Professor Robert (Bob) Jahnke is Ngāi Taharora, Te Whānau a Iritekura me Te Whānau a Rakairo o Ngāti Porou. In 1991 he set up the Bachelor of Māori Visual Arts Programme, Te Pūtahi-a-Toi at Massey University Palmerston North Campus where he currently supervises both MMVA and PhD candidates. Bob states he is Māori first and foremost, and sees his education as integral to his commitment towards the cultural obligations that many Māori keenly feel. Rather than citing solo exhibitions, Bob’s research highlights are the whare whakairo, Taharora and the whare kai, Hinematekaikai at his Mihikoinga marae in Waipiro Bay. In 2016 he became an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to Māori art and education.

Among his many academic qualifications (BFA, MFA from Auckland University, DipTchg from Auckland Teachers College and PhD from Massey University) Bob completed a Masters in Experimental Animation at the California Institute of the Arts in 1979. His animation Te Utu which he made while studying there is in Māori Moving Image, An Open Archive at The Dowse Art Museum 30th March to 1st July. I sat down with Bob to find out more about his time at Cal Arts in the late 70s.

Bridget Reweti (BR): Did you always want to be an artist?

Robert Jahnke (RJ): The school I went to, Hato Paora College, didn’t have an art program. So what we used to do was we’d just go along and sit the exams.

BR: Did you pass?

RJ: No I failed School C Art, twice. My brother sat it the first time I did and got something like '98 or something, it was amazing. It was huge and so I had to live up to that.

BR: And so you didn’t study art during High School, you just went to the exam?

RJ: Yeah when I went to Ardmore Teachers College in 1970 and I got my first introduction to painting, ceramics, art history and that was it. I knew what I wanted to do. So I retired from Ardmore Teachers college and then worked in a furniture factory for two years. Went to night school at the Auckland Institute of Technology to do drawing and made my wife Huia’s clothes.

BR: Oh yeah, tell me more about the clothes!

RJ: Well I designed and made her clothes. I then developed a portfolio to submit to Elam Fine Arts which included all the drawings and the clothes that I’d made. And I got into Elam. It was an interesting one, because it was a different track of getting to art school. I had no formal education in art from high school, I had to go to night school to learn to draw. I mean, I could draw, but I had to go through that system and it got me really hooked. And seeing I worked as a cutter in a furniture factory, there was a relationship to cutting patterns and dressmaking. And I would go and work there in the holidays as well, like when Elam was out and it was kind of cool. But then I went and worked in the freezing works because it was more money.

BR: How did you end up studying at Cal Arts?

RJ: Well it’s a funny story, because when I did my masters at Elam, part of it was a professional project, which became a part of the masters exhibition. So I started off with a project working at South Pacific Television, it was one of the channels then. And I worked with Peter Gossage, Star Gossage’s Dad. And of course one of the things I became aware of is that Peter had attempted to create an animated film on Māui-tikitiki-ā-Taranga. And it ran into problems because of some cultural aspects associated with it. So it was never actually realised as a form. But while I was at SPT, Peter and I worked together on developing the graphics for the channel, you know, how they used to have promos. So that kind of got me hooked and I created a relationship with these guys that had an animation studio and I worked with them on developing my own animated film. It was so basic and so bad. I hope it’s nowhere in the archives.

BR: What’s it called?

RJ: I’m not going to even name it. They helped me out, but it was so bad and I was relying on their ability and techniques but I was dissatisfied with the product. So I decided that I would find an animation school to go to and learn to do the whole film myself. So I discovered CalArts, California Institute of the Arts. It was fortuitous because I was finishing my masters at Elam, it was ‘77 I think, and I had all the stuff I did at SPT, a book that I’d illustrated and I had this moving image for the final exhibition. And I did reasonably well. Then I applied for some scholarships and got four of them.

BR: Woah!

RJ: I know. And then I had to find a place to go so I went to the American Consulate, had a look through their things and it was like going with a pin on a map, I happened to come across Cal Arts.

BR: But why the States?

RJ: It was either America or the Royal College of Art in London, and Royal College didn’t have animation. The ideal thing with the CalArts was that they had two animation tracks, one was character animation a la Walt Disney and the other was Experimental Animation. So I applied for the Experimental Animation track. And to get in I didn’t send in that film, because it was so bad, but I sent illustrations from the books.

BR: What are the books?

RJ: The House of the People, The Fish of our Fathers, The Home of the Wind. Huia just bought one recently off Trade Me. All done with Ron Bacon, an Australian children's author.

BR: And what were those books about?

RJ: The House of our People was about building a meeting house. A Tohunga went into the bush and got inspiration from the forest, the spiders, the pukeko, you know all those carving patterns, like Pākura, Pungawerewere and also the Pakake, hauling up the whale. That book got the inaugural Russell Clark Award, which was quite amazing. And then I did the Fish of Our Fathers. And that one was about building a waka, so same kind of thing you know, roaming around getting inspiration and building the waka. And that one won the Government Princes Award.

BR: And were these books coming from your time at Elam?

RJ: Well they were coming from when I did Graphic Design, I started off doing Industrial Design in undergraduate, then I did Graphic Design in the masters and it gave me the opportunity to kind of take a space which was very European. You know, the whole education system was very Western. And it gave me an avenue to research and explore Māori imagery. And the last in the series was The Home of The Winds and that didn’t win anything. So I gave up illustration after that, haha.

BR: And was Peter Gossage writing books at the same time?

RJ: Yes, yes he was. He was doing the Maui series.

BR: And was there anyone else illustrating? Creating stories from Māori narratives?

RJ: No, not really. Well, I did a book with Cliff Whiting and that one was Māori genesis mythologies. So I did one version, Cliff did another version and they combined them together for that series. But I mean, at that time there was Para Matchitt and also John Ford and Cliff, so there were those three that were illustrating. But they weren't doing it to the extent that I was in terms of tackling narrative. But they were good to see because I studied them. I researched everything they did in terms of illustration, which is you know, what you do. My portfolio to Cal Arts was exclusively illustrated books. There were two I sent over.

BR: And all Māori content?

RJ: Yeah all Māori content. And it was good because I developed a style which was different to the original books and it came out of the work with Cliff doing Māori mythology. I developed a character that became the characters I used in the film. Jules Engel, who was my mentor at CalArts, was the one that assessed the portfolio and accepted me on the basis of the drawings, my illustrations. He could see the possibility of me translating that into animation, because I sent a proposal of what I wanted to do. And so I got into Cal Arts.

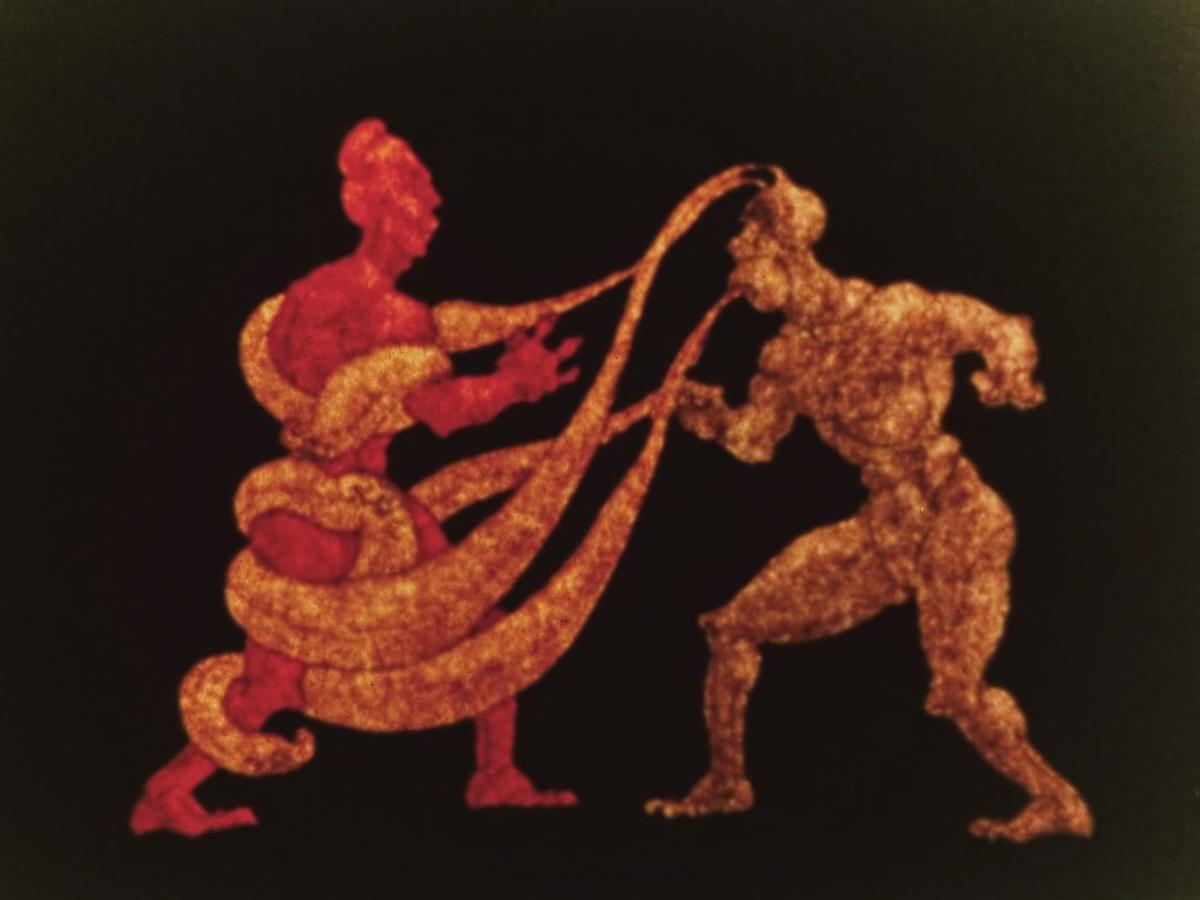

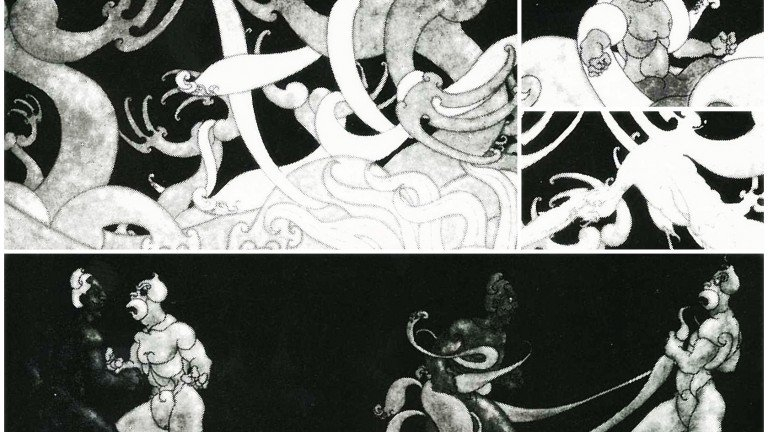

Robert Jahnke (Ngāi Taharora, Te Whānau a Iritekura, Te Whānau a Rakairo o Ngāti Porou) sketches from Te Utu (1979) 16mm animation transferred to digital video

BR: And you made Te Utu at CalArts?

RJ: Yes. Te Utu has a sequence at the beginning where it focuses on a carving, there is a cross dissolve that kind of moves in space.

BR: And did you carve that?

RJ: Yes, that was Cliff Whiting's influence on me, at that early stage. That carving is at Mangere College now.

BR: Yeah it looked like Cliff's Te Wehenga o Rangi rāua ko Papa (1969-76) that’s at the National library.

RJ: Yeah I’d seen that in ‘76, and you know he was kind of a guru then. So the carving for Te Utu was a fitting way to introduce a narrative, to reflect on the narrative that he’d done, but to use characters that I’d designed. So it was a way to commemorate the importance of Rangi and Papa and the work he’d done, Te Wehenga o Rangi rāua ko Papa. One of the things is that I had this kind of idealistic approach to animation. It was important for me that I didn’t undermine the characters. I didn’t want to turn the images into cartoons.

BR: Because of their content, who they are?

RJ: Yeah, the context of them being deity. And of course I had to work out ways of instead of Tāwhirimatea blowing, I focused on his head because of the nature of tapu. So it was using those concepts in terms of the animation. I wanted to create an animated film that considered the cultural integrity of the narrative and I didn’t want to undermine it by making a cartoon.

BR: So these were ideas you went to CalArts with, rather than them teaching you?

RJ: Yep. Well that’s why I went there. I wanted to create a film that I was happy with that realised all the things I wanted to realise. And that’s why the carving was there at the beginning. Because I wanted to ground it in a narrative that already had a history, create a relationship back to Cliff's work. So that was important. It helped translate the carved form into moving image.

Robert Jahnke (Ngāi Taharora, Te Whānau a Iritekura, Te Whānau a Rakairo o Ngāti Porou) Still from Te Utu (1979) 16mm animation transferred to digital

BR: Who did the narration?

RJ: George Henare.

BR: And the narration has a kind of Queen's English accent right?

RJ: Oh yeah, yes. He’s from that era. And he’s an actor. I mean he does Hamlet, he’s from that period. And he’s from North Auckland. And he’s famous from that period, and he was the only one I wanted. Because I’d seen him act and knew of him. The only other one I could have probably used was Selwyn Muru.

BR: And did you record him before you went over?

RJ: There were a number of people I worked with on the film in New Zealand. For example with the soundtrack, I flew back to New Zealand to do it but didn’t complete it all. So when I came back to NZ, I wanted to make sure that the narrative that I was using was okay, as well as the music which was all written by George Tait, Tūhoe. And what George did, he wrote all the narrative, the waiata, the haka. It was important to get a respected elder to do all the compositions. And at that time I had a meeting with Eruera Stirling, one of our kaumatua from the up the Coast, and Whānau-a-Āpanui. So I went along with my aunt and had a chat to him. He suggested to me that I should go and see Henare Tūwhangai who was the Queen’s spokesman, Te Ata’s spokesman. I remember going to visit him, we turned up probably about 10 o’clock in the morning, sat down, introduced ourselves and had a cup of tea. And then he talked about the Kiingitanga. I was there all day, listening to him talk about the Kiingitanga. And then at the end of the day, you know it was 4 o’clock by then, I was getting impatient, he said, ‘Oh what did you come here for?’ And I’d already sent him the transcript and he said "Oh it’s fine, I mean the guy George Tait is from Tūhoe, they know all about this." That was after sitting there all day listening to the Kiingitanga! I recorded it though and I’ve still got it on tape. It’s incredible stuff. So I also got a guy, Merv Simon, who was the head prefect when I was at Hato Paora, and he looked after getting all the music recording for me. He went to St Joseph's and recorded the waiata and the haka was done by Hato Paora.

BR: Do you know how Te Utu was received at CalArts?

RJ: It used to be on the favorite lists of CalArts. Jules Engel picked the top 20 films from the time he was at the school and that was one of them. Because it was different, and it wasn’t anything that they’d seen previously. I mean you know, weird characters running around. Because the other thing that I did too, is a kind of pixelation or atomisation through the colours. And that was created because I developed a technique using spirit based markers and I worked on bond paper and I backlit everything so the light came through the paper and the grain on paper is never consistent so it creates an atomised effect. That was just something I was interested in. When you’re working with markers it is never perfectly consistent, and I liked the fluidity of the medium and paper. As opposed to the crisp and clean nature of cell animation. And I do like animation that has the art component in it.

BR: Who did you want to be the audience, did you want it to show on television or in galleries?

RJ: It did get a showing on television at one stage when I got back into the country. And I sent it to one film festival in transit back to New Zealand. It went to the Sinking Creek Festival in the States. And it won an award there, which was pretty amazing. And when I came back to New Zealand I wanted to make another film. So I came up with a concept, made an application to the Film Commission and to Creative New Zealand, I got funding from the Film Commission but not from CNZ. And because I knew what was involved in making a film and the amount of money that was involved I just gave up and decided I’d go teaching. Because it's serious money you know, I mean it's a lot of money to make an animated film. And it's a lot of time. You can't just do drawings for a day and go out and work. You need to be constantly focussed on it. So I was totally aware of the process and hence I thought I’d change my career. That was early '80s. I finished teachers college in ‘82, taught at Mangere in the mid '80s and in the late '80s went down to Waiariki.

BR: It seems that at that time there were a lot of Māori making art, but not necessarily for galleries.

RJ: No. Not at all in fact. And even when I was in Mangere, I worked on a lot of communal projects. The focus at Mangere was kids getting an education, it wasn’t about me making art. So it was kids getting educated, working on communal projects on community halls, on the marae and even at Mangere College itself. But the galleries came much later. I didn’t have my first solo exhibition till 1990.

RJ: When was the shift into sculpture?

BR: When I taught at Waiariki Polytech, which was working with metal and timber and paint. And it’s interesting how things go, in terms of development. I enjoyed working with Erena Arapere recently making a digital sequence of images for the neon works. It almost got me wanting to go back and do animation again. But not quite! Because now that I’m working with neons, there is a potential to animate in real time, you can change them with timers. But what I tend to find is that it becomes a distraction. I like the purity of engaging with light. What it does, is what it does. And I know a couple of artists that are doing neon animation stuff and it’s kind of like going to a dance club. It’s too glitzy for me. But I’ve done a lot of sequenced work over the years. It’s sort of like an animation in a sense. It’s an animated narrative. I enjoy works that are in series. I’ve got some work coming out where the base stays exactly the same, but what changes is the poetry on the face of the work. So you engage with the narrative and there is light in the background. But it's that sequencing you know. And animation is about that. It’s about a sequence of narratives that you tie together. And I like that idea. So that’s the animation stuff, part of history!