Raqi Syed: What brought you to animation?

Tanu Gago: My whole life I’ve been enamoured by animation. Because it stems from the imagination, it became a way to interpolate reality. I’ve been attracted to it since I was a child, watching cartoons in the nineties. I went to Freelance Animation School but I didn’t last long. You have to be super disciplined; I was young and impatient.

I brought commercial film and narrative-based skills into fine art which isn’t common practice. Art can be nonlinear—you can really deconstruct the form and the genre. In tertiary fine art education in New Zealand, you’re often told to lean into your culture, that this will help you navigate what stories to tell. At the time I didn’t know what that meant, I had to get some life experience first.

I came back to linear narrative storytelling in filmmaking and photography. There was a form of cultural framing about how you tell a story in a still image. I’m slowly coming back to my passion for animation. The tools have become incredibly powerful, computers can do a lot for you now.

RS I started making animation in high school. We replicated simple structures, like a beginning, middle, and an end. We were told an animated film is a good story well told. That put me on a path I’ve almost never deviated from—which is that animation is fun. It’s powerful, it’s direct, it’s complex.

When I worked at Disney Feature Animation Studios a lot of it was about repetition, this fixation on the pixel – not only do you care about one twenty-fourth of a second, but you have to care about the pixel. If there’s one dead pixel, you could spend your whole day fixing that.

TS I think that’s what most animators have in common, that obsessive attention to detail. That margin of interpretation as a singular pixel can be redefined. How you interpret a piece of motion, or the way an emotion is translated through a story. That extra five frames makes a difference, in terms of breathing room for the story, or saying something about a character.

Film school filled in so many gaps that I wasn’t learning through animation school, because there I was being groomed for the industrial complex of animation. I was more hungry for learning how to tell a story.

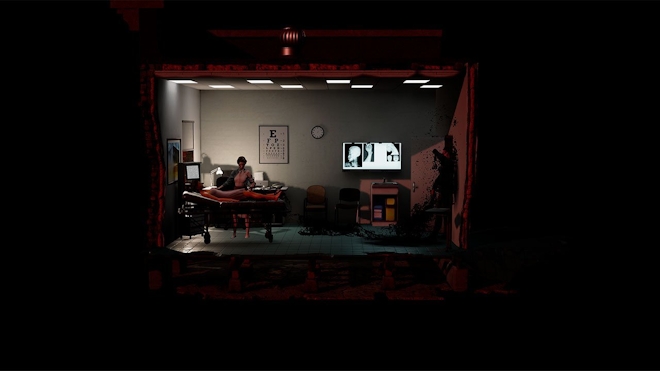

Tanu Gago, still from Coven Aucoin (2022). Animated video, sound. 3 min 16 sec.

RS There’s a disconnect—as a student, you have to do a lot of things, it’s an enormous learning curve, and as a professional in the industry of big budget or commercial animation, you do only one thing and become really good at it. I specialised in lighting characters—not lighting environments, effects, or water, but specifically characters.

Once you go back to being an independent artist, you have to learn a lot of things again. You have to decide what kind of animator you want to be, how you want to use animation. Animation has this massive context of cinema and storytelling. If you can put it in this interdisciplinary context, it’s easier to understand what you’re trying to achieve.

TG It has the same fascinating qualities of cinema in that it’s a composite art form. You are drawing from other mediums and genres of work, whether it’s sound design or a series of reference materials, and where those comes from – whether it sits within the cultural consciousness, or you pull it from the internet. There’s a history that comes before the moment you are trying to compose something. You will always have a reference point.

At animation school I was encouraged to tell my story, and I just didn’t know who I was—I don’t think I was out at the time. If you don’t know what your story is, it’s hard to find the visual language, the voice to compile everything. To know what I wanted to talk about, that took some time.

RS The film school I went to was started and run by queer feminists. I thought that’s how the animation world was run. When I went into the industry, I realised that’s not what animation was.

Salman Rushdie’s writing was really important to me as a young person. Literary science fiction was where I first learned people who come from the same place my family comes from—India, Pakistan and South Asia—can tell speculative stories about their own history. It’s really hard to do—Rushdie says if you don’t know who you are, you cannot write a story. That’s what’s tricky about identity politics or the formation of identity. Having some life experience, then coming to the critical aspect of the formation of identity—if you do it in that order, it feels easier to build an art practice around it.

This thing where you go to art school or university and some white person tells you you must access your identity, this place you came from, so you have something unique to say—it’s prescribed; that in and of itself becomes a eurocentric violence. I have to justify being in this room by being a person of colour, who’s going to talk about being a person of colour. It’s like I don’t have the privilege of just talking about genre or being a person in the world.

TG It’s been absorbed into that framework of academia. It sounds cliché, but those prescribed steps are your method of unlocking your worldview. I’ve been in so many instances, whether a writing room or a creative brainstorming space, where there’s freedom to probe at other cultures purely as a thought exercise. For non-Indigenous people, that’s such a luxury. People of colour are extremely mindful about the parameters of what that looks like, of the way we reference those things. I do find that challenging. It can be a double-edged sword. I think there is a way to move seamlessly through the politics of identity without it becoming a trope, or a barrier or burden.

Installation view: Otherwise-image-worlds (4 June—4 September 2022), Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. Courtesy of the artists and Te Uru. Photo by Sam Hartnett.

RS At SIGGRAPH, a computer graphics conference, we talked about diversity and what it means in a technical context for making computer graphics—both from a research perspective and the visualisation of culture. It’s uncomfortable for people, but one thing we agreed on was that there’s no one solution. We have to do a lot of things, many of them messy, and they will yield different results. Allowing ourselves to be in this messy place is difficult, but it’s a better way forward—it invites more people into the discussion. Politics is so polarising because people don’t know how to proceed. For me, the story is going in the right direction if I start to feel uncomfortable.

TG If you shift to an abundance mindset, it’s adding more dynamic range to your conversation as opposed to asking, if we have this, what are we losing? Why can’t we have them all? Even the ones that are wrong? Let’s put everything on the table. It should make you uncomfortable, it should be messy.

RS I’ve been thinking about moving to a labour-oriented framework for talking about my art practice—essentially a Marxist politics, rather than identity politics. Animation is good for that. The history of commercial animation has been tightly bound up in the organisation of labour. Even the biggest animation studios in the world like Disney and DreamWorks—they’re union shops.

Disney was one of the first places I worked, and it gave me a mindset about the transparency of pay and the accountability of organisations to the politics of labour. From a global perspective, we’re now seeing people engaging in discussions about the value of labour. If we can do that, we invite more people into the discussion. That’s what needs to happen, because capitalism keeps chipping away at the value of our labour, particularly art labour.

Still from ATUA (2022), written and directed by Tanu Gago, created by FAFSWAG, produced by PIKI Films, digital creative direction by Wrestler. Augmented reality experience. Courtesy of the artist.

TG That is the line I’m always treading as an animator, to find this middle ground between my hybrid set of skills in animation, photography, and ethnographic and cultural-based storytelling, and what the art world expects of you as an artist, which is to have a response to the state of the world or your environment. I often draw from spaces in my community to figure that out, and utilise animation as a way of amplifying those conversations and putting them in the public domain for people to have their own interactions with it.

RS For ATUA VR, what was the process of working in a new medium like? You had to enter into a world of collaboration with tech people and design people—new and different spaces.

TG ATUA was a 2017 project by FAFSWAG, a VR experience that took you to Pulotu, our underworld where Pacific gods and deities exist. In 2017, members of our collective were engaged in performance practice, activation, and part of that was drawing on essential knowledge and talking to the va, which is the sacred space between all beings and all things, identified as active, not dormant. We were part of a handful of artists around Tāmaki Makaurau and Aotearoa at the time who were practising this form of performance. We were invited to activate a lot of public art spaces and create rituals.

At a hui where collectives were invited to participate, we did individual performances. We were culturally in a totally different realm – there was a vibration at that time, and one exhibition where artists were drawing on ancestral knowledge. We were part of a frequency that didn’t seem like natural reality. I remember coming home and writing a treatment about reproducing that feeling but in a museum context—a VR exhibition where you’d see these activations articulated for a digital experience, a code-based interaction with motion capture and a reinterpretation of those cultural performances.

We rewrote the treatment as a sculptural augmented reality experience where I’d pick a singular deity and tell a story about it, one beat at a time. The first beat was Tangaroa, the god of the ocean. It grew into a project with my producers at Piki Films about the atua, spread across a series of physical pouwhenua. When you engaged with them through handheld devices, they’d generate a digital version of a deity.

The artist I asked to perform Tangaroa said they were nonbinary and wouldn’t feel comfortable being Tangaroa, so I asked them to pick a deity on the spectrum and they chose Te Kore. Te Kore is traditionally perceived in Māori culture as a space as opposed to a physical, celestial being, so it was quite controversial to give them a body. We took about a year to get cultural advice—we spoke to a lot of Māori arts practitioners and elders. We also had conversations about licensing and IP, and whether we all have access to these stories.

Still from Tanu Gago, SAVAGE IN THE GARDEN (2019). HD video. 4 min 51 sec. Courtesy of the artist.

RS People should be allowed to explore these stories, but the process is important—how you arrive at the story, who is involved. Who is invited to access the story?

TG The deities were part of our existing practice, things we’d explored and talked about for years. If you look at our practice over the last ten years, there’s a clear trajectory to these cultural figures. A lot of our formative work is imbued by the same spirits, mana, of these kinds of cultural conversations. The one thing we didn’t want to do was to create a precedent for those characters to be licensed. That took time to figure out—being mindful we weren’t doing things in a way that was exclusive.

RS We could think of it as open source—making the method and process available so that others can use it to arrive at their own results. The method is important too. Metahuman, for example, the character creator platform—it’s so powerful and sophisticated. But just because you can push a few buttons and make a good looking character, does that mean you should without a method attached? Why does this character exist? What is the character doing? Who is this character based on? Then you use the tools, and when you put those things together, you can do amazing things. What I find frustrating is that these powerful tools often do not have methodology that sits next to them.

TG The moral, ethical boundaries of what is possible haven’t been defined. There are layers upon layers of protocol. We tried to steer away from being definitive about whose culture it was. We were mindful to talk about restoring LGBTQ identity to the realm of our mythology, because it’s been erased through colonisation and the first contact with Christian missionaries in the Pacific. That is still the ultimate goal—to create narratives that feel restorative and insert us back into our mythology. Recognising that as our agenda for the project gave it direction in terms of what we could talk about, and what wasn’t for us to talk about.

RS Virtual reality or extended reality is a good medium for that—if you put on the headset and move around, there’s an embodied element. That embodiment necessitates questions around who is doing this and why, and opens up that discussion in a way that non-spatialised mediums can only do indirectly.

TG That element almost mirrors the ritual in the real world, because that activation is an embodied practice. Artists occupy space with their physical being, but they’re expanding the space based on the ritual they’re performing. That’s what I appreciated about augmented reality—the device makes you participate, makes you complicit in a series of actions. Or it made you integral to the story in the way you’d feel if you’d experienced it in the museum.

RS That’s why I love VR, it’s one of the few mediums that you can’t second screen. You have to fully engage in it. We used to experience that power with cinema—back when people had to go to the movie theatre, sit down in a darkened space with the curtain in front of the screen. Cinema was supposed to be a religious experience, like you’re at the altar. It used to be this transformative experience that people would go to, and emerge from it changed.

TG In Tonga I would wag school and go to the cinema. You could stay the whole day watching films because the tickets were for three movies. I spent most of my time as a child in the cinema by myself, I remember feeling swallowed by the experience. There’s an orientation process before diving in, and then coming out suddenly in the real world. That process is important to that experience – everything is a memory, it’s part of building your nostalgia or your recollection of things.

RS Emerging out of virtual reality has that same feeling. The Australian queer feminist artist Kathy Smith teaches a class at the University of Southern California called Expanded Animation which was formative for me. She made us read Freud and talk about animation and virtual reality as ways to access dreams.

We can call the virtual reality space the ‘volume’. It’s blackness, which things emerge out of through an additive process. If you treat the volume as negative space, it’s dream space, consciousness. You don’t have to justify things or do the prescriptive thing in television or film—the establishing shot of the house, then the door, and then someone walks into it. You don’t even need the door—you could just have the sound of the door, and someone walking into the space.

TG There’s something beautifully cognitive about VR. It feels like an extension of how you experience the world, as opposed to the illusion of cinema, which I feel is constantly manipulating your perspective whether through cinematography, editing or sound design. There are aspects of VR that I find quite terrifying – the volume, the darkness, the way things emerge and fluctuate, the purpose for things. Sometimes I feel like I’ve shrunk, and there’s a massive tidal wave coming.

RS I think the language of virtual reality is scale. The language of cinema is the cut, the camera, the framing. Since we don’t have that in VR we wanted to play with it in MINIMUM MASS, which unfolds as a miniature diorama. Then it cuts to these room-scale embodied moments. Scale is the visual language; we played with it to make things miniature or really large. We’ve only scratched the surface in terms of what you can do with scale in storytelling and how it becomes part of the narrative.

TG That was an aspect of ATUA I was attracted to in terms of medium. VR enabled scale. Your atua should be massive; that was something that I appreciated about the way that digital bodies were perceived in science fiction like Blade Runner. What could the Pacific version of this manifested digital future look like? Will projects like this add to that canon of storytelling? For us it’s rooted in a cultural practice; there’s a different layer of meaning. But for people who don’t have the same cultural framework, it’s science fiction, it’s the same type of make-believe dreaming space as filmmaking.

Still from Raqi Syed, MINIMUM MASS (2020). Interactive narrative virtual reality. 20 min. Courtesy of Like Amber.

RS It’s the interplay between the accessibility of mono-myths, these large mythical forms that cut across different cultures, and something specific and gritty related to your lived experience. If it goes too much in either direction, it becomes generic or insular. It’s the interplay between the two that is truthful and interesting, and invites people into the storytelling process.

With MINIMUM MASS, we wanted to tell this heavy, personal story about miscarriage. The speculative lens became the wrapper around which this story became accessible to more people. It’s a way for you to insulate yourself too, because it’s a lot of emotional labour to talk about your personal story. It becomes easier If you frame it through the lens of genre.

TG That’s what I love about these art forms, they can articulate something that you can’t always express in words. I’m into the idea of replicating reality, to look at it as a mirror, through a lens of Indigenous masculinity. There’s a cultural stereotype, a binary that Polynesian men are often situated in: either the virile, exotic other, or dangerous and volatile.

There are so many other aspects of our Indigenous identity. I want to know how these things will exist in this future digital environment, and how we shift the paradigm before that happens in relation to the Indigenous or Polynesian experience. There might still be time for us to figure out what that looks like before we reproduce ourselves in this way.

RS One outcome I want to see consistently is the value of the labour of artwork. Technology enables productivity and access, but there’s still the entire conceptual and craft framework around it that is contrary to live-action. You get nothing for free in animation, everything must be deliberately crafted and constructed.

TG Animation is tapping almost directly into the imagination as it’s being created and manifested. It’s quite incredible—it’s not like in film, where a set of practical components have to happen before a shot can be established. I’ve been in love with animation since I was a kid, and I say I get bored of drawing, but all I ever want to do is draw.

The exhibition Otherwise-image-worlds was on view at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery from 4 June to 4 September 2022. It was developed in partnership with Te Uru, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland and curated by Tendai Mutambu. Supported by Creative New Zealand Arts Council of New Zealand Toi Aotearoa.

Interview republished from the Otherwise Worlding reader, published by CIRCUIT Artist Moving Image (2023).

Tanu Gago is an interdisciplinary artist, Queer activist and filmmaker. Working across film, digital arts, animation and interactive technologies, Gago aims to build restorative narratives of Queer Indigenous Moana experiences. He was a McCahon House artist in residence in 2022, and is currently an artist in development with Piki Films. Gago is co-founder and creative director of Queer Indigenous arts collective FAFSWAG, who represented Aotearoa at documenta fifteen (2022).

Raqi Syed is a technical artist, filmmaker, writer and researcher with a background in studio animation. Her practice explores the materiality of light, hybrid forms of non-fiction and genre storytelling, and an anti-racist critical aesthetics of visual effects. She is a 2018 Sundance and Turner Fellow, and a 2020 Ucross Fellow. Syed teaches at Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington.