Situated in the Abteilung fur alles Andere, an exhibition space located in an apartment block in Berlin Mitte, a monitor displays an image of a highly detailed mid-20th century industrial tower. Accompanied by a sonorous soundtrack the tower floats in black, digital space, as if shot from an airborne drone. Elsewhere in the room sit a series of 3D printed architectural sculptures, while in the corner, a 3D printer whirrs industriously on. One could well imagine Ghost Shelters having quite a haunting effect in a larger exhibition hall. Nonetheless the cramped surroundings give this a more provisional, experimental feel.

Ghost Shelters (2016) is an installation by New Zealand domiciled, American-born artist Brit Bunkley. Presented in the confined space of the Abteilung fur alles Andere, the installation was the conclusion of a three month residency he undertook at the Zentrale studios, part of the Institut für alles Mögliche in the Berlin district of Wedding between June to September 2016.

Ghost Shelters bears many of the material hallmarks that have signified Bunkley's practice in New Zealand; digital video, virtual environments and 3D printed sculpture. Yet Bunkley began his career as a sculptor working in traditional materials, making a number of large public art projects in the United States commemorating significant regional and historical moments.

Installation view of Gate Mask (1984) Brit Bunkley, Brick, mortar, plywood, mylar. Temporary public sculpture commissioned by the State of New York

From the beginning of Bunkley’s career he had an acute sense for the language of monuments. In his youth he was an admirer of Soviet architect Vladimir Tatlin, and a student of the Iranian artist and architect Siah Armajani. However he eventually grew sceptical of public art; the motives behind it and its capacity to convey meaning.

Siah Armajani’s effect on Bunkley is mainly evident in his approach to subject rather than any specific technique or visual style.

“Armajani’s influence was philosophical and political...made manifest by El Lissitzky’s and Tatlin’s Constructivism. Although originally one of the main proponents of public art Armajani realized the failure of public art early on.”

This disenchantment, and a desire to subvert public art’s conventions is something Bunkley has carried through to his treatment of virtual space. Many of his subsequent video works are ruminations on public spaces or public works. Others appear to subvert glossy corporate videos, or offer not-so-subtle critiques on environmental degradation and cultural colonialism. Vignettes of War and Business (2003-5) calls to mind a saccharine corporate video but is soon disrupted by the appearance of a cruise missile. The humour isn’t subtle, but it is certainly memorable. Such emblematic symbolism is the essence of public sculpture, demanding bold statements and with little space for nuance. It should therefore be no surprise that Bunkley has carried this over into other media.

Vignettes of War and Business (2005) Brit Bunkley

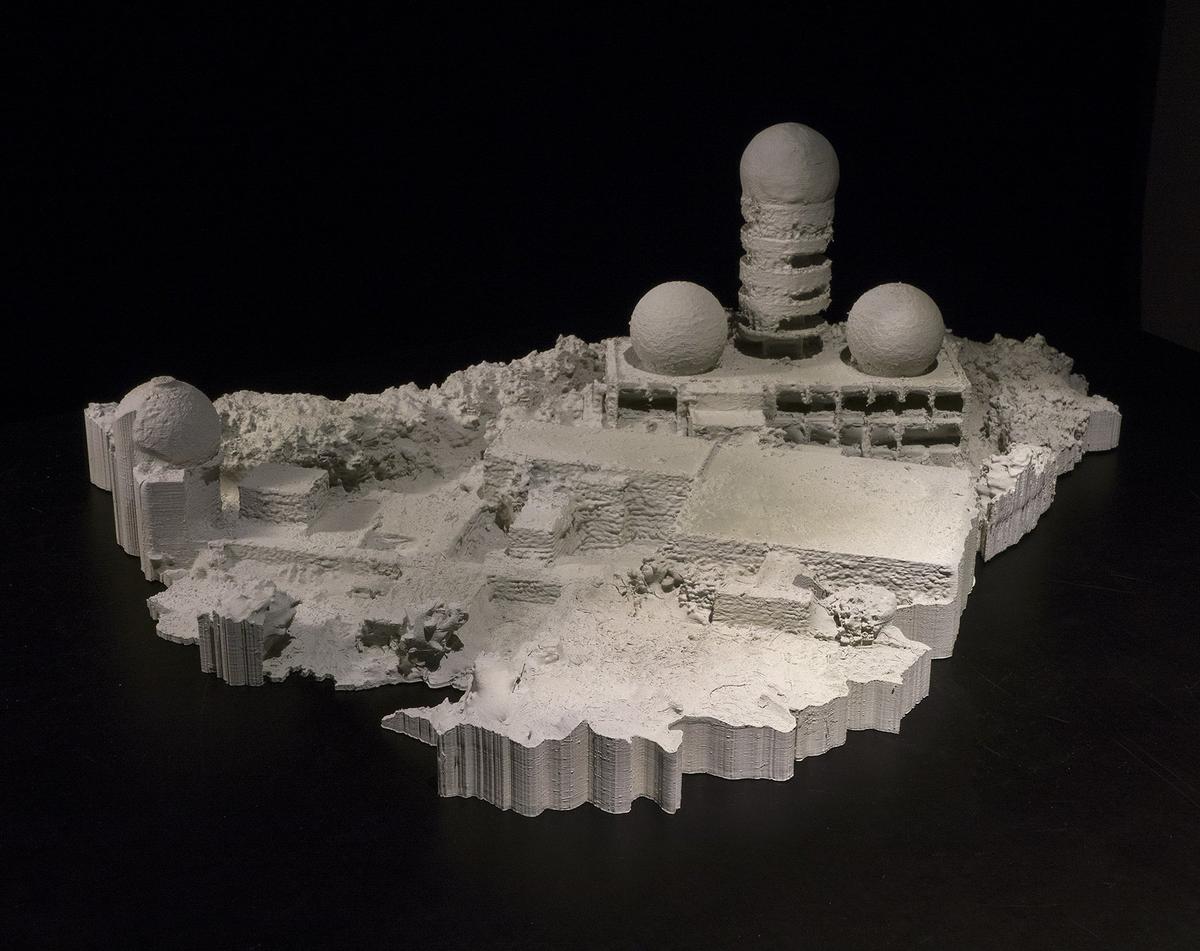

While researching Ghost Shelters, Bunkley used drone mounted cameras and 3D printing technology, reproducing various ‘abject monuments’ around Berlin, among them Teufelsberg, the defunct Allied listening post built on a hill of rubble in Grünewald, which is now a tourist attraction set amid parkland on the city’s western edge. Other architectural landmarks Bunkley modelled for Ghost Shelters included Albert Speer’s test drum (a giant concrete cylinder in the south of the city which was a prototype stanchion for a huge causeway, leading to Germania, Hitler’s reimagined Berlin), Cinderella’s Castle at Disney World (modeled on Neuschwanstein, a late nineteenth century gothic revival stately home in Southern Germany) and the entrance to Birkenau Concentration Camp.

The history of these sites themselves, although an essential part of their ‘abject-hood’ is not in fact the subject of the exercise. While the video footage has been taken in real time, and represents an object in the physical world, the overall effect is reminiscent of video games and CGI. This effect is a recurring feature of Bunkley’s practice, blurring the distinction between ‘depicted’ and ‘depiction’ and it is the materialisation of them as models which renders them tragic.

Ghost Shelters (2016) Brit Bunkley

The pieces which have emerged from the 3D printer look less like architectural or design models than something a hobbyist might have spent countless, solitary hours working over. They have been aestheticised, reduced to the realm of toys or games or the trashiest of souvenirs.

Tightly controlled and managed, Bunkley’s back catalogue of video pieces and installations can be read in a similarly prescribed way.

Though there are sometimes running jokes, like the cockroach (an oblique reference to Kafka’s Metamorphosis) which runs across the foreground in such works as Kafka’s Sisters (2014) and By Blood and Water, By Blood and Sand (2014). Both these pieces are presented in their accompanying texts as critiques. The first is based on the assertion that institutional violence gave rise both to neoclassical architecture and the works of Franz Kafka; the second addresses environmental exploitation in New Zealand and the United States. Ghost Shelters assumes an awareness on the part of the audience, not only of Kafka’s back story but also the significance of the models and what they depict - the gates to the concentration camp, the precise nature of the World War II fortifications, the ruins of the Cold War listening post in Berlin, the architectural style of the buildings. Likewise, with By Blood and Water, By Blood and Sand it is taken as given that we are familiar with the environmental debates taking place in relation to the landscape of New Zealand and of the Southwestern United States. In another video piece,The Waxing of Joy (2014) Bunkley mashes Cuban Salsa dancing with a slow cello soundtrack. Again, this work presupposes a particular knowledge from the viewers, in this case a familiarity with the mood and tempo of Pākehā society and the comic effect of splicing it with that of a section of Latin American dance.The Waxing of Joy suggests the eviscerating effect of the colonial Anglo Saxon culture; that of adopting a sensual, sexy dance and turning it into a staid and perhaps rather dull evening activity.

Still from The Waxing of Joy (2014) Brit Bunkley

We have to assume that the captions with which Bunkley accompanies these works on his website are an integral part of the works; they are explicit about what each element is supposed to represent, and how we should experience them.

Such an approach has also been part of his public monuments: Primitive Accumulation (2008) features a huge cube of tightly stacked garden gnomes. The accompanying text informs that the title derives from a passage in Karl Marx’s Das Kapital (1867), and that the significance of the gnomes was their popularity among working class Germans and their prohibition under the GDR regime. In other words, these are emblems. Of course it is possible to enjoy the work without knowing the backstory, but the connection of the work’s title and its content are quite obscure without it. In Bunkley’s CGI world, his 3D models are hollow, and the irony or the humour is played out in full sight. He works with the full awareness that a camera eye, or a drone eye, far from being a surrogate human eye, is a creature in itself. Where Harun Farocki looked at the way video games have been used in military training and resultant emotional disconnect among the troops, Bunkley focuses more on the displacement that such technology creates as a phenomenon of its own.

And the displacement generated by a facsimile - and the irony inherent in looking to that facsimile of a town or a structure in the hope of engendering the same emotions as the original - is very finely played out here. There is always a certain ambiguity whether this is an actual model or a 3D digital image. In Oil Petals (Pillar of Cloud) (2015) the movement of the dust devil looks just a little too deliberate to be naturalistic. Although we suspect that we are looking a fabrication, or an altered depiction, it is unclear to just what extent (Ironically it turns out in this instance to be unaltered). We already know that Bunkley presents fictionalized or modified versions of real things. And we are familiar with his insistence on providing a comprehensive back-story. If we take these two elements together we are being effectively instructed to read the work in a particular way. But if we treat the explanation as a part of the work, as we surely must, then that too becomes subject to the same questions and doubts as the content within the video or sculptures.

Oil Petals (Pillar of Cloud) (2015) Brit Bunkley

There is a link made throughout Bunkley’s work between ideology and environmental degradation, and in particular the structures left behind as evidence of material or social violence. The ‘abject monuments’ of Ghost Shelters and the environmental scars that mark Germany today serve as a reminder of ideologies acted out to their logical and absurd conclusion. But they are also evidence of the industrialised, technological nature of the war machine and the accelerant effect that war has both on industrial expansion and technological progress - modern jet aviation is largely a product of the second world war, for example.

Eastern Europe in general is still feeling the knock-on effects of the Cold War era’s command economy and its disproportionate reliance on heavy industry. The invitation in Bunkley’s work is for a reflection not on the particular horrors of what happened within the camp, but on the way it is rendered as a model or a toy, becoming just one more token for a fading moment in history. It raises questions too around the ways such subject matter is being presented - in formats (videos resembling games, model-making, animation) which are more commonly experienced as entertainment. As events recede into history they lose their immediate emotive impact and become tales. Pirates and buccaneers were thieves and killers in their own day, but the intervening centuries have rendered them as little more than cartoon characters.

Describing the projects development he says;

“Immerath is a town near Cologne Germany that has become a ghost town. It will be dismantled before nature has a chance to destroy it. The land it’s on will be stripped away for coal and then eventually turned into a lake...”

In Ghost Shelters, Bunkley has rendered Immerath into 3D printed models taken from the scanned drone footage - "complete with a graffitied swastika". This marks the project out from his others; while his earliest works proposed as yet unmade structures, later on he documented the surviving remnants of collective human vanity. This most recent work is distinguished since it will be a record of a place soon to disappear. And yet presented as images and models, there is a flattening effect. The shapes and forms of the town can be reproduced and printed, and videos taken in high definition and dizzying 360 degrees. The textures and colours can be faithfully replicated. But of course it is not that town, and it does not carry the soul or the memory of the place. It is an impression, it is a fossil.

Bunkley’s practice throws up many contradictions: the emphasis on the surface, yet the references are to things and ideas outside the work itself. Pessimism mixed with dry humour. The maker of monuments now deconstructing them. The insistence on spelling out the motive behind works which are supposedly symbolic, emblematic and clearly readable to those coming to them for the first time. This last appears as a further subversion of the form; another critique of the language, an act of someone whose faith in the medium has been long since lost but who also recognizes the absurdity inherent in creating such monuments and who plainly understands that their meaning will inevitably shift and change over time.

It is quite true that a ruined building is "abject", literally "cast out" from usage - but it is not the story of that casting-out which is being related here as much as the way physical decay and transformation remakes such places. Reflecting the actions of tyrants, or the ruinous impacts of corporations is not where the abject sits here. The quality of these monuments is only in part derived from their associated historical reference. They are in another sense still in currency as monuments. A ruin, in the process of its ruination, takes on a new identity. There is an oscillation between what we see, our own knowledge of what we see and what we are told that we are seeing. It suggests an almost Platonic notion is at work here; that of the Idea becoming inevitably altered through materialisation, or a thought given voice becoming something different. The processes both material and cerebral being externalised, they are transformed. Bunkley has taken the "unspoken power" of monuments and unpacked it, and laid it bare. Described in such detail, it has been neutralized.