Robert Leonard (RL): You made New World to a brief: to make a short film in response to Julian Dashper’s writings...(1)

Gavin Hipkins (GH): This is the second time CIRCUIT has commissioned a group of filmmakers to respond to an artist’s writings. Last year, it was to Joanna Margaret Paul’s poems, now it’s to Julian’s writings. When I heard about the project, I wanted to be part of it. I thought I’d be a good match. I met the curator George Clark in Auckland in November last year. We visited my Starkwhite exhibition of Block Paintings, which recall Julian’s generic-abstract works.

The commissioned artists had four months to come up with something. I worked through a couple of ideas early on, but rejected them. I thought of filming Julian’s studio in Waterview, Auckland, as a stalker movie, like the surveillance scenes in David Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997) or Michael Haneke’s Hidden (2005). I also thought about referring to Julian’s 1994 work Future Call, where a phone is ringing but no one is answering. But this idea—or any reference to a fax machine—seemed obvious. I assumed one of the other commissioned artists would refer to Future Call—and Daniel Malone did.

Julian’s writings include lots of lists. He was focused on the fragment. Some of his writing is about his travels in America. He loved American modernism, cowboy boots, and country music. He wrote on his visits to New York and Chicago, but also to Texas—to Marfa (where he had a residency) and Houston (visiting the Rothko Chapel). So I thought I’d make a work about Texas—a place I’ve never been—and to structure it as a sequence of fragments.

RL: For Dashper, the USA was the centre and New Zealand the periphery, but he could also identify them.

GH: Julian used to have a mantra—‘here is here and there is there’—referring to the distance between New York and Auckland, but he also alluded to a shared can-do attitude that evolved out of the pioneering spirit. This attitude turned its back on the Old World and its stuffy class values, promising a more egalitarian nation state.

RL: The USA and New Zealand are colonial settler cultures—new worlds. Both relate to what you’ve called a "frontier thesis."

GH: I’ve long been interested in the ways that nations mythologise their identities and shape their histories. I explored this in Folklore: The New Zealanders, the exhibition I curated at Artspace, Auckland, in 1998. Later, while studying in Vancouver, I travelled through the Pacific Northwest taking wilderness-themed photos for The Next Cabin (2000–2). That project was informed by a new frontier thesis—the Republic of Cascadia independence movement.

RL: Do we need to read New World in relation to Dashper? What difference does the commission context provide?

GH: New World is a product of a specific commission, but it is also in conversation with my other works and recurring motifs. The references to Julian are oblique. In the context of George’s curated programme, the film will be read in relation to Julian, but this reading doesn’t need to be exclusive.

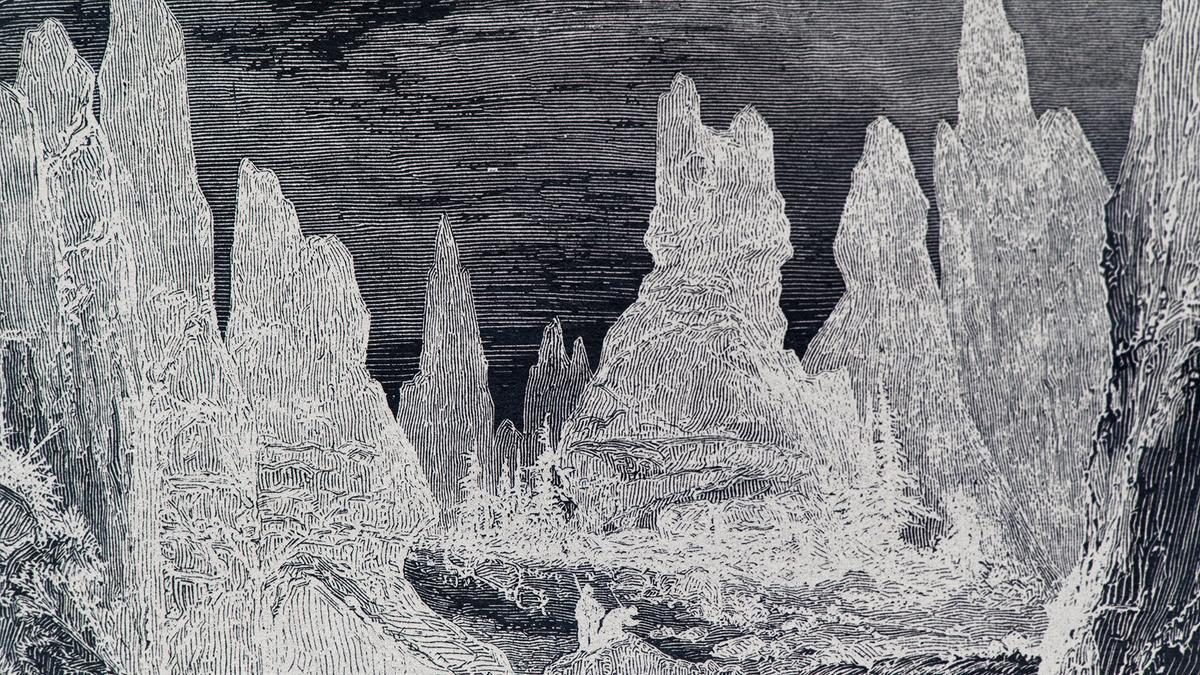

Still from New World (2016) Gavin Hipkins

RL: New World is a deconstructed western, a collage western, a meta-western. What drew you to the genre? What westerns did you look at to prepare? Why make a western—this western—now?

GH: I saw Jim Jarmusch’s masterpiece Dead Man (1995) at the cinema when it came out and felt a profound sense of dread, of loss and mourning. It took me years to return to it and to fully appreciate its more absurdist moments. At this year’s Film Festival, I saw the restored version of Marlon Brando’s One-Eyed Jacks (1961). I sat near the front to soak up its filmic lushness. I lent back and listened closely to the soundtrack. While developing New World, I made lists of westerns, like Julian’s inventories. While working on it, I listened to America’s song A Horse with No Name (1971) over and over. It starts with a banal description of the landscape—"plants and birds and rocks and things"—then takes the listener on a metaphysical journey to a dead river bed. Now is an important time to look at American mythology, which is so amplified by the media in this year’s presidential campaigns. The most powerful nation on earth … the global consequences … and all that.

RL: Your film’s narrative backbone is provided by lines of text on coloured backgrounds—intertitles. I assume they are quotes. Where do they come from?

GH: They’re taken from a report by Edward Smith encouraging immigration to North-East Texas. It was published in London in 1849.(2) I love the descriptive nature of the writing. It’s poetic without trying to be. It offers practical advice (what tools to take, the best time of year to travel, etc.) and speculates on what will become of this place, its politics and peoples. I took excerpts but retained the original sequence. There’s mention of animals, women, and slaves—in that order. The report has a prophetic quality. In hindsight, we know the civil war and the abolition of slavery are on the horizon.

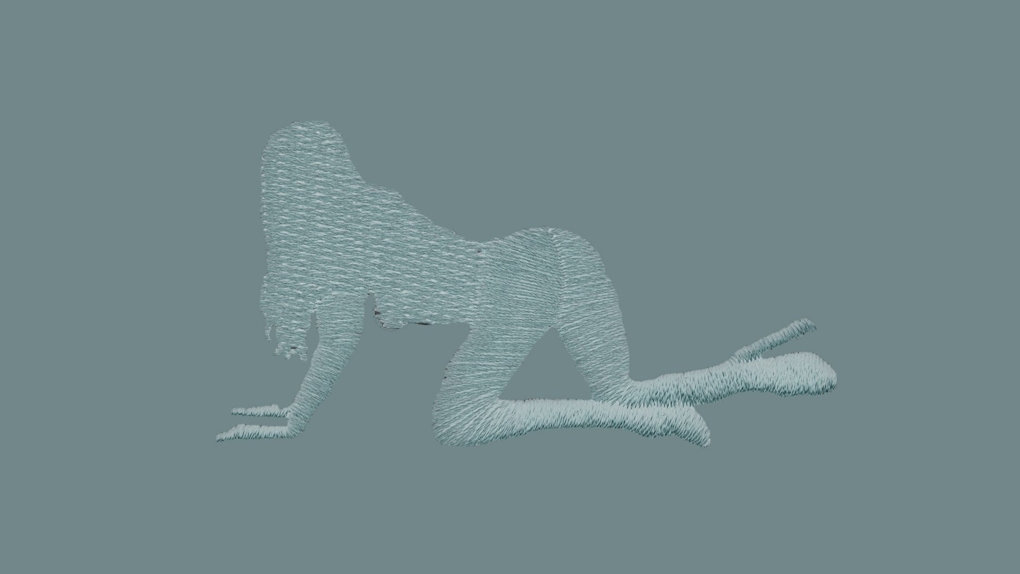

RL: Your film has a deconstructed, bare-bones structure. It consists of repeated contrasting elements that remain more or less distinct. There are intertitles. There are simple flag-like abstractions, recalling Josef Albers, Don Judd, and Dashper. There are treated graphic and photographic images, some of which have a rather oblique relation to the western theme. (These include images that have been rendered as embroidered patches, then scanned and digitally treated.) Plus, there are soundtrack elements. Your film scrambles different time frames—texts from the distant past and photos from the recent past resonate with one another.

GH: The text is from 1849. The plates are from a book, American Pictures Drawn with Pen and Pencil, from 1876. The photos are solarised snippets from issues of National Geographic and Penthouse from the early 1980s (print culture). And there’s aerial footage of Texas from Google Earth from now (Internet culture).

The magazine images—which include shots of cowboy boots and a whisky advertisement—speak to the mythologised landscape and pioneering times, evoking a nostalgia for breaking in the land and its peoples. National Geographic articles take a focused look at communities and their ways of life in a wholesome journalistic manner. The farmer represented at the start of the film stands in for all farmers. The Penthouse model with her eyes closed can represent the love interest—a staple subplot of the western genre.

I’m interested in the transfer of meaning across time, in how the past shapes today’s ideologies: theories of race, the desires of the leisure class, the juggernaut of consumer society. And all this set against a mythologised and gendered landscape backdrop that’s there to be tamed.

Still from New World (2016) Gavin Hipkins

RL: Many of the photographic images have been digitally manipulated to recall treatments from the time of wet photography: overexposure, fogging, solarisation.

GH: The film scrambles elements of pre-digital and digital photography. It nods to the rephotography of Richard Prince, which originated in the late 1970s, in the threshold moment before print culture died out, before digital imaging and the Internet. (Of course, Prince also addressed the western, via print, via the Marlboro Man.) My own conversation with this moment involves going back to mash up some modernist, avantgarde photography with the legacies of a post-war print culture.

RL: In the film, the photos are presented as static images, except for several aerial views, where you track across the image as if tracking across an actual landscape. These God’s-eye views separate the film into chapters or movements.

GH: Today, Google Earth is a powerful tool for accessing places we have never been. It was a way for me to look around Texas without going there. The aerial footage follows Smith’s 1849 journey, from Red River into the Texas heartland. Google Earth offers a sense of movement in real time, so that it’s easy to forget you’re looking at a still photograph. In the film, the aerial passages function as structural markers that pop us back into the historical present—this era of surveillance. The aerial visual mapping complements the nineteenth-century textual mapping in the intertitles.

RL: Religious images and references keep cropping up in your work. What is the role of the religious in your work generally and in New World specifically?

GH: There’s certainly an undercurrent of Christianity in my work. My mother is Catholic and my father an atheist, so I grew up in this place of ongoing ideological conflict—not always dramatic conflict though, frequently comical. Dealing with that tension has been important for my work. When I was 22, I spent six formative months travelling in South-East Asia and India, and I’ve returned to India twice for extended periods since then. After I completed my BFA at Elam, I spent a year studying India’s religions and literary traditions, so, in my work, there’s a touch of hippiedom and its flirtation with Eastern philosophies. In New World, religion in an age of colonial expansion is portrayed as brutal and hypocritical. There’s a passage that sums it up: "Wives are scarce. Girls are being married before they reach their fifteenth year. The Sabbath is much respected."

RL: Like the Victorian-period male accounts you use in other films, this text seems to stand in for your own enquiry as an artist. What’s at stake in this?

GH: The texts I use (some factual, some fictional) are often travelogues and often involve encountering the Other. In my film Erewhon (2014), Samuel Butler’s protagonist discovers a generic people, a hybrid form of the Other, and describes them as things—exquisite objects. To stand in for them, I used images of exotic flowers. You ask: what’s at stake? I think what’s at risk is perpetuating Victorian theories of race and class today. I connect with that colonial history through my own English, Irish, and Scottish ancestry. In 1884, the Hipkins side emigrated to New Zealand from Birmingham. The movements of my extended family from Great Britain is fairly easy to trace. Since making New World, I’ve discovered that the Hipkins family who emigrated to Virginia were slaveholders. The nineteenth century feels very close to us today. As Walter Benjamin proved, it’s the foundation of our modernity.

RL: Sometimes you seem to identify with power, even to romanticise authority.

GH: My use of both pictorialist and arch-modernist aesthetics continues to run the risk of being romantic and fetishistic. Yet, for me, calling on these styles encourages a deeper understanding of languages of style and power, and my work inverts their legacies through both miniaturising and monumentalising. For example, with The Trench (1998), Le Corbusier’s colossal, posthumously realised Open Hand sculpture is turned ephemeral through this small, clunky slide projection; whereas, with the recent Block Paintings (2015), children’s humble wooden toy blocks are stacked, photographed, and enlarged to become imposing militant designs or hard-edged abstract paintings.

RL: Years ago, I described you as a cryptofascist.

GH: They were wrong to kick Lars von Trier out of Cannes in 2011. When he said he was a Nazi, he meant we’re all Nazis. He was acknowledging the fascist and racist in himself as a starting point for self criticism, not celebrating it.

RL: Early on, you made artist-type videos for galleries, but, around 2010, you started to make proper films, films that could be shown in cinemas. You transitioned into this new mode of production and distribution. You shot a few films in a conventional way, using actors (The Master 2010, This Fine Island 2012, and The Dam (O) 2013), but your more recent films seem to have rejected this approach, being more based in the language and aesthetic of your still photography. New World is epic, but I imagine it was made on a tiny budget. How do the economics of filmmaking relate to its visual economy?

GH: When I started making films in 2010, I was disillusioned with the limits of art-world pathways—curator and dealer hierarchies. I was interested in other means of distribution. Respected festivals make open calls for filmmakers to submit their work. Of course, there are still hierarchies, but the increased potential of reaching audiences excited me, especially internationally. My first three films relied on more-or-less conventional scripting, shooting, and editing. In the process, I learnt a lot from professionals and I was grateful for their input. But, I soon recognised that my work could become generic. The idiosyncrasies generated when small and large decisions are made by me as an individual artist get flattened out in a broader, collaborative environment. So, I took more control at all stages, including shooting and editing. It feels like a good balance at the moment. I still work with a small team, including Ben Sinclair, who did beautiful job on the sound for New World. As you note, the move to smaller productions is also determined by resourcing. I am looking for a more sustainable and fluid model of production, so I can keep getting my ideas out there. My film work and my photographic work are now more closely aligned. There’s an evolving space between moving and still, shifting and static.