meaning." Language is something very beautiful and can be very fascinating, but in school there is no other way to communicate, teach or learn other than through language. It's just so dominant. I remember teaching a whole philosophy lesson without speaking with my students. Of course we were still using language in a way, but I was not talking, just listening. How confused they were, because they simply expect you to use your language and to talk.

Younger children are more open to abstract images because they don't have to "understand" the "sense" or search for a "meaning." The kids can just watch an abstract movie and simply enjoy it. They don't have to ask, "Why is there a yellow wave slopping over the screen? What is this film about?" They don't always complain: "I don't understand this film! Where is the story?" They simply enjoy the colours moving around and the sounds they are hearing, and it does make "sense" to them, because it's is such a joyful experience.

I think that very much of what I am currently working on has to do with questions of childhood. A child simply loves the experience of watching and listening, and this experience very often does not need words. This is what being amazed is all about, isn't it? You just sit there, like a child, with your mouth open; what you experience in that moment is leaving you "speechless"—in a very literal sense of the word. You don't have to give reasons for everything, e.g. why everything is moving on its own in an animated film. You can just simply take it as it is: as a beautiful movie, a beautiful experience to watch at and to listen to. In school you are forced to verbalise this all the time. Maybe that's the main contradiction I am struggling with in my "teaching" film. I want to get pupils back to their own perception—to where perception starts. I want them to be attentive towards their own senses—and this is a very somatic experience, too. I want to open up their perception—at least a little bit.

Imagination (1948) Mary Ellen Bute

Thanks to the Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen and the NRW KULTURsekretariat for their generous support.