For a spell, anyone wandering by the ST PAUL St Gallery could have seen inside its front window a steel ladder and a door ajar. There were also words in vinyl adhered to the glass and a poster suspended from the ceiling. The vinyl text spoke mainly of modalities of architectural elements and the poster pondered the way in which certain writers can have an uncanny ability to divine one’s innermost thoughts.

Alas the ladder and open door were in the window only briefly, they were not part of the installation Window/Mirror (2015) by Wellington-based independent publishing house Hue & Cry in collaboration with poet Sarah Jane Barnett and artist Ruth Buchanan. But they stay in my mind because for a moment they so perfectly enacted provisionality and openness. They created a very public and unwitting display of precariousness, preparation and working out, all concepts that seem central to curator Abby Cunnane’s exhibition The things we talked about.

Recently a friend and I have been discussing some writing by poet Stacey Teague in which she says: "a while ago i started almost exclusively reading books by women writers. i don’t think it was a conscious decision so much as i’m just more interested in female writers. it is women that i care about the most. i want to support their work, read their words, see their perspective, share in their experiences."(1) It was around the time of this discussion that we heard about this exhibition and almost simultaneously exclaimed how intriguing it looked, adding, "and it’s a show with all female artists!"

So it is from within this ambience involving the idea of publicly working through incertitude, as well as a conscious patronage of female writers and artists—that I read this exhibition. Although its title pointed to entities discussed, the works within the exhibition seemed to circulate around permutations of language, various acts of conversation and attempted verbalisation—rumination, anecdotes, dialogue, exchange, rehearsal, epistles and faxes. Cunnane writes that there is "a hierarchy of things told," and her exhibition manifests layers and levels of things told for visitors to over-hear and encounter.(2)

Telling can imply speaking and the notion of vocalisation or voice was obliquely alluded to by Alicia Frankovich’s Lover, an amorphous glowing shape suspended from a coat hanger. Neon pulsing through its thin frame evokes the circulatory system of someone who is no longer there, an absent lover perhaps. Hanger and frame stand in, making present a still stance and acting as a possible surrogate for a body, her gestures and voice.

Voice becomes the cinematic convention of voice-over in Dorine van Meel’s films which filled an adjoining darkened room with poetic polyphony and illumination. The single channel Instead to meet strangers who might change our minds (2014) is an edited film of an event that originally took place in the Swiss Church in London. At first white then eventually multicoloured lines play within a blackened space and when they fall upon neoclassical architectural features—vaulted ceilings, capitals and pilasters—it becomes evident that what has been filmed is an absence and presence of shaped and moving lights. A church organ plays highly serious, discordant music whilst an abstract play of light and shadow fade in and out with voices in counterpoint. Roomy words echo, filling space, the specific filmed architecture of the church and the physical space of the gallery, bouncing and reverberating. The words are edited, sometimes dreamy. Voices falter, then break up.

Utterly urban, Van Meel’s At Least the Oranges Come from Sicily (2015) is a film composed of gatherings of all sorts of texts and titles alluding to another cinematic convention, the inter-titles of silent film. Multiple female voices speak, quite relentless, either quickly taking turns one after the other, in unison or else over-lapping and echoing throughout the space. Words are also visualised, typed out and highlighted in varicoloured ways, sometimes appearing within a powerpoint-style slideshow, on an animated polygon and sometimes slowly revealed from black in a kind of backwards redaction and surrounded by warm colours such as pink, red and orange. Sometimes the texts are narrative, diaristic observations, others seem to be taken from advice columns, newspaper headlines, slogans or street signs seen from a passing bus. There are words that have been underlined in a book or brief descriptions of gestures such as a grandmother folding clothes or a mother warming milk in a saucepan. There is also reflection and reminiscing, many mentions of coffee, and wonderings… "what would it be like to be in a boy’s body?" Quick notes create a sense of lightness, the beginnings of an approach, the start of working through thoughts. The many voices are quick and hurried, combined with the titles they form a delicious and intense information overload.

Installation view, The things we talked about, ST PAUL St Gallery, 12 June-17 July 2015. Photo: Sam Hartnett

The way in which Van Meel conceals and reveals architecture points to three works by Ruth Buchanan included in the exhibition. An Image of a Solid (2013) and A Wavy Line (2011) exist as three different drops of fabric that divide one of the gallery spaces. The fall and fold of curtains, one hand dyed silk, one hessian and one silk crepe shape the space via diagonals and curves, creating structure or syntax. Each one screens and creates a division or caesura perhaps even a suspensive pause, like a rest in music, an exhalation… an interruption in the flow of the room. They also filter things from view, absorbing noises and slightly muffling the sounds of voices. Similar to the way in which Van Meel uses blackness to hide or mask text, Buchanan’s pieces truncate the grammar of space and bodies until one can only see outlines or silhouettes of other gallery visitors through pale silk or shoes and shins beneath a heavy hessian curtain. Such soft furnishings make the gallery seem more comfortable, less severe, belying the rigid engineering of railings and taut rope that is keeping them in place.

Buchanan’s quiet interventions are answered by Marie Shannon’s subtle, poignant and funny video The Aachen Faxes (2011). Shannon’s film recalls Van Meel’s ones with her use of titles, texts and quotations and also points to Frankovich’s absent lover with its words extracted from faxes by the artist’s deceased husband during his time abroad.(3) The Aachen Faxes consists of words in white on black over which a solo cello can be heard. Like Frankovich’s surrogate there is a play of absence and presence, an actualisation of voice in text, sent encoded via fax and replicated in video. Absent lovers return, at first from a far distance and then from beyond the grave. Shannon’s film is also similar to Van Meel’s due to its slight depersonalisation of voice, words are somewhat neutralised through the standard and simple formats they are presented in, combined with the obsolescence of faxes, screensavers and quaint powerpoint presentations.

Between Buchanan and Shannon, upon a grey plinth sits one aspect of contributions by Lightreading (Sonya Lacey and Sarah Rose). Private Hire (Sunglasses) is a pair of what appear to be silvery glasses, visor like, reflective on the outside and softly frosted on the inside. As an object they recall designer sunglasses as expensive luxury goods, purchased in transit, duty-free from airports or sported by hip-hop artists in music videos. The glasses indicate introspection, mediated viewing as well as reflection, if worn one could not really see anything whereas everyone else would be able to see themselves and their surroundings, reflected. The second element of Lightreading’s work occurred on the opening night of the exhibition in which both artists took turns reading a text aloud, one-on-one to audience members while sitting in a borrowed Maserati. The luxury automobile was parked partially inside the gallery and when sitting inside it, attentively listening, one’s view was filtered by wrapped windows which meant that the windscreen and surrounding windows were covered in multicoloured dots and splotches, more like stains then polka dots. From the front seat, through the crazed filtered windscreen, one could see Buchanan’s own curtain-filters and observe fellow gallery goers milling and mingling. One by one, listeners were invited into the car, to sit and listen to Lacey and Rose hesitantly recite a text that was being played back to them on a small listening device via headphones. Their readings were slow, slightly wooden and strange, they mentioned acts of viewing and pink frames and although refraining from naming names spoke of a legal case between celebrities over intellectual property.

Installation view, The things we talked about, ST PAUL St Gallery, 12 June-17 July 2015. Photo: Sam Hartnett

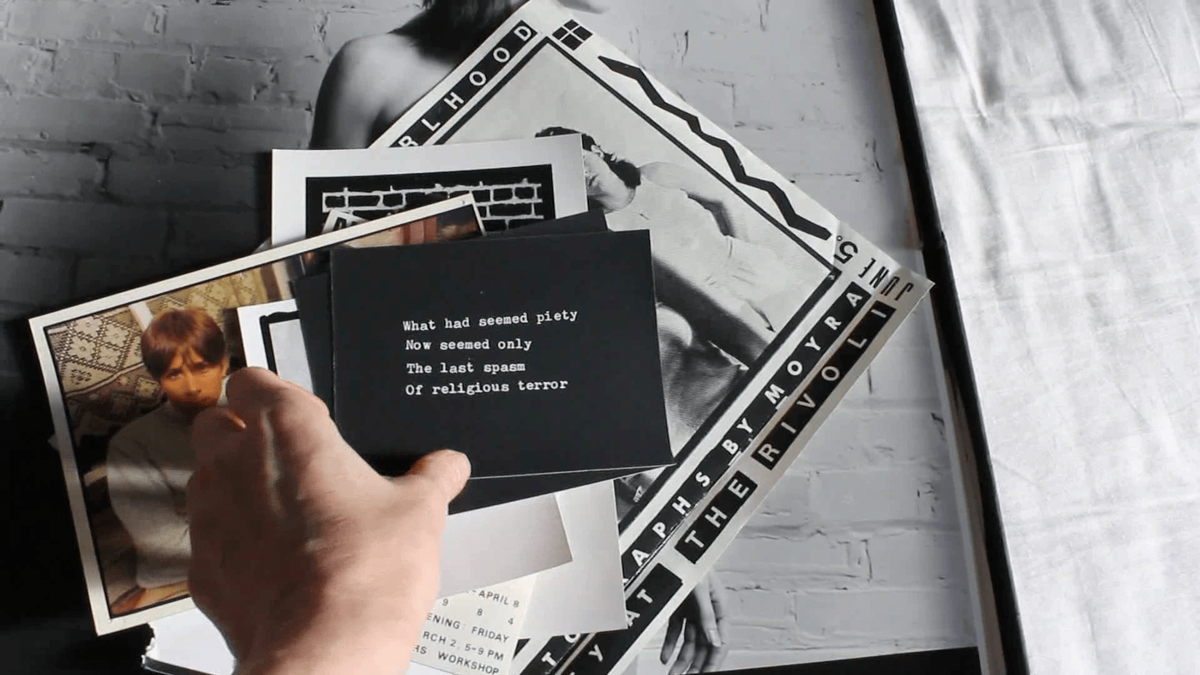

Like Lacey and Rose, Moyra Davey also reads aloud, prompted by an earlier recording of her own voice in her sixty-one minute film Les Godesses (2011). Within the exhibition, this film enjoyed its own gallery and it was very much the star attraction. It was a glory having access to the film, which was played continuously throughout the exhibition so that one could dip in and out on multiple occasions. Les Goddesses gracefully gathers together all of the themes addressed in Cunnane’s exhibition: women’s bodies, voices and stories; art-making; reading and re-reading; filming; image-making; performance; reflection; conversation; remembering; temporality; listening and writing. Davey also uses titles, a convention that in this context feels more literary, dividing her film into fragmentary chapters but also used self-consciously as errata, in order to correct herself and her facts retrospectively. There is a very public working through of ideas and thoughts in the process of being formed. Davey’s voice guides one throughout, she films herself through a mirror, from a tripod, meandering around an apartment and studio. Harking back to Van Meel is the use of notetaking and re-reading which Davey is particularly reflexive about, stating that writing from notes is ‘cannibalising myself’ and a process she refers to as pathography.

Installation view, The things we talked about, ST PAUL St Gallery, 12 June-17 July 2015. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Davey’s film also explicitly reflects upon photography and its history as a medium while simultaneously utilising digital video in a diaristic way, to create snapshots as well as pour over and sift through earlier photographic prints. Many of the images Davey re-films are self-portraits, though the most striking are intimate images taken in 1980 of the artist and her sisters, the goddesses. One in particular shows them all as forces to be reckoned with, baring plentiful bushes of pubic hair, tugging down on their underwear to reveal playful tattoos on protruding hipbones. Interwoven with personal recollection and reminiscing is Davey’s recounting of theoretical ideas and historical events. She reflects on the writings of literary figures particularly Mary Wollstonecraft and according to this aspect of the film the goddesses discussed are the infamous Fanny Imlay, Mary Shelley and Claire Clairmont. Davey reflects that an "epistolary address," one frequently utilised in nineteenth century western European literature by writers such as Wollstonecraft, is "the most useful of forms." Harking back to Shannon’s faxes, letter-writing and keeping journals are slender, provisional forms that can be highly autobiographical and it is autobiography that is at the crux of Les Goddesses and perhaps Cunnane’s exhibition too, there are many acts of recalling oneself, recounting, reciting, remembering, recording, re-reading and rehearsing. There is also research and quotation of other voices as a way in which to plumb the depths of one’s own ideas and experiences. Davey asks, "Why does everyone want to tell their story?" and why is there a "need to double one’s life in writing?"

Davey’s interrogation is extended in Cunnane’s exhibition so that it might be re-worded to ask why the need to double one’s life in art? I think this question points back to Window/Mirror, the installation in the front window of the gallery with notions of doubling and reflection. Additional posters were introduced into the window for every fortnight of the exhibition and the last one read ‘‘I want a poem to demand that both myself and a reader challenge our assumptions, for it to be both a window and a mirror." This sentence points to the way in which writing and art can be sometimes perspicacious and sometimes reflective, there is a play between what is discernable and communicable and what is not. What remains is an impetus to examine oneself, an attempt to communicate and a desire to hear from others in the hope of finding recognition or solace. Such an impetus may find its actualisation in a poem, a film, installation, an event or an exhibition.