What role does art play in social practice? When is it necessary to make an artwork and when to take direct action?

In this conversation, artists Dieneke Jansen and Heleyni Pratley discuss using art as a tool for social justice, moderated by Mark Williams and presented at Enjoy Contemporary Art Space in association with the exhibition Homing Instinct.

Dieneke Jansen is an artist, lecturer and social activist based in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. Working with documentary and social practices, Jansen's work engages with tensions between site-responsive interventions, performative actions and lens-based practices, and works with community to productively challenge inequality.

Heleyni Pratley is a Pōneke-based artist working in video, drawing, painting, sculpture, and performance to question the mechanics of value under capitalism. In addition to her art practice, Pratley campaigns for social change, having worked as an organiser for the Unite Union of hospitality workers. She is currently active in local housing and climate change movements and is a founding member of the Eye Gum music collective.

This conversation addressed the relationship between art and activism, with primary reference to several works: Heleyni Pratley’s 2022 public artwork A Work About The Housing Crisis With An Indoor–Outdoor Flow was presented with support from Urban Dream Brokerage and Letting Space in downtown Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, and comprised an open studio, discussion space and video projection. Dieneke Jansen’s extended engagement with the Tamaki Housing Group—a Glen Innes community organisation protesting the forced eviction of existing State Housing residents to make way for multi-use developments—has resulted in the exhibitions Areas A & B, Te Tuhi Offsite (2015); and 90 DAYS +, Te Tuhi (2018); recently, her practice has shifted focus to work with inner-city public housing tenants in Tāmaki Makaurau, with projects such as You’re Welcome, RM Gallery; Shadow’s Studio: Chatting with Scones; Artspace Aotearoa; and Backdoor-Doorbell Studio, Artspace Aotearoa (all 2022).

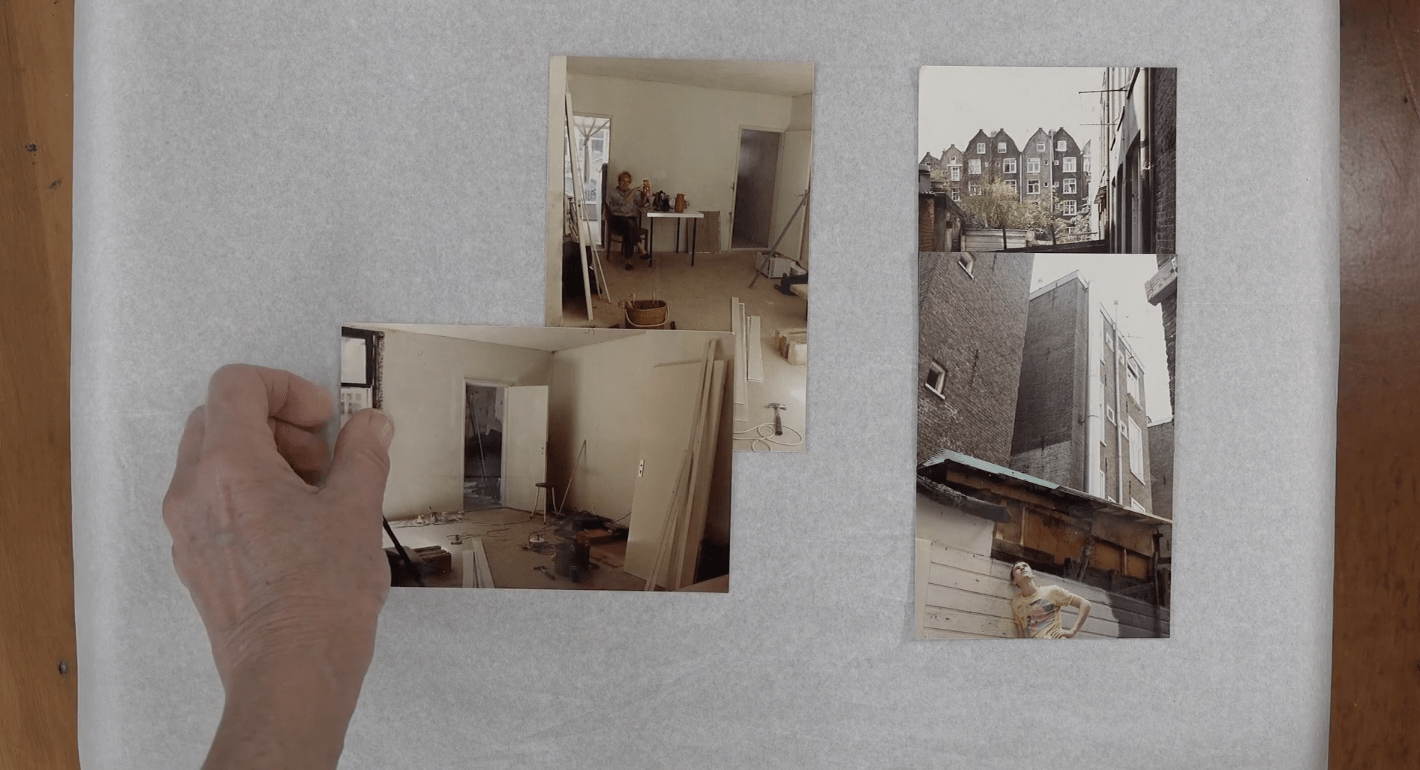

Dieneke Jansen, 90 DAYS +, 9th of June 2017. Image courtesy of the artist.

Mark Williams: Dieneke, in the course of your work with the Tamaki Housing Group, someone from that community asked you to document their eviction over a period of a year. In terms of working with a community from scratch, how do you begin and how do you get to that point of trust? And what's in it for them?

Dieneke Jansen: My time with the Tamaki Housing Group, which started before Niki [Ioela Rauti] asked me to document the process [of her eviction], was a really rich time of learning for me. It's about building those connections over time and asking what you are needed for, and then introducing some aspects of things you're doing that are more of an artist's practice in relation to that.

You arrive as a kind of lay person, part of the cause, and then you start to reveal a little bit about what you do. The very first thing I did when I met some of the Tamaki Housing Group was to express how outraged I’d been, when I'd just come back from a residency in Rotterdam in 2013, to learn that this [eviction process] was happening. So, I took a tent to an empty section in the neighbourhood, where a house had been lifted and just set up camp.

And the local wāhine came around and said, "What the heck?" (laughs) and I said, "Well, I'm outraged." And they then invited me to their weekly meetings, and you know, [today] I'm still referred to as that crazy bitch that turned up.

But it's a long learning [process] around finding the spaces of activism and art. And sometimes it's really just printing off posters or documenting buildings, and sometimes it's much more of an art-led thing, such as the projected screening on the back of a soon-to-be demolished house, which was a part of a project I did with Te Tuhi.(1) That sort of learning has helped me with the work I’m doing now with inner-city public housing tenants, because it comes back to a connection I had right back in 2012 with Radio NFA [No Fixed Abode, a homeless radio station], who were people in the inner-city community. So, it's iterative.

MW: And as the project goes along do you still kind of retain this position as 'the artist'—or do the people you work with become part of the artistic decision-making process?

DJ: Well, I think that's what's changed for me, which is cool, because it used to be much more like, I'll do it, and then I'll check. Working with Niki, I checked everything. And she [on one occasion said], "No, you have to leave that out," and I thought, "Oh I would never have picked that up." It was to do with respecting someone who passed away, and she didn't want to have footage of their house in the artwork. Those sort of learnings. Now it's much more of a collaborative project. I'm working with people and helping design aspects together.

Dieneke Jansen, Areas A & B (2015). Documentation of a community evening event organised for the local residents of East View Road in Glen Innes, at which Jansen projected the 1946 film Housing in New Zealand onto the wall of an old state house. Image courtesy of the artist.

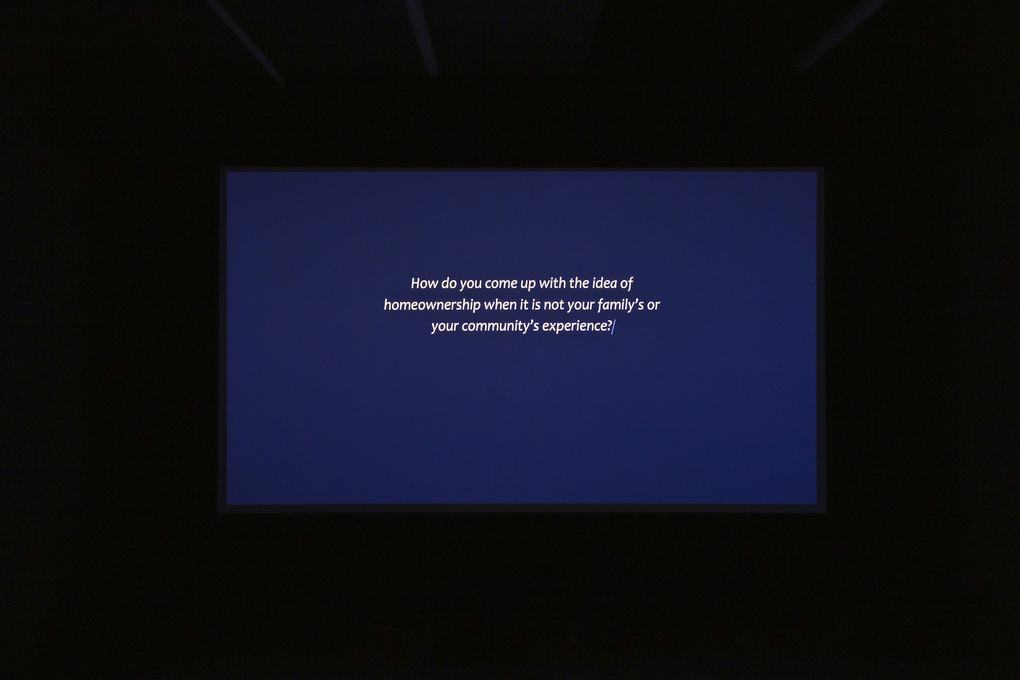

MW: Heleyni, I want to talk about A Work About the Housing Crisis with an Indoor–Outdoor Flow. So, this is a public sculpture where passers-by saw a series of white bubbles with projections on them of testimonials from people you spoke to. What was the process of inviting contributions from people for this work? You had a studio next to the actual exhibition site on Courtenay Place, is that correct?

Heleyni Pratley: So, I think it’s important to say I definitely see this work as part of a process. I was involved in setting up Housing Action Porirua and I feel like this project began with that activist work that started around six years ago. From there, I began Public Housing Futures with Action Station. This artwork came out of that activism.

I wanted to interview people [about their housing situation], and the 'Housing Crisis Community Reflection and Assessment Centre' is what I called the space where I would invite people in to talk with me. And it was sort of set up like a government department. I dressed smartly, I would invite people in, and I had tea and coffee. I worked for a number of years as a host at a museum, so it's one of my special powers (laughs). I'd show people pictures of the artwork and they could be interviewed for the work if they wanted to.

A lot of people knew about the project and came in from Porirua, or from around the places that knew me already, who had their own housing struggles. They'd book times to be interviewed or come into the centre. But a lot of people were just walking past, and that's really what I wanted as well. It was about it being sort of like a temperature check, seeing how people are really feeling about this [issue]. I interviewed all sorts of different people. It was interesting to find what the commonalities were.

So, I would interview people inside the centre, and then at night, an edited video reel of the conversations would be projected onto the Housing Bubble Sculpture, which was viewed outside on the street.

Heleyni Pratley speaks with people outside the 'Housing Crisis Community Reflection and Assessment Centre', part of A Work About The Housing Crisis With An Indoor–Outdoor Flow (2022), Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington. Image courtesy of Urban Dream Brokerage.

MW: Just getting back to that process, I mean, there's quite a contrast in the timelines; Dieneke pitched a tent and slept somewhere. You had people come visit, but you're also trying to nab someone as they're going past. What do you say to these people? What's your pitch?

HP: Sometimes I'd interview people on the street, but I had the centre set up so people would pop in. I'd say, "How's it going? I'm making an artwork about the housing crisis, I’m getting moments from people on video, if you feel like sharing anything with me, you can totally do that here." Usually, we’d have a really in-depth chat. One woman I interviewed for 10 minutes, and then we chatted and had coffee for about an hour afterwards—and that was not uncommon. I made sure people were comfortable and that I was clear about what this [project] was. And I kept in touch with a lot of people afterwards.

A lot of people who I met were having housing struggles—some I had met through my activist work—and who came in and wanted to be interviewed. The people that came up to me, or the people who came into the centre, they couldn’t wait to talk about it. Because we all know, I feel, we all know that something is very wrong. A lot of people were really relieved to talk to someone.

MW: Dieneke, when you show your works, what are you seeking to do? Are you trying to inform people, mobilise people, or maybe align with an organisation in your practice in some way?

DJ: So that's probably shifted over time, but definitely over the last couple of years, since I've been working with the inner-city housing community. I mean, to say 'community' is also a bit disingenuous, because that's in my head, but not in reality. We're talking about people who live in public housing in the inner-city area, of which there are quite a few. I'm interested in the relationship between these people and their immediate creative community, which is around Karangahape Road. And so connecting those spaces is also something that I'm interested in, because I'm thinking about the sense of the word 'publics'—and also the funding that goes into the different publics.

We all have this sense of governance, that we have democratic representation, that money gets spent on certain things that we share. But, you know, there is also that sort of cultural capital that allows someone to walk into a space of art. A lot of people are intimidated. And I’d suggest that the very people who don't have the financial means to go out to bars and golf courses have the greatest need for public spaces. The sense of the public that I'm really interested in is that connection. The projects that I've been doing have involved places like RM Gallery, which is an artist-run space, and Artspace, The Audio Foundation and the Old Folks Association, but also Kāinga Ora. Working there has made me realise that I really want to call the state in, rather than call them out, and celebrate those moments where they are upholding that responsibility.

There's a paper I read a while back by David Bates and Thomas Sharpie called 'Social Practice Strategies and Tactics'.(2) They write about how social practice over the last ten, fifteen years has filled in the role that the neoliberal world left behind, which is that care and provision for people. And social practice just took it up and did it. And so that's where I'm trying to pivot a little bit in my practice, yeah.

Heleyni Pratley, 'Housing Crisis Community Reflection and Assessment Centre', part of A Work About The Housing Crisis With An Indoor–Outdoor Flow (2022), Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington. Image courtesy of Urban Dream Brokerage.

Heleyni Pratley, Housing Bubble Sculpture (2022). Installation night view, A Work About The Housing Crisis With An Indoor–Outdoor Flow, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, 2022. Image courtesy of Urban Dream Brokerage.

MW: Heleyni, going back to that same work, how do you judge the efficacy of it? How do you quantify or qualify its outcomes?

HP: When I think about the work I engage in in the progressive political space, a lot of that can just be advising friends or working together on something. Maybe I'm not the face of something, but I'm still in that community. That work resonates with me. It requires you to be in touch with people. When I was a union organiser, I'd go into fast food restaurants and talk to maybe twenty fast food workers a day. I'd have a really good idea of where things were at, what people were struggling with. We rarely have those moments where someone says, "How are you? How are you doing, really?"

When you're an activist, and making artwork that is political, it's almost like a kind of processing. This artwork allowed me to go outside of this very insular activist space that was Public Housing Futures. Because of the pandemic we had been online a lot of the time, and there wasn’t a lot of face-to-face contact. So this artwork, I made it for me, in a lot of ways. But also for the community, and the activist community here in Poneke, to get a sense of where people were at. And when I met with people, if it was appropriate, I'd say, for example, there's things happening with Renters United—I would try and help people make links to other agencies that might be able to help them.

I live here, so I often see a lot of the people I interviewed and keep in touch with them. It's trying to form those links, and as cheesy as this might sound, I care, I'm concerned, we're all concerned, and what is to be done is something that we have to figure out together. What that artwork was about was how our agency is being taken away. Like our democratic involvement even with public infrastructure, we are quite disconnected, and people feel really quite powerless about that.

So, to answer your question, I see the role of art as being part of the process of shifting consciousness around a particular topic. And by asking people how they feel, it's saying, this is a conversation where your feelings are valid. There is something wrong here. And we have to try and do something about it. Putting the artwork in the central city, I felt, was like reflecting it back. It was a powerful gesture, because this is something that some people don't want to be visible. But here it is. It's visible.

MW: How would you rate the importance of the process of making the artwork versus the outcome? Would you say both are equally important?

DJ: I do. I think of it as both. Coming from a background that was preoccupied with expanding notions of documentary, questioning what that was, and looking at people like Barry Barclay in terms of the listening camera and thinking about looking alongside as opposed to looking at. Increasingly, I'm interested in the moment of making as being as valid as the outcome. But I also think the outcome is still really important. So it's not a social practice in the sense that we're together and we're doing this and we're done. I also have an attachment to this Hannah Arendt notion, ‘the space of appearance’, which is the point where politics plays itself out, where we listen to each other, and that's how we understand each other.

And that's why I'm so interested in that relationship between the publicly funded spaces of art and public housing. It's also about the capacity to inhabit those spaces so as to be visible, to be present, to be heard, but hopefully in a way that people have as much agency as they possibly can.

Dieneke Jansen, Backdoor-Doorbell Studio (2022), a community video-making studio within Artspace Aotearoa, 2022. Image courtesy of the artist.

MW: But do you think everybody in the gallery space more or less thinks the same way we do? We’re all on the same page. Is there a bit of an issue there?

DJ: I think that's a really good question. With my practice I open the door to people who don't go into those spaces, and I think that's a really interesting point of difference.

So making those spaces warm with manaakitanga. I had a project inside Artspace called Backdoor-Doorbell Studio, actually making on site, with people who had never made things before. You know, doing away with mastery, and this whole idea that you can only do this if you know what you're doing, and those sorts of things.

MW: I’m playing devil’s advocate.

DJ: (laughs) That’s all good. It’s the kind of questions we ask ourselves.

MW: Do you think audiences like activism in art?

HP: I think the service that art can provide is to invite people in. It's always nice when the work leaves a bit of a question. But then there are times when it's okay to say, this is really messed up, and this is a mirror, this is what we need to look at. So, there is a balance, but in my experience, I think there's nothing wrong with feeding our activist community as well as progressive art audiences. Here’s an artwork that's nourishing. So, it plays two roles. It gets people thinking, but also, sometimes maybe it is just for that community that you are working with on the housing crisis.

DJ: Lately I've been thinking that it's a little bit out favour, that it had its heyday around the big financial crash when the art world sort of took up the movement of the 99%, and this was housed in places such as documenta and Berlin Biennale in 2012. There was a real moment where there was a lot of discussion about how you couldn’t have art without politics. I feel that there's been a sort of backing away from that a little bit.

I think it’s also to do with how there's such a preoccupation with materiality and making right now. I see with teaching at an art school, there's a real return to hands on ceramics, there's a turn away from the screen, which is the screen that I'm also still really interested in. And I wonder if that's also about people needing to nourish themselves, because of the desperate state of the world we seem to be in at the moment.

Dieneke Jansen, This Housing Thing (2021). Installation view, Homing Instinct, Enjoy Contemporary Art Space, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, 2024. Photo by Cheska Brown.

MW: When a project ends, it's a culmination of a whole lot of energy, focus and excitement. How do you kind of carry on the political aims of the project after it ends? After it's uninstalled? Does it matter if it ends at that point? Does it mutate to something else?

DJ: When I did the work for the Jakarta Biennale, I'd reached a point where I was really questioning, who am I to be doing this work? I was there doing a project with people in the Marunda housing development, and the Biennale had come to Marunda, and at the time it felt really rewarding, but afterwards, already I was thinking, I didn't set people up to carry on doing anything. I didn't give them tools; I didn't open any doors. I was really quite critical of myself at that point.

The work I did with the Tamaki Housing Group was such a long protest that goes back to 2012 and finished in 2018. And everyone burnt out. People had passed away. There was a lot of hurt. For me, the artwork culminated in a show at Te Tuhi called 90 Days +. We’d done a whole number of things, including film screenings with a lot of other artists that showed around the country. But it had come to a point where there was no life in it left, and we just had to take care of ourselves.

I’m still in touch with some people. One person is quite interested in resuscitating some aspects of the group because she feels there are people who are on the street now who came from there. And I will help her if she wants me too.

The project I've been working on now since 2019 is much more of an iterative practice. People come and join, they drop away, they re-join, so it's never finished.

Installation view, Dieneke Jansen, 90 DAYS +, Te Tuhi, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, 2018. Photo by Sam Harnett.

MW: Heleyni, do you have any thoughts on that?

HP: This really speaks to how there's so much we don't know about how we connect as human beings. I don't mean to sound airy fairy, but I think activism and a lot of political spaces, they really take us away from the spiritual connections to one another that are unspoken. But you make a political artwork, it works in that mysterious space. And now it's over, I often feel like I need to do this [project] again. To see how things have changed or haven't changed. There's almost a little bit of a scientific approach to what I'm doing.

But I'm not sure. I know, though, through all my organising, that there is something [meaningful] about having a conversation with someone, and them having hopefully what is an uplifting experience—being involved in this artwork—and that stays with them and their consciousness does shift over time. So that's what this artwork's life is—it's that you don't know, but that's kind of the point, it's the process [that’s important]. And that's the same as in activism. Both are processes.

Homing Instinct is a collaborative international programme of artist commissions examining the human necessity for housing, shelter, and belonging, with works by Ari Angkasa (Australia), Dieneke Jansen (Aotearoa/Netherlands), Kahurangiariki Smith (Aotearoa), and Ananta Thitanat (Thailand). It is a partnership between CIRCUIT, Enjoy Contemporary Art Space (Pōneke), Composite (Naarm), Storage Art Space (Bangkok), and The Physics Room (Ōtautahi).