Campbell Patterson's latest solo exhibition at the relatively new Auckland artist-run space Fuzzyvibes reiterates many of the formal qualities of the work he presented for The network was desperate for new hits, an exhibition curated by Julia Lomas and Leah Mulgrew, and also featuring the work of Kah Bee Chow, at Dog Park in Christchurch at the start of this year. But while that show positioned itself as a close reading of the affective dimensions of serialised television viewing (see Amelia Bywater's incisive review for more on this), this newest exhibition, titled Watching, locates this experience more specifically in the domestic sphere.

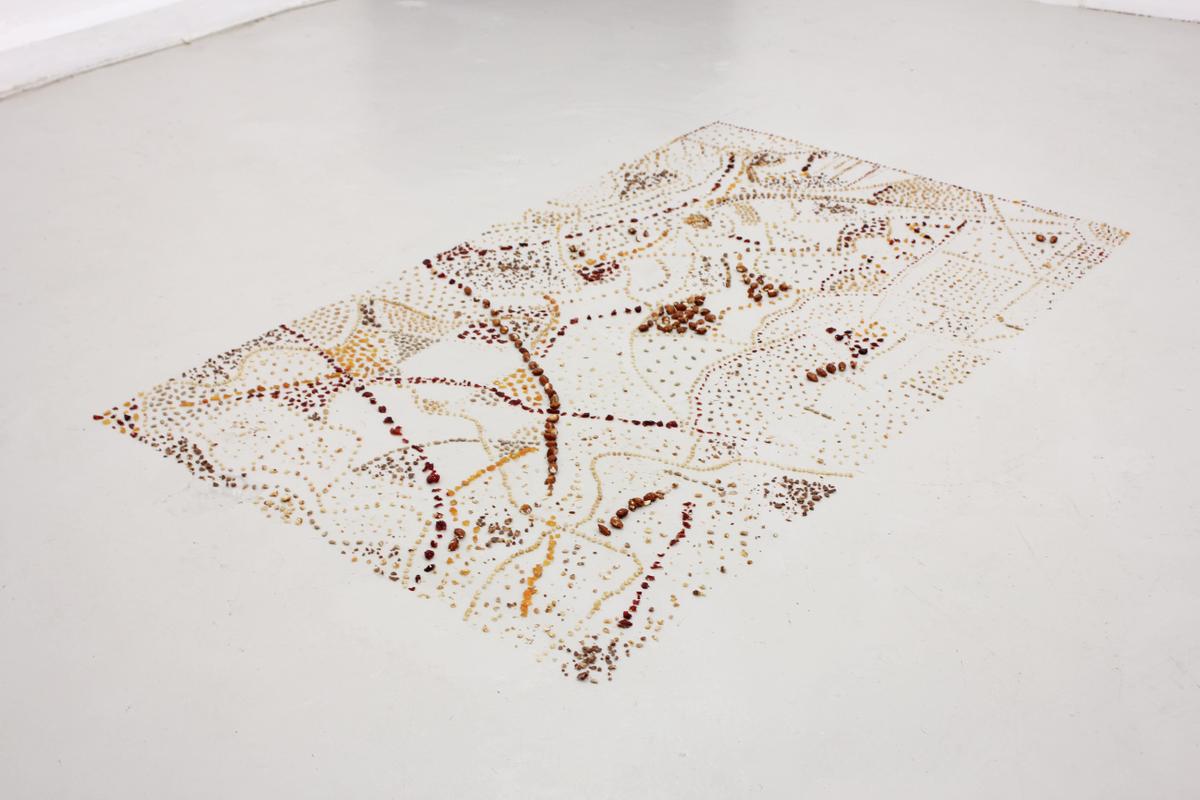

On the gallery floor are four rectangular works made using the deconstructed components of muesli bars. The various nuts, seeds and dried fruits are arranged in patterns of striking and elegant complexity, and while their placement on the floor is liable to make one think of rugs or carpet, the titles of the works suggest that instead we're meant to see them as couches. Reiterating Patterson's long-standing tendency to use materials from his own life within his art practice, the dimensions of these four works correspond to the dimensions of couches that have been owned by the artist or his family.

Installation view of Watching (2014) Campbell Patterson

Obsessively and painstakingly constructed, these muesli bar works speak to processes of revisiting and reconstructing that frequently surface in Patterson's wider body of work. A decidedly wholesome slice of childhood is literally deconstructed and compulsively reassembled by the artist in a seemingly futile gesture of vague personal significance. Standing in for couches that have inhabited the artist's domestic life, perhaps sitting in the lounge of his family home or first flat, these pieces take on a mournful quality that is made explicit in sadness couch (2014), which includes "tears" among its listed materials. They are abject too, easy to walk through and accidentally damage (in fact, at the opening, someone did just that) and their material components evokes the crumbs and detritus that might, say, fall between couch cushions. youth couch (2014) instills a further degree of ambiguity around the autobiographical function the work is meant to serve, with Patterson enlisting the gallery to formulate their own design for the piece. But rather than trivialising the work's personal significance, this collaborative gesture mirrors the role of autobiography in Patterson's wider practice, which tends not so much to provide the content for the work but delineates parameters within which fragments of selfhood may be tentatively reassembled.

The exhibition's melancholy treatment of domesticity is explored further in two video works that are displayed on TVs propped up vertically on the floor in diagonally opposite corners of the room. These two pieces, titled zopi 3&4 and zopi 5&6 (both 2014), consist of short fragments video taken from the recent sci-fi television show Under the Dome, which are looped between long stretches of suspenseful silence. This cut and paste strategy, assembling pieces of serialised television dramas, is familiar from Patterson's work in the Dog Park show. In that exhibition's Zopi 2 (2014), the artist edited together short excerpts from The Good Wife, cutting out the dialogue and frustrating both the show's and the viewer's desire for any semblance of narrative. His treatment of Under the Dome in these two new pieces performs a similar evacuation of narrative form, but goes one step further, dissecting the show's moments of narrative tension and redeploying them within the space of the gallery.

This obsessive, repetitive manipulation of source material has obvious parallels to Patterson's muesli bar pieces and bookending them with these two video pieces suggests a living room suspended in a dream-like state of endless dissection and reconstruction. Evoking a zoned-out, sitting in front of the tv kind of ennui, these works are also suggestive of the dedicated television watching schedules that have become especially prevalent of late as a corollary to the stressed out, strung out, insomnia ridden lives of the precarious creative labourer. The choice of television show hardly seems insignificant either, with Under the Dome's planetary scale drama—the show is about a transparent, impenetrable dome appearing with no explanation at all around a small town—resonating with the exhibition's own dynamics of enclosure, oscillating between warm security and a stifling sense of its own limitations. McKenzie Wark has recently suggested that the human confrontation with worldly limits of their own making is characteristic of a currently popular cinematic genre that he terms the Anthropocene. Moving dramatises such a confrontation on a reduced scale, reflecting an inevitable return to the domestic scene.

Installation view of Watching (2014) Campbell Patterson

The exhibition's final work, and one that is easy to overlook due to the connections between the other works in the show, is a plain sheet hanging on the wall onto which figures of cats are printed in black and stickers from apples have been stuck. Titled door cover (2014), the piece is an object that adorns Patterson's own bedroom door at home. But with its apple stickers that evoke school lunches, the work is the exhibition's suggests a link to the artist's childhood, and transplanted into the gallery is suggestive of the circuitous process of rediscovering, recompositing and recontextualising that has characterised Patterson's artistic practice and its relation to autobiography to date. Like his video performance series Lifting My Mother For As Long As I Can (2006-2011), in which—as the title suggests—the artist lifts his mother in his arms for as long as he can at the same time and place each year, the familial is here a site of ritualised return, an attachment that is in continual need of renegotiation.

Watching's placement at Fuzzyvibes is perhaps at first glance unusual—after all, it follows mere months on from a solo show at Patterson's main dealer gallery Michael Lett, Back in the World. However, while the presentation of that show was unusual to say the least, consisting of one sole video and a large number of small, unassuming paintings propped up against the pillars of that cavernous space, Watching is remarkably concise. This is a welcome change of pace for an exhibition space that since opening in February has arguably struggled to find its footing, with a few too many unwieldy group shows interspersed with a couple of gems, such as Michael Lee's Lead Singer. With its submissions-based exhibition model, Fuzzyvibes can sit awkwardly between being a community-driven space and being shaped by the artistic and curatorial impulses of its directors. That Fuzzyvibes opened with an exhibition examining the legacy of artist-run spaces in Auckland suggests a healthy awareness of the significant role that spaces such as Gambia Castle, Snakepit or the now virtually deified Teststrip have played in shaping the current Auckland art ecology for young artists, perhaps now it's a question of stepping out from under these spaces' considerable shadows.

In lieu of providing something entirely unexpected, Watching suggests Fuzzyvibes may be moving into a more cohesive body of shows, with the exhibition consolidating Patterson's longstanding interest in video as a medium—long an integral, if peripheral element of his practice—in relation to his more recent treatment of serialised television as subject matter. The fragmentary bursts of video and sound from the two zopi works that intermittently punctuate the gallery suggest a televisual lifeworld that in its conventionality is no less significant to the ongoing making and remaking of the contemporary subject than one's personal effects. That this process is fraught with digressions, diversions and endless reruns should come as no surprise; this is the kind of inertia that will be familiar to anyone whose primary weeknight activity is binge watching tv on their laptop before passing out.