Is the rustling of Snickers wrappers beneath my feet a filmic moment? The gallery floor is strewn with them, and with grapefruit seeds, which I initially mistook for peanuts. Is the weight of a person crushing grapefruit seeds a filmic moment? In the back of my mind I hear Hocken curator Andrea Bell wondering if Campbell Patterson’s artist book is a script for a film yet to be made. If the book were to become a film nothing much would happen, but the simple actions would accrue an intense weightiness. There would also be a lot of repetition. Amongst other mundane activities the protagonist would begin watching a DVD then pause it to pour five cups of tea, resume watching, walk to the beach, and try not to breakdown. Read it if you get the chance.

There are two video works in toot floor and neither bears any narrative resemblance to Patterson’s artist book. Though very different the two videos nevertheless share thematic and formal resonances with the rest of Patterson’s work here at the Hocken Gallery; the aforementioned artist book, the accumulative carpet paintings, the iterative pencil drawings, unique photocopy works and the black and white linocut prints. Yes, there is a lot going on in this exhibition.

toot floor is the outcome of Patterson’s twelve-month residency in Ōtepoti/Dunedin as the 2017 Frances Hodgkins Fellow, and the artist has maximised the opportunity to acquire and hone new skills in a range of media. Patterson’s fluency in multiple media is paradoxically exceptional yet unsurprising; his practice is not only the result of artistic capability, but situated in relation to the near-obsessive strain that characterises his work. However, to someone writing about this exhibition and considering Patterson’s fluency across disciplines, toot floor makes me think about our expectations; both as viewers and art writers.

In the field of conceptually-led practice it is assumed that the viewer/writer will look for patterns of connections and complementarity. Yet in toot floor, something about Patterson’s ability to resolve works in such a broad range of media makes me question these assumptions.

Walking through the gallery, I found myself thinking about the ways in which the Snickers wrappers and grapefruit seeds scattered throughout the three spaces function as a means of cohering the space. Also the loud whirring of air-conditioner units, which could be conceived of as operating in a similar, if aural way. I could also focus on Patterson’s tendency to utilise the situations, locations, and detritus of his surroundings and that which he brings into his world. It is this latter action that can sometimes be overlooked or minimised in discussions of Patterson’s practice. And yes, he works with everyday materials and situations and makes them strange through iterative interventions such as exiting a window wearing only a towel, walking back into the house and repeating (escape 1, 2, and 3, (2017)). But, in the case of toot floor for example, Patterson also actively bought (and consumed) bulk quantities of Snickers bars, grapefruit, and vegetables. Thus, Patterson’s practice encompasses dimensions both purposive and actively contrived.

"toot floor", as the reader may discern, shares an informal semantic similarity with “toilet floor", and from this elaboration other manifestations of bathrooms and floors more generally become readily apparent. The eponymous toot floor (2017-2018) comprises six vertically positioned carpet mat paintings adjacent to one another in two rows of three. The seventh carpet painting is placed horizontally beneath this arrangement next to a smaller silver tray that has singe marks, grapefruit seeds and a small photograph perhaps cut out from a magazine. Whether circumstantial or not, Patterson reportedly noticed a glob of glue on a mat in the studio when he first arrived that set certain trajectories of this exhibition in train. Could this have prompted Patterson to consider mats as a painting substrate? In any regard, here we have a suite of seven paintings that utilise carpet mats as their support, and following the date range of these paintings (2017-2018), we can read time, the accumulation of time, the accumulation of certain processes and actions in time, and Patterson’s attentiveness to time and methodological responses as key constitutive elements in these paintings and other works in this exhibition.

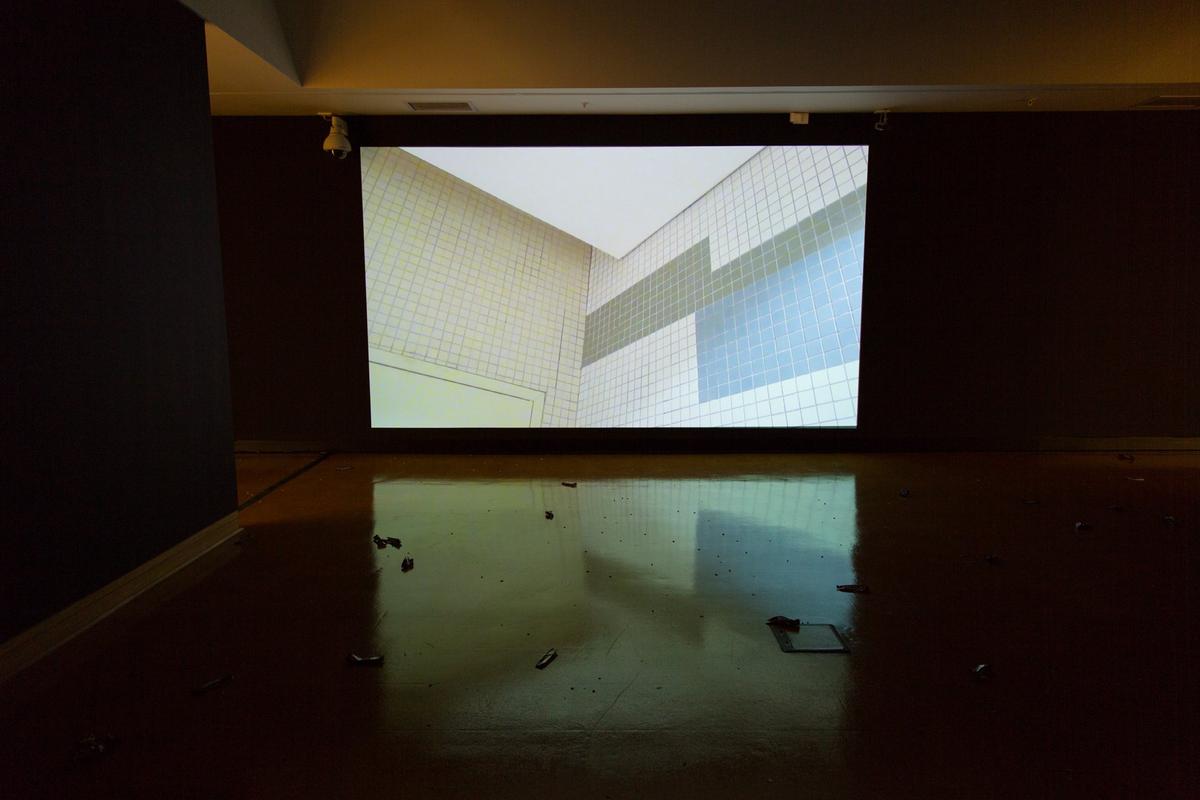

Installation view of toot floor (2018) Campbell Patterson. Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago. Photo: Iain Frengley

Over the period 2017-2018 Patterson added oil, gesso, cardboard, stones, pva, beetroot, red grapefruit seeds, and toilet paper to the carpet paintings thereby invoking the term accumulative paintings. These items have made their way into the paintings as by-products of Patterson’s daily routine, and in this sense can be suggested as accumulating from his year as the Frances Hodgkins fellow based primarily in Dunedin. Two of the paintings whose surfaces are traversed with meandering lines are reminiscent of Patterson’s Last Painting series from 2015 (oil on canvas). Exhibited at our feet on the cork tiles of the gallery, the floor-based form of the accumulative carpet mat paintings is carried over to Patterson’s main video work singapore a/c studies (2017) which includes a rapid-edit sequence of over sixty public bathroom interiors in Singapore. In this work Patterson focuses on tiled surfaces particularly as they intersect with another dimensional axis (floor/wall, for example). Patterson approaches these generally white, anaesthetised surfaces on an angle, isolating convergences and excluding orientating points of reference. This results in a disembodied sequence of cropped shapes that retain a relation to public bathrooms but primarily as a means for exploring and exploiting formalist concerns. It is noteworthy that Patterson himself, who is so frequently the subject of his video work, does not appear. In the artist talk Patterson described singapore a/c studies as his least embarrassing, least humiliating video work.

The 'a/c studies' in the work’s title names the aural immersion of toot floor. This is the loud drone of air-conditioning units that boom beyond the gallery space and down the stairs. It is the first element of the exhibition to reach the visitor. Patterson edited out all other sound from the sixty plus public bathrooms he recorded in Singapore. From the “a/c” (air-conditioning) in the work’s title, and the enveloping presence of the aural dimension, it is possible to interpret sound as more significant than the video itself. Sound and video register as separate entities, as the sound - which builds slowly in waves - is not consonant with the fast-pace, abstract bathroom shapes. Inside the central gallery space, the video is sited opposite the entrance doors while the sound emanates from either side. It is a configuration that quite literally separates sound and moving image. Whether the emphasis on sound suggested here indicates a new direction for Patterson remains to be heard.

It is fairly well known that during Patterson’s Hodgkins residency he worked mainly at night listening to a genre of music called Depressive Suicidal Black Metal (“DSBM”). I mention this not only because the walls of the central gallery were painted black, or because Snickers may be a good way to power through the night, but because formal qualities of DSBM are said to have leaked into the exhibition. The music or its influence can perhaps be discerned in three of the work’s titles; old style pathetic (2018), apathetic drums I (2017), and apathetic drums II (2018).

old style pathetic is the title of the second video work and features small pools of light emanating from tea-light candles that barely move amongst a wash of purples and blues. Patterson filmed this light and colour field from night to dawn although there is no dramatic revelation of morning. old style pathetic gains much of its aesthetic from Patterson’s use of outmoded video technology to shoot the work, which lends the image a quality of gentle weariness.

I began this study of Patterson’s exhibition by asking whether the impact of footfall on Snickers wrappers and grapefruit seeds could be considered filmic moments. The impetus behind this line of questioning is partly to do with acknowledging the "frame" of CIRCUIT as a platform for some of the artist’s film and video works. Yet the question of the extent to which non-filmic works could be conceived as filmic seems particularly pronounced in series of prints (2017) and the aforementioned pencil works apathetic drums I and II.

Installation view of toot floor (2018) Campbell Patterson. Featuring apathetic drums II (2018) and apathetic drums I (2018), pencil on paper, courtesy Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago. Photo: Iain Frengley

The two bodies of work are hung in opposite ends of the gallery on white walls. It is perhaps only a passing observation to draw attention to these framed works as filmic stills, and perhaps equally tenuous to attribute any deep association of film with time or time with film, for surely time is in and of everything. Yet the association between the prints and filmic stills lingers. And time. Likewise, much has been made of the labour in both of these series, yet why should the idea of art labour seem strange or unexpected? Patterson has undoubtedly laboured to assemble toot floor and one of the subjects of this work has been not just time itself, but what it means to work creatively in an allotted amount of time free from the customary pressures of additional work commitments.

In apathetic drums I and II the drum in these titles could refer to the drums of DSBM, the regular droning of air-conditioning units, a circular motif or an oil drum. In the case of apathetic drums I, each drum, each circle represents 100 days labour. This work is then reversed as a mirror image along the central vertical axis (the work is a framed diptych).

apathetic drums II is a series of prints comprised of seven separately framed works installed floor to ceiling in a vertical line. In each of the seven prints a vertical and horizontal axis forms an idiosyncratic grid that contains in each square a circle of negative space (the area around the circle is coloured in). Each “negative circle” represents every minute of every day of one week. This work resembles most closely a strip of film negatives or a sequence of filmic frames. Here Patterson’s work finds kinship with On Kawara’s series Today (1966-c2014) in which Kawara painted each day’s date, and Tehching Hsieh’s many time-based performances such as One Year Performance 1980-81 (Time Clock Piece) during which Hsieh punched a time clock every hour for a year, taking a photograph of himself each time (subsequently becoming a six-minute film). Patterson’s practice can certainly be aligned with the compulsive methodologies of Kawara and Hsieh but the constraints he sets are his own, however filmic, however consonant or dissonant. In toot floor Patterson successfully corrals the grimy with the meticulous and the abject with the rescued.