In here, space is soft. Like blocking a lightbulb with your fingers, the walls betray an illuminated, epidermal glow. A low hum thrums from a nearby fan. In here, there are no words, no signs of any kind – just the body and space.

Bailee Lobb’s Orange Cathedral (2021) is a large, interactive, orb-like inflatable in the entrance of Who can think, what can think, an exhibition at Te Tuhi, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland that seeks to challenge definitions of intelligence by embracing historically othered modes of cognition, centring its focus on neurodiversity in humans as well as animal, plant, and machine thinking. The exhibition offers a comprehensive, research-based exposition of neurodiversity—including a breadth of media spanning Lobb’s inflatables, speculative video works, and explanatory, wall-based diagrams—which is paired with a multi-modal exhibition design intended to cater to a broad range of information processing differences.

.-Photo-by-Sam-Harnett.jpg)

Bailee Lobb, Pineapple Place in Yellow Space (2021), installation view. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Examining historical designations of intelligence and how they have marginalised neurodivergence among humans as much as non-human entities, Who can think, what can think is structured around three parts: the networked intelligence of plants and non-human animals; historical classifications of cognition and their relationship to the entangled histories of colonisation, institutional abuse, and environmental degradation; and current discriminatory systems as well as emancipatory approaches to counter them.(1)

Accompanying this focus on socio-historical context is the close attention paid to Who can think, what can think’s exhibition design, which was developed in consultation with Neuk Collective, a neurodivergent artist collective based in Scotland. Greeting the viewer at the entrance of the exhibition is a broad range of interpretive guides that supplement what we have come to expect as the standard exegetic material of art exhibitions. In addition to the small exhibition reader (which, according to Te Tuhi’s existing accessibility guidelines, is printed in dyslexic-friendly text), there is the same exhibition text available in large-print, Easy Read, braille, and New Zealand Sign Language video formats, as well as a number of reading aids. In place of wall labels, artwork information is provided in the form of an A4 sheet of paper designed to be lifted off the wall and carried, with QR codes at the bottom of the text that provide access to an audio description and transcripts for screen readers. As well as these textual guides, Te Tuhi also provides ear defenders and communication badges in the form of coloured lanyards that indicate whether the person wearing them is happy to be approached.

-access-wall.-Curated-by-Bruce-E.-Phillips.-Photo-by-Sam-Hartnett.jpg)

Installation view of Who can think, what can think access wall, Te Tuhi (2023). Curated by Bruce E. Phillips. Photo: Sam Hartnett

In some cases, there is a slippage between the components of the exhibition design and those designated as artworks. In addition to providing accessibility consultation on the exhibition, Neuk Collective also designed Quiet Space (2023), a separate, low-lit room with seating and a range of reading materials related to the topic of neurodiversity intended as a restful, low-sensory environment – particularly for those neurodivergent visitors who can be overwhelmed by loud and busy spaces.(2) Quiet Space also features a wall-based illustration titled Double Empathy Theory (2023) produced by Neuk Collective member Tzipporah Johnston, explaining the barriers in communication between autistic and non-autistic people. Inflatable works by Lobb, an autistic artist with fibromyalgia, occupy Te Tuhi’s foyer as well as the main exhibition space, which is partitioned by two orange-tinted PVC curtains that externalise the ambient interior of the works. Pineapple Place in Yellow Space and the aforementioned Orange Cathedral (both 2021) offer a calm space to anyone requiring a reprieve from the sensory information of the exhibition, while also engaging the senses as a form of embodied intelligence – an idea similarly explored in Stefan Kaegi (Rimini Protokoll) & ShanjuLab's video work Temple du présent: Solo for an Octopus (2021) through the example of the octopus’ distributed mind.

.-Designed-by-Robyn-Benson.-Commissioned-by-Te-Tuhi,-Tamaki-Makaurau-Auckland.-Photo-by-Sam-Hartnett.jpg)

Neuk Collective, Quiet Space (2023), installation view. Designed by Robin Benson. Commissioned by Te Tuhi. Photo: Sam Hartnett.

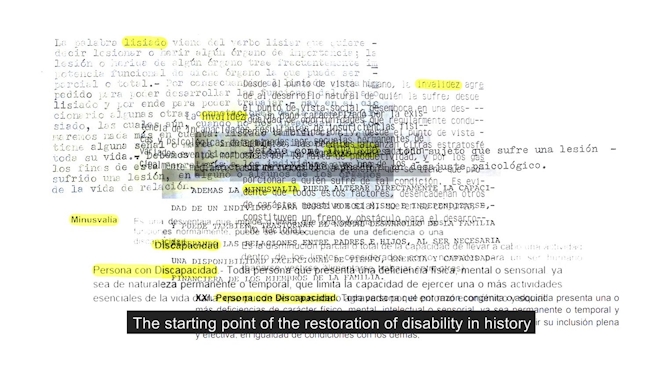

As listed artworks, Quiet Space and Double Empathy Theory also exemplify the didactic function of many of the works in the exhibition, which contributes to its generally explanatory feel. These largely text-based works anchor the exhibition while also offering multiple points of entry to the topic of neurodiversity for visitors who may be less familiar with the term or its associated concepts. The chronicle of <_______>’s project The chronicle of < cognition > (2022–), and Ana García Jàcome’s The [ ] history of disability in Mexico (2020) and It’s like she never existed (2018) are several narrated, essay-style, and documentary videos that alternately take macro and micro views of neurodiversity, delineating social and personal histories of disability by examining the long history of neurodivergent and disabled people’s institutional marginalisation. The chronicle of < cognition > (2022–) also includes a large diagrammatic vinyl wall work that is accompanied by a number of other schematic artworks in the form of García Jàcome’s series of Venn diagrams (2021), Prue Stevenson’s Don’t fear the meltdown (2018), and, perhaps more abstractly, Martin Awa Clarke Langdon’s Tohutō (macrons) (2018–23). Particularly reflecting the gallery context, Simon Yuill’s large text-based wall work The Ableism of Networks (2020–23) theories the marginalisation of neurodiverse people from the networking activities that constitute the source of much of the art world’s social capital.

.-Curated-by-Bruce-E.-Phillips.-Photo-by-Sam-Hartnett.-(1).jpg)

Installation view of Who can think, what can think, Te Tuhi (2023). Curated by Bruce E. Phillips. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Ana García Jàcome, The [ ] history of disability in Mexico (2020). HD video and sound, English with closed captions, 15 min 38 sec

While these more didactic artworks provide the conceptual and historical scaffolding of the exhibition, others that address notions of non-human cognition take more poetic or speculative routes, in a departure from text-based language that is perhaps apt for their non-human subject matter. Works in Who can think, what can think that consider cognition in plant life include Jae Hoon Lee’s Roots (2006), a large wall-based composite photograph that visualises the networked intelligence of trees, and Prue Stevenson’s Bio-Neuroambiguous (series) (2018), a sequence of three head-shaped planters potted with growing ferns that represents neurodiversity among humans as being analogous to biodiversity among plants and animals.

Jae Hoon Lee, Roots (2006), digital print. Image courtesy of the artist.

Two further video works are dedicated to machine thinking, or in other words—and as understood in the global context of big tech—the thinking of capital. Assembled entirely from stock footage and narrated by a voice actor, Laresa Kosloff’s New Futures™ (2021) imagines a future in which genetic engineering technology has developed to enable the replacement of personalities, resulting in an upper class of “synthetic personalities” backed by the trading of stocks based on social popularity. Like Yuill’s The Ableism of Networks, New Futures™ reflects on the exclusion of neurodivergent people from the default extroversion required in spaces where social performance is equivalent to capital gain, while similarly addressing the neoliberal notion of self as brand that underpins this relationship. Also using found footage, Kite and Devin Ronneberg’s Fever Dream (2021) is an interactive video installation that produces new combinations of video and text when triggered by movement in the gallery space, collapsing footage culled from the internet with ominous AI-generated text relating to the fate of humanity. Drawing connections between settler colonialism and big data, Fever Dream also serves as an exercise in machine cognition, tapping into concerns related to artificial intelligence that have gained renewed relevance with the prominence of large language models such as ChatGPT.

Laresa Kosloff, New Futures™ (2021)

These imaginative and speculative artworks divert from language and cognition as understood from an anthropocentric perspective, pointing to modes of processing and assembling information that exceed the mechanisms of human cognition. Primarily, however, Who can think, what can think is marked by a prominence of text-based artworks and supporting documentation. This reliance on the textual results in an emphasis on discursivity that is characteristic of the “educational turn”, a development in contemporary curating that describes the way in which discursive practices have come to constitute the “main event” of contemporary art, rather than existing solely as a “by-product” of other creative processes.(3) It encapsulates much of how we have come to understand contemporary art practice, in its pedagogic approach to open-ended dialogue and speculation, and its resistance to pre-determined outcomes, and is evident in the collaborative and processual tenor of artist development initiatives and public programming of many contemporary art galleries.

Democratically framing the gallery visitor as a co-producer of knowledge rather than a passive recipient of authoritatively determined meaning, this framework became reified within contemporary art and the curatorial zeitgeist when Paul O’Neill and Mick Wilson’s book Curating and the Educational Turn was published in 2010. In the intervening years, conversations regarding the accommodation of a diverse range of needs have risen to the fore of public art gallery’s concerns, introducing notions of “accessibility” and “inclusivity” into common operational parlance. And while public galleries have for some time now been aiming to diversify their audiences through expanding both their communicative and structural means of access, the discursive model theorised under the banner of the educational turn remains the dominant curatorial framework within the development of contemporary art exhibitions. In an article that proposes gallery and museum educators, not curators, be the primary instigators of working relationships with disabled artists, writer and curator Amanda Cachia identifies the failure of the educational turn to address questions of access. She argues that while the educational turn seeks to empower audiences as co-producers of knowledge, the framework offers no affordance to the equitable empowerment of disabled audiences, nor then to such audience’s equal participation in the production of this knowledge.(4)

It is clear from its inclusion of neurodiverse and disabled artists, attention to exhibition design, and multi-modal selection of artworks that considerations of access have strongly informed the curatorial approach to Who can think, what can think as much as they do the content of the featured artworks. The exhibition’s discursive emphasis, both in the artworks themselves and the supporting material, does raise the question of whether it might privilege certain modes of perceptual understanding at the expense of others, due to its reliance on artworks that require reading rather than those that foreground sound or texture.(5) Of more interest, however, are the questions the exhibition’s textual emphasis raises about the communication of contemporary art more generally. Catering to the entire spectrum of information processing differences within a single exhibition is likely to be an impossible task, but it asks important questions about the ways in which art can be communicated to accommodate such differences, and perhaps about the problem of communicating contemporary art at all. How should something as complex and esoteric as contemporary art be communicated to its audiences? In what ways? Is it worth it?

The chronicle of <_______>, Neurodiversity in Aotearoa (2023). Presentation by Bruce E. Phillips as part of the collaborative project The chronicle of < cognition >

The answer, if there is one, seems to lie in the very function of an art gallery itself. As explained in The chronicle of <_______>’s video that considers neurodiversity in Aotearoa, notions of cognition and their attendant definitions of intelligence have played a key role in the historical shaping of social institutions, particularly in the context of categorising sanctioned intelligence and pathologising anything that fell outside of its bounds. Art galleries as cultural institutions are not free from their own founding assumptions regarding cognition and the white, bourgeois subjects they were established to edify. But as spaces of civic engagement, they are now part of a large-scale reassessment of public space, of which accessibility is a driving concern. In the past two years, international exhibitions such as Metro Arts’ Conversations on Shadow Architecture (2021), the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art’s Who’s Afraid of Public Space (2021–22), Serpentine Galleries’ HOLDING SPACE ACROSS CRIP TIME (2021), and MMK Frankfurt’s Crip Time (2021–22) have broached sympathetic concerns regarding civic subjecthood in light of neoliberalism’s erosion of the public sphere, and its foreclosure of states of being that do not operate according to its mandates of optimised efficiency.

The lens of disability tells us a lot about the ways in which the spaces, structures, and systems of contemporary society disable certain physical and cognitive abilities while enabling others.(6) “Access” and “accommodation” are thus issues of a civic nature, and public contemporary art galleries the ideal fields within which to press such emergent (and urgent) ideas into form. Importantly, they are also stages for the generative conflict that is required for such ideas to take shape. The conflict between artwork and text—and what is perhaps the inherent impossibility of closing the gap between an artwork and its interpretation—is a productive tension, and one that is worth struggling over. While the interpretative aids and text-based emphasis of Who can think, what can think may lend the exhibition a certain textual density, they are exemplary of this necessary struggle to communicate new or complex ideas in spaces of contemporary art—one that makes dialogue possible, a crucial part of being public, by which we might mean accommodating publics. Multiple points of entry are essential—and soft spaces, too.

Alena Kavka is a writer and art professional based in Tāmaki Makaurau whose interests span the intersections between contemporary art, writing, and public space.

.-Series-of-three-billboard-prints-and-a-digital-poster.-Photo-by-Sam-Hartnett.jpg)