In this interview with James Hope, Brit Bunkley discusses three 2022 videos which use consumer software to create something approaching the ‘deep fake’.

Conceptually, these works find him revisiting long—held themes; Anarchy as a political movement, and the accelerating pace of climate breakdown.

The result is a series of video tableaux which combine 3D renderings with actual footage, creating an uncanny merger of the natural and constructed world.

James Hope: How did you first encounter deep fakes and begin creating artwork with them?

Brit Bunkley: I saw an advertisement for MyHeritage, which is a genealogy website. They developed a new gimmick called Deep Nostalgia. Have you seen that?

James Hope: Yes.

Brit Bunkley: It’s all over the internet. You can have five free animations, so everyone does it. One uploads a photograph online. The software can identify an eye and a mouth and animate them in 3D. MyHeritage used some of their employees to create set animations that include dancing, blowing kisses, a compassionate look and so on. I felt like I could do something creative with it.

James Hope: The 2018 MyHeritage application came not long after a Reddit user put an actress' face on a porn stars body. So I guess the first application of deep fakes in the public realm was a nefarious one.

Brit Bunkley: Yes. And these Deep Nostalgia animations spook a lot of people too. It's like they have just woken up from the dead.

James Hope: There's a range of quality.

Brit Bunkley: They were supposed to have achieved the ability to move other parts of the body in addition to the face, but they haven't yet. But a number of software applications and plugins exist on the market that will allow one to put faces onto 3D meshes. Something that interests me is the photorealism of new rendering tools such as Corona Renderer. It’s able to achieve near-photographic outputs within an hour for a single frame.

You saw the video I made about the deer walking through places, right?

James Hope: Yes, Dear heart, how they dream, how we dream (2022). The video juxtaposes 3D renderings of a Père David's deer with architectural interiors. Could you talk about the ideas behind that work?

Brit Bunkley: Having grown up on the East Coast of the US during the Cold War, I have always been engaged with the spectre of an apocalypse. That anxiety has accelerated recently with the ongoing reality of global warming. So there's always been the idea that human life could end.

Additionally, I've come to appreciate the idea of animals possessing a very soulful intelligence. Most people haven't begun to appreciate that until recently. I like the idea of animals inhabiting human space, not only physically, not only metaphorically, socially or politically but also psychologically.

Brit Bunkley, Dear heart, how they dream, how we dream (2022) (excerpt)

James Hope: What is the significance of the Père David deer itself?

Brit Bunkley: They are, in a way, a sort of a “deep fake” deer. Although reintroduced to China, they are still officially extinct in the wild. They are being bred here in NZ and in the USA for hunting trophies.

They look like mythical animals. Their antlers grow all in all directions like tree branches instead of growing forward like most deer. Additionally, they have these unusual noses and long donkey-like tails. They are the duck-billed platypus of the deer world.

James Hope: I was looking them up on Wikipedia and the way the Chinese describe them is really interesting;

“The species is sometimes known by its informal name, sì bú xiàng… literally meaning four not alike… or like none of the four...The hooves of a cow but not a cow. The neck of a camel but not a camel. Antlers of a deer but not a deer. The tail of a donkey, but not a donkey.”

Some sort of chimerical animal.

Brit Bunkley: Where I grew up in New England there were deer, but not on the Island where I lived. Now it’s filled with them. People like them as a reminder of the wilderness.

Now in New Zealand, where deer are considered pests, our region has been inundated with deer who escaped from deer farms. Sometimes the paddock outside my studio in Whanganui has four or five. It’s surreal.

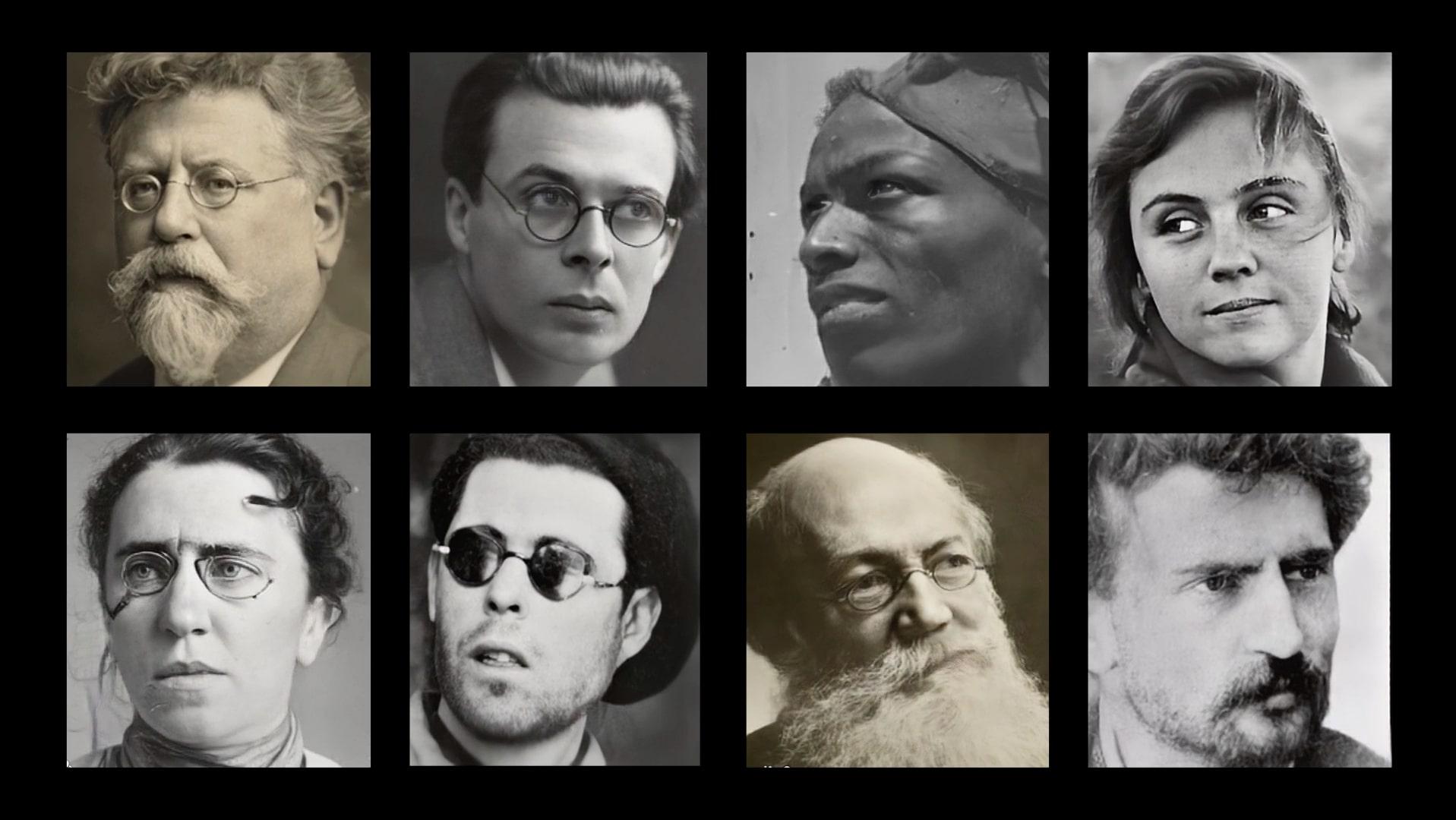

Brit Bunkley, Deep Nostalgia—The Anarchists (2022) (excerpt)

James: What about your work Deep Nostalgia — The Anarchists (2022)? You’ve been interested in the history of anarchy for quite a while?

Brit: I’ve been working with the idea of anarchy in videos for 20 years. I’m fascinated by the philosophy of anarchism as a stateless, classless society where people of all stripes cooperate, especially Green Anarchism as professed by the late Murray Bookchin. Anarchy was taken seriously in the early part of the last century. People like Bertrand Russell, Mahatma Gandhi and Franz Kafka were followers. Personally, I’m agnostic on how a permanent anarchist system would function, but my use of the Deep Nostalgia software is an attempt to humanise a concept based on intellectual conviviality and mutual aid.

The anarchist history in Spain was long and rich. The Spanish spent 50 years preparing for their new society, realized briefly during the 1936 Spanish civil war. They developed anarchist schools where science and literature were held in high regard. The first country to enact into law an eight-hour work week was Spain through the powerful anarchist CNT union.

And, of course, some anarchists were indeed quite violent. The history is quite complex. But for the most part, it has been ignored or distorted by modern historians.

James Hope: The use of smoke in Dear Heart and another work, Pillar of Fire (2022) adds a mystical or magical element to those videos.

Brit Bunkley: I first saw Dust Devils about five years ago. I drove over a hill in the California desert, at first it looked like columns of smoke in this valley but in fact it was 12 or so dust devils. Some of them grew up to hundreds of metres tall, like cloudless tornadoes.

Navajo consider this phenomenon the ghosts of the dead. If they spin one way, they're evil. If they spin the other way, they're benevolent ghosts. When I was in Arizona 3 years ago, surrounded by wildfires, I turned my attention to the fire version of dust devils, the 'fire tornado'. Both are caused by rapidly spinning heat updrafts.

Brit Bunkley, Pillar of Fire (2022)

James Hope: The notion of conjuring up ghosts of the dead plays into the Deep Nostalgia phenomenon as well.

Brit Bunkley: Oh yes.

James Hope: I guess there's a lot of folkloric tales of inanimate things that come alive. Pinocchio, the gingerbread man. And the Jewish Gollum, an animation of an inanimate thing, in this case an image. But in the original Gollum mythos it’s animating an entity from clay which can be used for altruistic or nefarious purposes, which is the same as deepfakes.

Brit Bunkley: Yeah.

James Hope: It’s interesting to think that deep fakes could become so realistic that someone could potentially fall in love with one.

Brit Bunkley: As in the Pygmalion myth.

James Hope: How do you think these artworks will hold up as an artistic works, say 2,3,4,5 years from now when the technology has become so seamless?

Brit Bunkley: Who knows. I can't predict the future. There is something a little bit odd about superimposing the head on the still body. That will probably look a little dated when the software advances and where the whole scene is animated.

James Hope: In Deep Nostalgia—The Anarchists you say you are humanizing the anarchists. But as technology evolves and deep fakes become indistinguishable from reality, people fear they will no longer be able to tell what is real and what is not. Do you have the same pessimistic outlook?

Brit Bunkley: Well, the whole AI revolution is pretty scary. What is real, what isn't real? Is AI going to make deep fakes themselves? Meaning that AI achieves some sort of consciousness.

James Hope: There is a term ‘reality apathy’ where people get exhausted trying to figure out what is real and what is fake, and they just give up.

Brit Bunkley: Yes, I mean it's hard enough with the Trump phenomenon. You just say something totally bonkers enough times and people will believe you. However, 3D computer rendering is a highly resource-hungry medium. I've been doing it for 30 years. I thought by this time it would be much further than it is. It still takes up to one hour to render a single photorealistic video frame. With 25 frames per second, we are nowhere close to creating convincing moving images in real-time. Computers will need to get many times faster before we really have to worry about total deep fake.

James Hope is Curator—Art at Ashburton Art Gallery.