Comprised of four moving image installations and a large text work, Marianna Simnett’s CREATURE is a vaulting reckoning with personal and historical trauma. Using myth, magic and medicine, she fearlessly seeks to image psychological and bodily horror, which achieves shrill resonance through its impact on the vulnerable, and Simnett herself. The gamble of the work lies in the delicate balance between compelling the viewer to look, whilst simultaneously repelling our gaze. How then, to draw the viewer into a world that also pushes us away?

In the popular nineteenth-century century nursery rhyme "Ring-a-round the Rosie", the children dance, sing "A-tishoo", and in giddy unison proclaim "We all fall down!" While children today revel in the song’s chant-melody and mock faint, some have tied its origins to the Black Plague, a devastating global epidemic that struck Europe and Asia in the mid-1300s, killing millions. In one disputed but wide-eyed interpretation of the song, the "ring" is a red circular rash, the "A-tishoo!" sneeze as the tell-tale sign of disease, and "falling down" was to die.

Whether true or not, Simnett's CREATURE trades on such mythical origin stories, and likewise, juxtapositions of naiveté and cruelty. In particular, children and animals are undone by their vulnerability, lacking bodily and psychological safeguards. And just as the plague most certainly did reveal itself through the body, Simnett scans for the tell-tale signs of distress: of systems brutally impacted, distorted, failed; or even the quiet banality of things simply not working as they ought to, yet building surely to a hideous eruption. At the same time, CREATURE is no simple imaging of trauma.

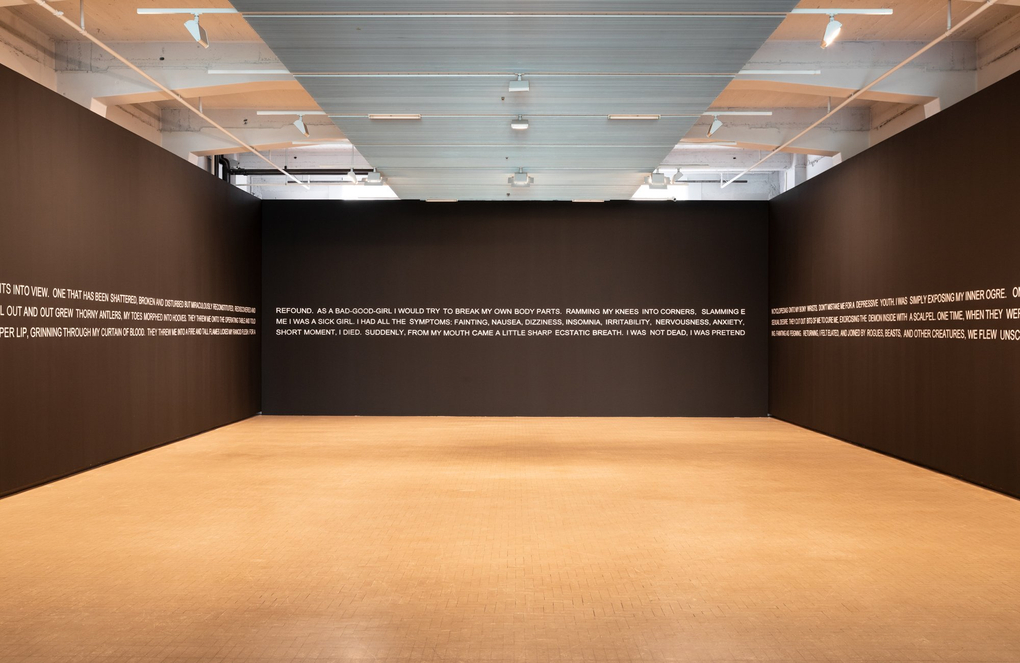

CREATURE’s first work is encountered immediately upon entering City Gallery, a text work in block white capitals that wraps around three walls of the gallery’s expansive foyer, an immersive void. If the show is called CREATURE, then perhaps this is the Creation Myth:

CRĒTŪRA. CRĒARE. CREATE. A NEW CREATURE ORBITS INTO VIEW. ONE THAT HAS BEEN SHATTERED, BROKEN AND DISTURBED BUT MIRACULOUSLY RECONSTITUTED.

Installation view of CREATURE, Marianna Simnett, City Gallery Wellington, 2021.

Hovering on a black, almost chalkboard background, the text describes a brutal dismemberment and rebirth. But here Simnett taking an Earth-defying leap into another realm, and an emancipatory rush beyond all human limit:

I CUT OFF MY ARMS AND IN THEIR PLACE GREW WINGS, MY HAIR FELL OUT AND OUT GREW THORNY ANTLERS, MY TOES MORPHED INTO HOOVES... I FELT ELATED, AND JOINED BY ROGUES, BEASTS AND OTHER CREATURES, WE FLEW UNSCATHED THROUGH THE STILL BURNING FIRE

Each line continues breathlessly across the three walls in an unbroken narrative. This is a simple but important installation strategy by Simnett. In turning back on our heel to read the next line, whilst striving to maintain the thread of the previous text—and orientate ourselves amongst the clamour of the all-caps text—we immediately start to feel our own sense of displacement, a key theme of the show invoked bodily in the viewer.

In the gallery next door, Blood in my Milk (2018) is a five-screen installation whose screens fringe the edges of a sprawling red carpet. Like the text work, we’re invited to watch from the centre, where the bean bags underneath us will soon come to suggest blood clots.

Installation view of Blood in My Milk (2018) Marianna Simnett, in CREATURE, City Gallery Wellington, 2021

Blood in my Milk follows the girl through a number of scenes: on a dairy farm; having surgery to remove a bone in her nose; post-operative recovery in a larval-like sleeping bag; and a journey to a laboratory, where the "grown-up" Marianna (played by Simnett herself) walks the hallways like Alice through the looking glass. There is an obsession with the semiotics of institutional and extractive processes, from the banal recounting of dairy milking methodologies to the intravenous administration of anaesthetic—“Little scratch… you'll just feel a little cold…” and in the background we glimpse the logo of the hospital equipment manufacturer. Operating on a sliding scale between matter-of-fact documentary and fantasy, the installation abounds with sing-song melodies, full of childhood rhyme, but speaking a deranged libretto of mastitis and chastity. In these jarring juxtapositions we sense a process of bodily dissociation and female disempowerment, something which is equally enacted on an insidious psychological level. As Simnett's voice-over says, “I should never have crossed my legs...I was the good bad girl”

Nothing about the Blood in My Milk is less than challenging, from its graphic images, to the staged vulnerability of children and animals, which sinks into your stomach with the queasy foreboding of things-to-come. Likewise, its 73 minute length is difficult, and the multiple perspectives across multiple screens—although each screen offers predominantly subtle takes on the primary action.

The work follows a young, blond pre-pubescent girl through to what might be assumed her metamorphosis as a young woman. In this trajectory, Blood in My Milk is a structural mirror of the text work, but looped; suggesting a cycle of generational female experience stuck on repeat.

Installation view of Blood in My Milk (2018) Marianna Simnett, in CREATURE, City Gallery Wellington, 2021

Most of Simnett’s male subjects are pre-pubescent and teenage boys, either at play or waiting for medical treatment. The adult men are subtly disempowered by bodily function, from a doctor with a boil on his neck to a hearing-impaired farmer who struggles to communicate easily, relying on accompanying his voice with sign language. Despite these bodily "tells" on some of the males, Simnett maintains an ambiguous portrait of who the potential abuser might be, cleverly refusing agency by not centring them in her story.

Instead, Simnett’s survival strategy is to examine trauma's cooled, black, liquid residue, morphing the after-image into something new and darkly inhabited. We’ve seen something similar before at City Gallery, in Jono Rotman’s 2015 installation Mongrel Mob Portraits. A series of ultra-large format photographs of gang members, each clad in patched black leather, their faces etched with scars, inked affiliations and facing the camera with stoic intensity. Like Simnett’s subjects, these photos traded on the dual pivot of projecting an image that is both challenging on the surface, but also on the deeper level of imaging trauma and dispossession, in this case, from colonisation. But again, like Simnett, each of the subjects in Rotman’s photographs embody a new sense of personhood. The challenge raised by both Simnett and Rotman to us, is not just to see, but to feel what trauma looks like. Likewise, both artists imply a critique of the gentrification of trauma through media. If anyone visiting the show has issues with Simnett’s eviscerating images, and the bodily recoil they induce, then consider just how numb we have become to the daily news cycle of death, neglect and needless human suffering.

CREATURE was previously exhibited at Brisbane’s Institute of Modern Art (IMA). It comes on the back of an ever growing profile for the Berlin-based artist, whose work has been seen in galleries across Europe. Simnett is not only adept across multiple registers of moving image, but also works in drawing and sculpture, and her work in Creature extends on early training in musical theatre.

The City Gallery edition extends the IMA show further with the inclusion of the looping short film The Bird Game (2019), an addition that pointedly suggests some of the traumatic origins of the works in CREATURE.

The film begins with a group of children sleeping on a lawn, who are visited by a talking crow, rousing them from a fitful slumber of fearful dreams. The crow proposes a magical game: “The prize is pretty delicious... what is it? You will never need to sleep again. Let's play!”

Installation view of The Bird Game (2017) Marianna Simnett, in CREATURE, City Gallery Wellington, 2021

Like the abandoned children of Golding's novel The Lord of the Flies (1954), "The Little Beasts" run giddily through the grounds of a grand manor, entering its gilded walls through doors which thud shut behind them. Once inside, the children's clothes transform subtly into costumes of princes, princesses, a knight and ladies of the court. As one lies prostrate on a satin bed, the crow narrates a once-upon-a time story of “...girl... a beautiful princess, who lived in a house where a cold hearted witch hexed her ...only a kiss could wake her...”

From there, the children proceed to blindly follow the crow's every invitation, with horror results: they kiss the princess and her skin blisters, they dance and sweat blood, the crow rips out the child’s eye and nibbles at it; later, in the bath, the children drink a teaspoon of liquid and sink into a slow-drowning stupor.

More nightmares follow, including the crow's suggestion to the final boy that he drop his pants, play with it and “gasp for me.” Finally, one girl remains, her face riven by a plague-like sheen of jaundice. This is the cue for the crow, in her hoarse, grand-matronly voice to declare “I was once a girl like you,” and narrate her own traumatic transformation from young girl to crow/creature. As with the evolving character in Blood in My Milk, this suggests a generational violence that re-enacts itself time and again, but in this work it extends to a third generation, enough for us to consider it a cycle of history. In fulfillment of the crow’s reward prophecy of never having to sleep again, the girl throws herself out the window.

Throughout CREATURE there are subtly different approaches to installation that build on the opening text work’s strategy to provoke the viewer’s bodily engagement with the work, and dislocate what we idealise as an image, or model behaviour. The two remaining works in the show hark back to histories of performance art, where the (usually male) artist subjected themselves to endurance based tests of the body’s limits, but also more contemporary female artists such as French artist Orlan, who augmented her physical self through surgical intervention, in part as a way to address the ideal image of femininity as seen in art history.

Still from The Needle and the Larynx (2016) Marianna Simnett. Courtesy of the artist and Serpentine Galleries, London

In The Needle and the Larynx (2016), Simnett receives a botox injection to her throat. (We see this also in Blood in My Milk, where a doctor denies her request, telling her it’s only a treatment given to boys to lower their voice. Here, Simnett simply takes the dose.) Perhaps this is the most confronting work in the show, a single projection of Simnett’s aqualine neck: the application of the sterilising gauze, Simnett’s ready vulnerability, the precise injection. And then, Simnett’s post-injection smile, as if, indeed, sampling something "pretty delicious!"

In Faint with Light (2016) Simnett hyperventilates to the point of passing out. We hear her harsh, rasping breaths, while on screen we see nothing but brutal black and white horizontal bars, which strobe and flash in sync with the volume. The work is based on a story about her grandfather fainting in front of a World War Two firing squad, thus avoiding death. Here, at the point of passing out Simnett lets out a shrieking howl, a sound that Simnett has apparently never heard herself in the moment of fainting.

Installation view of Faint with Light (2016) Marianna Simnett, LEDs, audio, aluminium, acrylic, sound, in CREATURE, City Gallery Wellington (2021)

Faint with Light is stationed just behind Blood in My Milk. When seen directly the image is all encompassing, when heard in the background of the gallery, its peak exclamation sounds out behind us, as if signalling some buried psychological scar. Meanwhile, The Needle and the Larynx is the sole work in a large gallery space. The attendant waits by the entrance, and from there the distance to the centre is just long enough to ensure that many will feel obliged to spend time with the daunting image. Longer, perhaps, than they might have otherwise.

On the publicity image for the show it’s not clear whether Simnett is spitting something out or swallowing it. Her eyebrows are dark, her hair dyed blonde, her eyes blue/green—she could be a cyborg. But it’s in the conclusion to The Needle and the Larynx that we grasp the essential human-ness at the heart of Simnett’s work, where two days after the botox treatment, Simnett hoarsely describes the experience and after effects: "It felt like someone was holding my throat from behind… They didn’t tell me I was going to feel so weakened by it..." Likewise, after watching The Needle and the Larynx, the text work in the foyer no longer looms as creation myth but a moment of personal disassociation, brought about by historical trauma inflicted on women's bodies and psyches. And if we look close, the block caps give way to hints of the weary copywriter; a gap too far between the hand-printed letters, the raised bumps of their painted surface.

Ultimately, any such weariness yields to Simnett’s determination to confront her experience of the world as a youth and as a woman; to image its sweet but treacherous falsehoods, to re-claim fantastical means as material for re-establishing a solid foundation in the world.

But, returning to an earlier point about images, exiting Creature is also an experience of sensory renewal and awareness. It’s there in the details, from the overhead hum of City Gallery’s air conditioning, to the subtle architecture of sanitation, gender and self-image in the bathrooms. The silent purpose of all things, working its magic.