The last iteration of Parlour’s ongoing project, Art in artist’s living spaces was presented at the home of video artists Rebecca Hobbs and Leilani Kake in Otahuhu, Auckland. Though Hobbs and Kake didn’t show their own works, various traces of the two’s practices and art collection were visible throughout the house. Inside, the eight indoor works were framed by the comfortable interior setting, while the three works outdoors became steadily more discernable as the light faded. What is so successful about the Parlour projects seems to be the whole integration of setting and scenography, artworks, visitors and hosts. In a gallery, eleven moving image works installed in such nearness to one another would perhaps be too crowded a configuration, but here, the domestic context allowed each work to stand in its own space. The suburban trappings and décor of the house acted as framing devices for each work, at once demarcating room for every piece to be viewable individually, yet connecting each to the wider composition created by the event.

Artist Joe Prisk trying his hand at walking Janet Lilo's tightrope. Image courtesy of Parlour

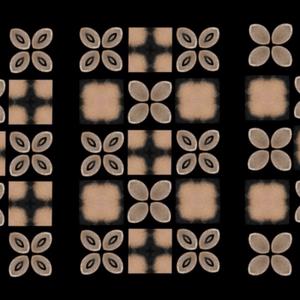

In the front garden, Janet Lilo’s slackline rope installation welcomed arrivals. The slackline was secured between two palm trees, and visitors could walk and bounce along it. With Lilo’s video projected from inside the front bedroom, the scene outdoors reprised the video and rope component from the greater body of work, Hit me with your best shot. Slacklining is relatively new sport that while similar to tightrope walking, is perhaps more user-friendly, allowing for more playful gymnastic feats than its high-tension counterpart. Lilo’s installation offered an immediacy to the work, and an entry point into the exhibition, and younger guests in particular took enthusiastically to the slackline. The set up of video and its object, their insertion into the home setting and the participation of spectators were demonstrative of the way the components of audience, exhibition, home and artwork engaged with one another throughout this event.

Walking down the driveway, people were gathered on the grass near the garage, drinking beers, snacking and chatting. The gathering was strikingly dissimilar from conventional exhibition settings, and in many ways was more similar to an early summer barbeque in its relaxed conviviality. It was still too light for the outdoors projections, and a guest wearing a black t-shirt stood opposite the projector beam in order to test the aspect ratio. There was a sense of something quietly coming to life as the sun set and the projections become more vivid and defined.

When I moved indoors from the back entrance, Ahilapalapa Rands’s RED was installed against a divan swathed in a red striped cover. The video – a luxuriant red curtain being pulled and rustled by a cream and white cat – balances a kind of Lynchian unease with wry humour. Lush and appealing in its content, my initial impression was also of a subtle sense of displaced anxiety. The empty divan added its own particular drama to the install; in a previous incarnation of the piece at Ferari Gallery, a long red curtain draped over the monitor. In both cases, these material elements keyed up the video work to create a vaguely troubling sense of campy scene design. There’s a canny sleight of hand at work here, I’m unsure whether to laugh or be worried, and neither reaction feels quite right. In this manner, RED set the scene for the entrance to a house that functioned here as both home and staged setting. Rands uses elements that are simultaneously familiar and unsettling; the deliberately composed installation destabilizes the known territory of the home environment, while at the same time, the work humorously elides overly dramatic narratives and exposition.

Installed by the bathroom, Kah Bee Chow’s Flightless, is a slowly transitioning piece that shifts between views of the snow falling softly outside a modernist building in Berlin, to a slow pan around a group of ice sculpted penguins that were filmed in a touristic amusement park in the Swiss Alps. Penguins are an ongoing concern in Chow’s recent works, so their presence here gestures to an enduring plane of inquiry, while Flightless as a standalone work is a coolly detached document of place, culture and environment, of strangeness and familiarity. By contrasting the evidence of the very human project of habitation against the wintry landscape, and against the strangeness of the scripted scenography of the tourist park, Chow records our ambiguous relationship to our environment, the funny ways we make it both habitable, and legible to ourselves.

Installation view of Flightless (Parlour edit) (2013) Kah Bee Chow

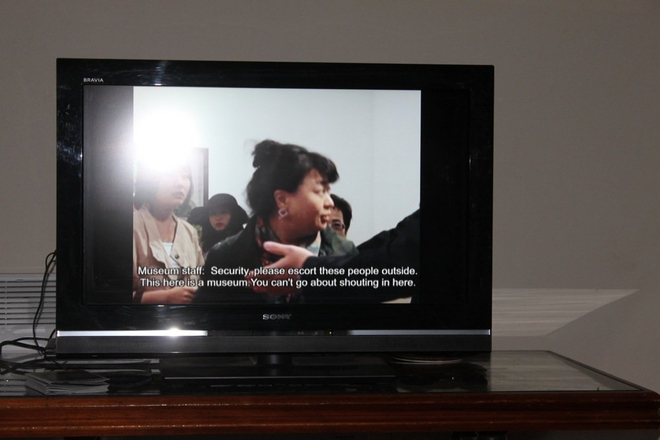

The interior environment of No. 6 Papaku Rd was activated to engage the video works with the regular features of a house: the dining area was generously laid out with food and drinks, and Naoto Kobayashi and Mai Yamashima’s Candy was also displayed here. Filmed over six months, the work documents the duo’s progress in licking down an enormous ball of candy into a bite size piece. Sometimes attacking the ball together, and sometimes alone – the travail is comic, sickly, lonely, intimate, and exaggerated in its absurdity, but condenses a simple humanity into the gesture. Meanwhile, to more theatrical effect, the family drama that plays out in the work from Enterprise of Temporary Consensus was shown on the television monitor in the living room. The tensions, old rifts and ongoing slow burning resentments of family relationships are scripted and acted out in this short narrative piece of a family’s internal politics. The rancor rises throughout the piece, each character holding on to what seems to be years of bitterness and dissatisfaction, while trying to keep it together in public. The work comes from the Nakwon Family Series project, an ongoing set of collaborative projects that instigate responses to the dramas of family politics. Here, the story that played out on the TV set in a suburban living room was a neat fit, incorporating and referring to the physical and emotional spaces of family and domestic life.

Nakwon Family Service Performance (date unknown) by Enterprise of Temporary Consensus

Providing a gentle respite from the heightened emotions emanating from the television, Deborah Rundle’s Fact, Fiction, Forecast looped a 2:26 minute video of the view from what seems like a boat cabin. Framed by shadow, only a small oval of the curtained window and its view of sea, sky and land is visible, and the video’s motion gently rocks the perspective. Rundle’s artist statement maps out a preoccupation with spatial language and the formation and stability of the subject, this piece, which emphasizes the position of an imaginary occupant, delays any arrival at a destination (whether emotional, mental or physical – as the boat never arrives anywhere), in favour of a extended meditation on position, view, subjecthood and interior space. The interior here is positioned in relation to an outside, (yet is sealed off from it) but also gestures to the inner space of the mind, the body that sits looking.

Through the hallway, Sophie McMillan’s One Two Three, was rear projected from a bedroom, with the screen suspended in the hallway near the front door, mimicking the setting of the video. This work forms part of a series that stars free-floating geometric shapes, hovering and dancing of their own accord in various environments. The work itself, and the series of videos that surround it in McMillan’s practice, are kind of comically weird interpolations into otherwise ordinary or familiar spaces. In this work, the plays of light and darkness flicker with the wavering, twitching shapes, which take on a kind of daft personality of their own. The recursive, mise-en-abyme style of installation (a hallway framed within a hallway) is faintly suggestive of the uncanny, though if ghosts are being summoned here, perhaps they are of the friendly variety.

One Two Three (date unknown) by Sophie McMillan (in doorway) and Untitled (date unknown) by Ziggy Lever

Ziggy Lever presented a piece that in its silence and stillness was perhaps the most reserved of the work on view. In Untited, 2013, a close shot sits evenly on a piece of china; the willow pattern that decorates it is visible but not totally revealed, and the extended, motionless focus on the cup forces an encounter with an object that is not quite declaring itself. But delving deeper into Lever’s work, his interest in the china extends into the histories of the Chinese willow pattern. Appropriated in the 18th Century from the decorative patterns on Chinese ceramics, the design has been in use ever since, and has become ubiquitous in china collections in homes in New Zealand and beyond. The protracted gaze on the teacup suggests a different kind of ghosting, a historical palimpsest of references, language and activity in the domestic setting that Lever reconsiders in this work.

The relative quietude of these two hallway works elevated the action that played out in Darcell Apelu’s piece, where a woman sits with her back to the camera, a lava-lava around her waist, and her top half bare. The figure sits in absolute stillness against a black background, just long enough for viewers to become quite conscious of waiting, and watching. Suddenly, a hand comes out of nowhere, and slaps against the woman’s back; the skin slowly turns red, and a welt raises. The spot lit figure that sits quietly in the dark and the quick, sharp direct action are both confronting: the deliberate yet open way Apelu engages the viewer is compelling, and she both sets up and then undermines the power relationships between viewer and viewed. With such a work, the audience’s own loaded expectations about power, violence, subjectivity, the body, gender and race are tested. The piece tests for reaction, heightening awareness of the ambivalences attached to identity and of our own position as viewers. I was interested to consider this work in the domestic context of this event—how the idea of the “home” space might impact upon our reactions to the questions Apelu prompts, how a sense of being in private space, as opposed to a gallery setting, might raise different, more personally subjective issues for viewers.

Outside, John Vea’s 29.09.09 Tribute to Samoa, American Samoa and Tonga played against the garage entrance. In the rolling surf, the artist stacks cinderblocks into pyramid formation; his attempts are often vanquished by the waves, but he labours on, achieving moments of near success before another tide of water knocks the blocks down again. There are comic moments where a particularly promising stack tumbles back into the surf, and the endeavour seems quite endless until a moment, which seems to happen seamlessly, where the formation is complete, and the sea washes and tumbles around and through the cinderblocks. The seemingly arbitrary activity and the sense of duration, effort and sustained focus on such a task is reminiscent of the allegorical travails Francis Alys scripts against various landscapes, and there is a sense in Vea’s work of a narrative lying beneath the surface. Like the wash of the waves through the concrete blocks, this thread surrounds and filters the work, moving around and through the piece.

29.09.09 Tribute to Samoa, American Samoa and Tonga by John Vea

Finally, Sriwhana Spong’s Beach Study on the adjacent wall of the garage was a sympathetic accompaniment to Vea’s documentative and poetic form of storytelling. Using 16mm film, Spong makes use of coloured filters to wash over the images, flooding the film with hot pink, tawny yellow, crimson and violet flashes while a female figure practices dancelike movements amidst the sand and tussock. Beach Study is a dream like portrait of both figure and landscape, the nostalgic qualities of the film and the wash of the coloured overlays impart a flickering candescence to imagery that seems drawn from the uncertain territory of memory and imagination.

By mapping the spatial and psychic geographies of place, memory, culture and the daily life of the home, Parlour created a composition of moving image works that spoke in dialogue with the issues we attach to place, and our own conceptions and relationships to our environments. The setting and atmosphere of the event was distinct from a conventional exhibition, but yet was still more than just a friendly gathering. In its sociality and generosity it made visitors feel comfortable enough to stay well into the night, talking freely and circulating through house and garden as familiar, comfortable spaces. But the work did more than provide an interesting backdrop for a party. Instead, it emphasized that environment, and our expectations of what different spaces might do or be, are perhaps melded to the ways we socialize and interact. Calling attention to how we cast our relationships to art and its display, the Parlour project created a zone where the work could fit seamlessly into its surrounds, sharing space with people, home and social activity, yet also inhabit a space of its own. It housed a family of works and cast them in dialogue with each other, creating links and relationships between them, which have lingered past the close of the night.

The Parlour crew L-R Vera Mey, Lydia Chai, Kirsten Dryburgh, Harriet Stockman