Kahurangiariki Smith’s art and curatorial practice is strongly focussed on the materiality of digital media and a kaupapa of indigenous futurism grounded in mātauranga Māori. Her art reflects media that she is engaged with daily, such as gifs, karaoke and video games. Her video games FOB (2016) and MāoriGrl (2017) have been exhibited in galleries and museums across Aotearoa. She currently works at St Paul St Gallery, Auckland University of Technology as the Curatorial Assistant. Kahurangiariki believes there is power within the intersection of traditional perspectives and contemporary media. Here, within that tension, one may explore the potential for indigenous voices in unlimited ways.

In this interview we talk about her collaborations with her māmā Aroha Yates-Smith, her process around navigating tikanga in the digital space and the makings of MāoriGrl. I was excited to be able to talk with Kahurangi in the flesh and share food together after the second Tāmaki lockdown.

Israel Randell (IR): Firstly thank you so much for inviting me into your whare today, lets get the ball rolling, ko wai koe? Nō hea koe?

Kahurangiariki Smith (KS):

Ko Kahurangiariki tōku ingoa

Ko Horouta, me Mataatua, me Takitimu, me Tainui ōku waka

I’m from all over the place, I grew up in Kirikiriroa. My mum is from Rotorua and our papakainga is there. My Dad is Pākehā but grew up in Whitianga. I have two brothers, who used to get me in trouble a lot. I moved to Tāmaki 5 years ago to do my undergraduate at Whitecliffe, from there I slowly started exhibiting some mahi and recently I’ve been working at St Paul St Gallery as curatorial assistant. The first work I showed was called MāoriGrl, which is currently at the Waikato Museum. I’m actually going there this weekend to reprogram the controller.

IR: Do you do all the programming for these games?

KS: I wouldn’t call myself a programmer, but yeah, I do it all. I’m still googling how to do things half the time.

IR: Can you tell us about your games?

KS: My first video game was called FOB (2016). At the time I was considering Aotearoa’s history and asking who’s fresh off the boat when we’ve all arrived here on one waka or another? At the same time I was learning about Tupaia and playing with his paintings from his time on the Endeavour and repainting them with tourists. From there FOB became a video game, inspired by the old arcade games. You throw money at the savages and get points. But you can’t win it, because I forgot to programme that, haha, but let’s just say that it’s intentional, haha. But once you lose, it comes up saying “You’re a shit coloniser, you got eaten with a taro milkshake later that night.” So it’s a total piss-take on colonisation.

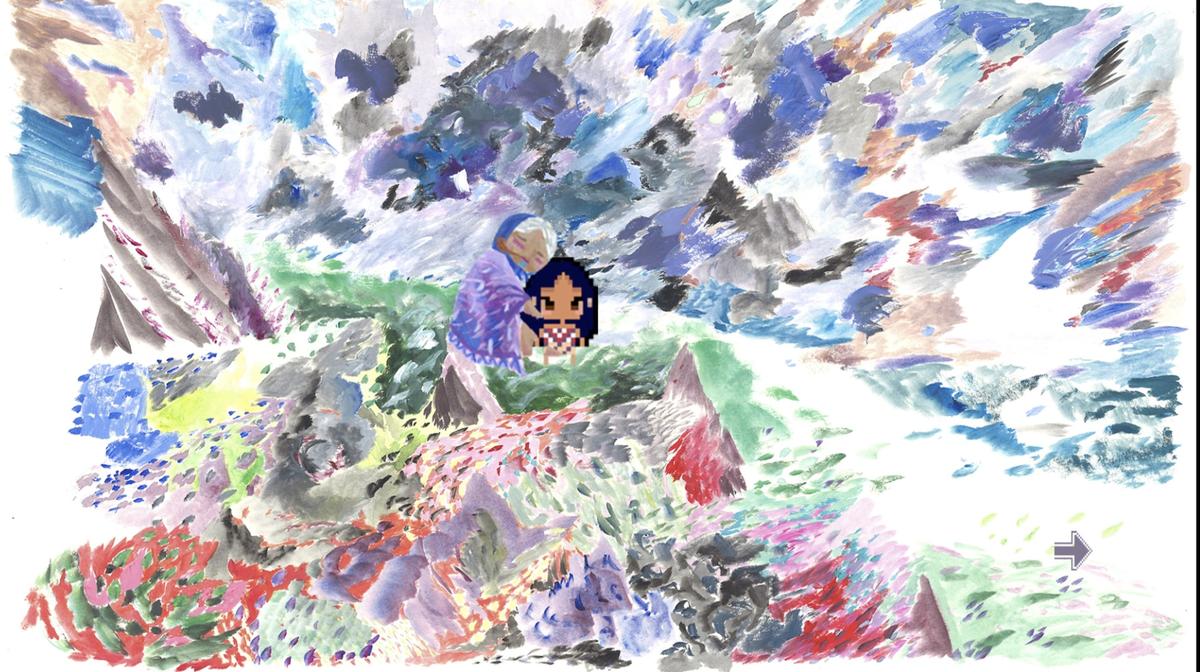

MāoriGrl (2017) was the second game and it was the first time I had collaborated with my mum. She wrote her thesis, Hine! E Hine!: Rediscovering the feminine in Maori spirituality, back in the ’90s about ngā Atua Wāhine and MāoriGrl drew particular narratives from her thesis around Hinetītama and Hinenuitepō. In a lot of the ways Hinenuitepō has been portrayed in recent decades like she’s evil. She killed Maui, but it doesn’t tell her story or share her point of view at all. It made me think if they can look down on someone of her status, someone who can give and take life, how would they look at Māori women, you know? I just thought what if I could share her narrative in a more positive light? That then became the starting point for a lot of my mahi. MāoriGrl was quite a beautiful process. I’d call my Mum all the time late at night at Uni asking for help, or checking in to see if certain things were ok. For me, it brought my understanding of atua wāhine to new light.

MāoriGrl (video game demo) (2017) Kahurangiariki Smith

You throw money at the savages and get points... But once you lose, it comes up saying “You’re a shit coloniser, you got eaten with a taro milkshake later that night.”

IR: Where did the drive to make video games come from?

KS: I learnt how to read from video games when I was a kid. I grew up playing JPRGs(1) and watching anime and Studio Ghibli films, so it’s very nostalgic. For me, video games seemed like the perfect format to use for storytelling because there’s a level of empathy demanded when you’re put in someone else’s shoes that makes people really engage with the kaupapa. You can’t just walk past it. People are always like, “what’s that?” They want to tutu, and that’s one of the things I love about it. The tutuness of it, it’s very tangible. It’s almost a play on storytelling in our own oral traditions.

IR: I’ve been really interested in how artists experiment with narratives, pūrakau or whanau/hapu/iwi stories and their processes around negotiating that space. Some people like to ask for permission, some don’t and there’s a lot of grey space around who is allowed or not allowed to do things. What was your thought process around telling these old stories through this new media?

KS: I was really safe in that I had someone in my immediate whanau who I could talk to about that. Your worst fear is that you’re going to do something wrong, especially when it’s almost like an act of love to make art for your own people and retell these stories. But for me, the whole thing around seeking permission serves as a way to make sure your process is caring for the people you're drawing from. Because you have to maintain those relationships and make sure that you’re giving those people the respect they deserve. And in turn, I think your work will hold up. But also your work has an integrity to it when you go through all of these steps. It’s scary at first, but you do become more comfortable with it, you draw upon your community to ask questions. This isn’t stuff you can necessarily Google either. You have to go out into your community and find out things. So it's quite a beautiful way to draw upon the knowledge the different people have, and your whanau around you. I’ve still got a long way to go with connecting more with my hapū and iwi.

IR: Do you think you would have embarked on this project if you hadn’t had your Mum?

KS: I don't know that I could have done it if I hadn’t had Mum. Growing up in Kirikiriroa, our whenua is in Rotorua and Turanganui-a-Kiwa. I haven’t been raised in my papakāinga, so it would have taken a long time to reconnect and begin this mahi. I still think I need to go back and spend some time with those places though. But because Mum was a phone call away, knowledge about atua wāhine was super accessible. But not everyone has that type of access to these old stories or reo, which is one of the many tragedies of colonisation. Making video games about our old stories, especially if the mahi is also a bit cheeky, I always wonder “Am I gonna get in trouble for this?”, haha. But all of our tīpuna have already done a lot of mahi to get us here today. Now we have the freedom to continue adapting and just being a tutu because we can. I think that's a blessing really.

But for me, the whole thing around seeking permission serves as a way to make sure your process is caring for the people you're drawing from. Because you have to maintain those relationships and make sure that you’re giving those people the respect they deserve. And in turn, I think your work will hold up. Your work has an integrity to it when you go through all of these steps.

IR: How was MāoriGrl received by its many audiences?

KS: There were different reactions. Some kids said it was boring, one person cried, and some people (old people) just straight up don’t know how to engage with video games. Also I hadn’t thought of physical access, my first installation was on a mat on the floor in a whare I had built, and not many people could sit down on the ground, which I hadn’t even thought about. I reckon kids are the best audience because they’re so honest.

It’s been received well but I still see it as a starting point (as) opposed to a finished mahi. I need to keep retelling stories like this with Mum and with her writing. For some people I spoke to, this was their first time hearing about Hinetītama and Hinenuitepō. So I imagine it more as an educational resource in a way, for people who haven't had access to these stories before, or for our tamariki that just wanna tutu and play video games and it happens to be stories of our tīpuna.

IR: Do you think the gallery space serves the work's format?

KS: I would like to take it out of the gallery space and maybe into teaching and using it as a resource. People often ask if I wanna make MāoriGrl into a mobile app and sell them, but I’d rather not because with heavy subjects like Hinenuitepō, you want to make sure that it's a safe environment, like you aren’t eating kai and playing the game. How do you maintain a level of tikanga in a digital space? How do you maintain tikanga in a gallery space? That's something I’m trying to be cautious of. One way I found helped was to keep the video game presented on a mat or a whare-like structure, and no kai, drinks or shoes were allowed within that space.

IR: And when you're making something quite deep you have to be mindful of the galleries and institutions who it will come in contact with, and the curators who will care for it, and the life it takes on after you’ve made it.

KS: Yeah, when you're making mahi and you're trying to get it ready for the deadline, you forget that it has another life in the gallery. But ultimately these are all of our stories, so I try and take care of them and make them accessible.

IR: How do you navigate sharing this resource whilst also maintaining the intellectual property?

KS: I want to share it as much as possible but so far, other than exhibiting them, I’ve just kept all the game files to myself. I haven’t figured out a way to distribute these video games in a way that feels tika. I keep them on a hard drive but that doesn’t feel like the right space either, like, having them on a hard drive to yourself? I don’t know, I feel like there's an inbetween where you can still share and have them safe, but (also) have the file there for when people want access. It's a tricky one. So far, having MāoriGrl exhibited in the Waikato Museum feels like the right balance of access and tikanga, where it’s surrounded by taonga. Access is something we're trying to navigate with Mum's thesis too. We're wanting to get it published. Even though it came out like 20 years ago, it’s never been published properly. So we're wondering, "Do we put it online? Do we make it like a book that people have to buy? Can everyone afford a $30 book? Can we do both?" Also I’m having to introduce my parents to like, a pdf, haha, so it's an interesting space to be in.

IR: What influenced the visuals in MaoriGrl?

KS: Just gaming really, old school arcades. MāoriGrl is a mix between hand painted and digital. The backgrounds are just imagined landscapes of what our whare used to look like, or what our landscapes could have looked like. But the rest of it is like the old 8-bit video games, I love how they look.

IR: Can you tell us a bit of the story of Hinetītama you are exploring in MāoriGrl?

KS: The OG one or...?

IR: The one you reference.

KS: The simplified version is probably all I’m equipped to answer. Hinetītama was the daughter of Hineahuone and Tāne, except she didn’t know who her father was growing up. She married Tāne when she got older, and when she started asking the pou in their whare who her father was, they informed her it was her husband. That’s one version, but essentially Tāne was her husband and also her dad.

Hinetītama was deeply shamed, but since she and Tāne already had children together, Hinetītama told him, "Tāne, e hoki ki ta taua whanau, ka motuhia e au te aho o te ao ki a koe, ko te aho o te po ki au." Pretty much she said to him that he will take care of their children in the living world, but in death they will go to her. That was when she transitioned to Hinenuitepō, in my eyes.

I’ve only ever known Hinenuitepō as a caring Atua who’s very giving, not evil at all. But in the game I didn’t know how to tackle themes of like incest. How do you talk about that in a 3 min game, you know? I wasn’t really equipped to get near that, so I only focused on the part where Hinetītama shifts into becoming Hinenuitepō. In MāoriGrl, she meets a kuia in a whare and she tells Hinetītama that they have to go up to this maunga. So they climb this maunga together and that's the first person I imagine Hinenuitepō taking to the underworld. She then climbs out of the cave and sees this kauae, that tells her that she's Hinenuitepō, and that although she can’t see her whanau anymore, she will look after the whanau who comes to her.

IR: I’ve heard so many versions of that story too.

KS: Yeah the original is pretty heavy, I ended up telling this version because it didn’t feel as heavy as telling the whole story. But part of the mahi now is to make mum’s thesis available so that if people wanted to find the full story they could read mum's thesis.

IR: Can you tell us about the work you made with your mum called Mama don’t cry (2019)?

KS: I had just started working at St Paul St Gallery and Natalie Robertson asked if I had any information on Parawhenuamea from Mum’s thesis. Long story short, Mum and I were asked to collaborate with Natalie, Alex Monteith and Graeme Atkins on their installation in Te Tuhi’s [exhibition] Moana Don’t Cry. It was quite amazing to work with way more developed artists. It’s a whole other ball game, they know exactly what they are doing, whereas I’m still like googling stuff and making mistakes. Just that level of technicality I have never worked with before.

IR: And the work?

KS: The work is made up of several of Mum’s composed waiata that I turned into karaoke videos. She’s composed all these waiata over the years, particularly about water. I felt like I needed to learn them. I like karaoke and it’s the only time I sing in any type of public forum, whereas Mum loves to sing. At the time I felt like karaoke would be a good play on rote learning and using karaoke as a way to learn. I learnt te reo mostly by ear, so listening has been a big thing for me to pick up on words.

In the post edit I tried to make it really karaoke-esque with real saturated colours, also I was trying to edit it to give myself a tan, haha. In the work Mum sings her songs and talks about Parawhenuamea and Pelehonuamea [from Hawaiʻi] who linguistically are really similar. So "para" for us is silt, "whenua" is land and "mea" is a really old word for red and Pelehonuamea is similar, she creates lava so there was a really beautiful correspondence between the two atua.

While we were filming she was talking about the two atua and was thinking about her time in Hawaiʻi. She kept crying because at the time there was a lot going on at Mauna Kea. The earrings she’s wearing in the video were gifted to her by Pualani Case, one of the Kuia leading the protection of Mauna Kea in Hawaiʻi. So Mum was really emotional and the title of the work [He tangi aroha—Mama don’t cry] was a play on that and the exhibition title, Moana Don’t Cry.

That work was a really big learning curve for me. Working with Mum, it’s not fair to force someone to work long hours. She’s old and has done enough in her life. It doesn’t make sense to push her when she just thinks it's an opportunity to hang out, you know?

He Tangi Aroha – Mama Don’t Cry (edit) Kahurangiariki Smith

IR: Ohhh bless! That's so cute hahaha! Like "ok mum, we can only hang out if you can help me make good art," hahaha.

KS: It sounds so sad, but it didn’t make sense to make more work with her if it meant that I wasn’t spending time with her anymore. But it was a really amazing time to be together, soaking in all the knowledge. You pick up more than you realise, which made me feel quite familiar with this korero. We ended up going to Rotorua to our awa, which has these tiny springs and we recorded some close up shots of them and paired them with mum singing about Parawhenuamea. It was quite a beautiful way to return home and a nice reason to go back to Rotorua and film there. But also I started to think more about when I have all of this on footage. How do I decide what knowledge gets shared and what is cut, especially in the edit?

IR: I started to think more too about how we protect our whanau who are in footage, and the knowledge. Maybe through film techniques or in small ways.

KS: For me it always comes back to your process, and making sure you're taking care of those you work with.

IR: For those readers who don’t know, who is your Mum? And what’s her thesis? Did she have an art practice or what sector was she in?

KS: My Mum is Aroha Yates-Smith, she studied at Waikato University and she was a Professor there teaching te reo Māori, and within that time she wrote her PhD thesis, Hine! e Hine!: rediscovering the feminine in Māori spirituality. After that she became the Dean of Faculty of Māori and Indigenous Studies at Waikato University. So while Mum didn’t have an art practice she’s always been weaving or in wānanga or giving talks to wāhine about ngā atua wāhine, or old school child birth practices, or teaching them karanga. So she's been involved in many other ways that have informed my mahi.

IR: Has she taught you all of those things too?

KS: She hasn’t taught me how to karanga, but that's not her fault. I'm always like "ahhh na, I’m too shy." But it's cool because a lot of the Atua she wrote about I grew up hearing as bedtime stories and stuff. She’s always been really present with the whenua or moana. Sometimes we’d be driving and she does a little karakia to that awa or maunga to acknowledge it. So she’s shown me that we can acknowledge these atua in a daily way too. These are all things she’s been taught by her koumātua back in the day.

IR: How did you find it working with your mum?

KS: It was cute! She would come stay with me in Tāmaki and she’d help me like paint walls and if I didn’t need any help she would help my classmates too, proofreading or just giving people hugs. Yeah it was really cute! She’s always a phone call away.

I’ve never actually read her whole thesis, I just read the part that was relevant to my work, which kind of feels like cheating, haha, such a bad child. Working with her has been amazing but there’s a new urgency now she has Alzheimer's. She needs naps like all the time. It's different working with your parents. They need rest and coffee and it's a slower pace. You can push yourself, but it's unfair when you're working with others to push them like that.

IR: What did your mum think of Mama don’t cry?

KS: She liked it, but she's really big on grammar. So she would watch it and be like "hey, you missed a macron" and I’d be like "Ugh, man, we went through this like 10 times", haha. She always noticed the mistakes, which is the last thing you want when it's up and installed, but it's real cute! She would sing along to it all the time and it was quite symbolic for her.

IR: What's the best advice your Mum has ever given you?

KS: After she got her kauae, I jokingly asked her, "when can I get mine?" And she was like, "whenever you want or whenever you're ready." It was such a simple answer for such a massive question, you know? Something that has so much pressure put on it, or rather something that is so heavy with meaning and is so significant in a really beautiful way. But to have such a simple answer is really her approach to a lot of things. It wasn’t necessarily advice, it was just a freeing attitude to have towards something so massive.

IR: I think what's come out of these interviews are a recontextualisation of our attitudes towards disruption and replacing it with innovation, as a way to align our attitudes more with our tipuna.

KS: I see it less of a disruption and more of us being back in this space of innovation, and we’re only able to be in this space because the generations before us have fought so hard for us to still be here with our knowledge and our reo. So I see it as a privilege being able to tutu, Tutu is my methodology.