Four kids are one too many. Not for any Malthusian reason, just the constraints of the average automobile. A fourth child demands a different kind of vehicle, asking the expanding family to leave the safety of the compact sedan for bulkier rides. For my family this meant the purchase of a second-hand, pale plum Mitsubishi Chariot—an almost minivan catered to the family that’s blown past five-seat status but not yet reached the Catholic proportions of a genuine van. Rather than a third bench in the rear, the Chariot boasted two individual seats that could fold up and down in the boot space. It’s a car for taking a lot of people on the road, packed in tight, going places. On long drives we’d save precious room by only using one of the folding seats. I was the fourth kid, and it was my station to occupy the worst seat in the car. And it says something, maybe, that this wasn’t the little folding seat pinned in by a family of six’s luggage, but the middle.

I’ve spent so many hours in the middle seat of a car, enough at least to claim some knowledge of what makes it so weird and awful. It’s not just the lack of space, or the awkward question of where to put your feet. In the middle seat, more than any other, you’re beholden to the movements of the car, surrendered to its speed and turns, stops and starts. Nothing to hold on to, or lean against, open to an unobstructed view of the peeling road. You feel this on a long drive, it has a kind of rhythm that settles into your tensing muscles. And unlike the front passenger, the person in the middle can see through the rear-view mirror, accessing a distorted version of the strange, simultaneous perspective of front and back, what’s coming and what’s been—but without the driver’s agency of bringing that motion into being. It kind of feels like those hyper-budget roller coasters built around the millennium that just attached a cart to what was essentially a mechanical bull, projecting footage of a real ride ahead while the jerky machinery buffeted you about. In the middle seat, you’re being taken somewhere. And though you know what’s immediately in front and immediately behind, the ability to stop or change direction is out of your hands. It’s someone else’s ride, you’re just on it.

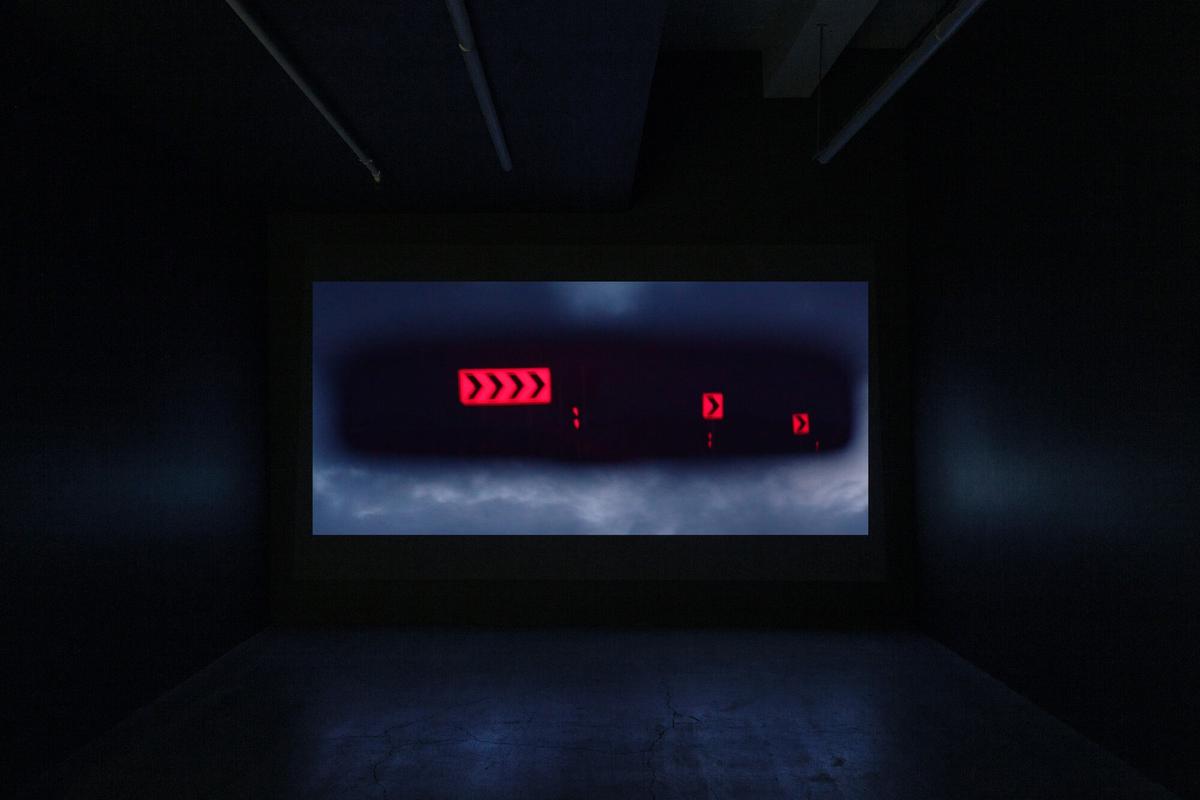

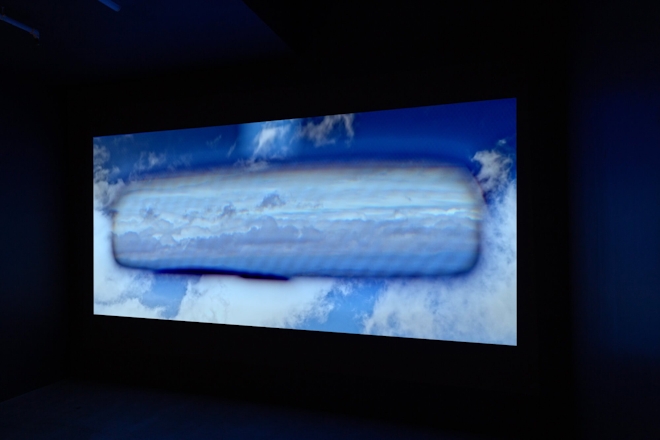

Installation view of Grant Priest CAN (2023), Enjoy Contemporary Art Space, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, 2023. Photo by Cheska Brown.

This is the memory and sensation I’m first drawn to when viewing Grant Priest’s CAN (2023), the contradictions of a certain kind of passenger perspective—the claustrophobic eye of the middle seat taking in too much information. It’s a work of the road, of driving and being driven, rich with visuals that can’t help but feel juxtaposed with the eye that sees them. Entrapment and enclosure met by the cultural codes of driving and the open road.

There’s no story in CAN, no obvious narrative arc over the course of the video. Instead, there are inflection points, moments of deviation from what Priest sets up as a kind of baseline for the work. That norm is this claustrophobic eye, impossible and occasionally omniscient, that we adopt for the video’s duration. Priest has paired forward- and backward-facing footage, placing the latter in the softly delineated shape of a rear-view mirror across the breadth of the screen. Rather than the middle seat, our view is pitched up and forward, almost as if kneeling above the centre console, just centimetres away from the mirror’s glass. The eye is fixed, unblinking. All that changes is what it can see—the reverse view in the centre, the fragmented forward in the periphery.

It’s someone else’s ride, you’re just on it.

Installation view of Grant Priest CAN (2023), Enjoy Contemporary Art Space, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, 2023. Photo by Cheska Brown.

The specific roads travelled in the work are important, but I want to think about roads more generally for a moment, where they’ve landed in our cultural imagination. We love roads. We vote for roads. Highway building was such an important aspect of the Key Government’s pitch for a revitalised New Zealand that, just months after taking power, they announced an initiative of seven Roads of National Significance—with the fabulously self-important acronym RoNS—for prioritised funding and construction. A decade later, the Sixth Labour Government soaked up the uncompleted RoNS projects into their soft-tech-sounding New Zealand Upgrade Programme. They’re still not all finished. Initiatives like RoNS and its successors have proven we’re pretty bad at actually building roads—over budget by millions, off schedule by years. But building roads is hard and boring work. The magic isn’t in the asphalt of a new highway or the chipseal of a rural road. It’s in the image, the potential, the romance. Roads as dark arteries ferrying commerce through the expanse of Aotearoa—slick passages for making an economy faster, sleeker. And the economic fantasy is always augmented by another, the one automobile companies are convinced can only be conveyed with desaturated wide shots of lone cars travelling faster than legally permissible through mountainscapes. You know, the road.

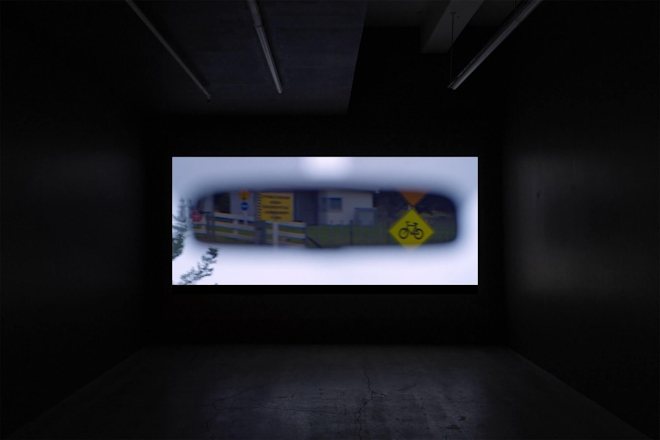

Installation view of Grant Priest CAN (2023), Enjoy Contemporary Art Space, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, 2023. Photo by Cheska Brown.

These fantasies cling to every culture built around a motor vehicle, but very few are locally grown. There’s a particular brand of American heritage that sticks to our roads. From the automobile industry and its concomitant propaganda apparatus, sure, but also film and television, music, popular and exhibited art. Essentially all of the sticky tendrils of soft imperialism that course across the Pacific and embed themselves in the roads of Aotearoa. Operating in this theatre of cultural inheritance, the road offers a contemporary symbolic equivalent to the Romantic poet’s lust for picturesque nature—an Other to the perils and pollutants of busy urban centres. The road as escape, the road as gendered independence and virility, as freedom. The road as an awfully white, awfully landed marker of progress and moral good.

The fantasy awakens at times in Priest’s work, and purposefully so. Throughout the video, there are points when the twin visions of CAN slip into incongruity, momentarily abandoning reality for something slightly more interesting. The boundaries of the two visions blur, angles contradict each other. The rear-view mirror remains fixed while the peripheral view pans, searching out something else. There are possible moments of revelation, the sensation that the two feeds are showing two totally different places, at different times. But these effects are all produced by one camera—Priest’s lens is mounted on the rear seat to simultaneously capture both forward and backward views—a mechanical fantasy as fixed in place as the roads the camera moves over. The most extreme shift comes when one view opens on an expansive blue sky, soon followed by the other. In contrast to the normal tone of the work, this sequence almost feels silly, a little camp. It’s like the final scene of Grease, Danny and Sandy flying off in a cherry red convertible, fulfilling the promise of the road by breaking free of it entirely.

There’s a particular brand of American heritage that sticks to our roads ... [its] tendrils of soft imperialism that course across the Pacific and embed themselves in the roads of Aotearoa.

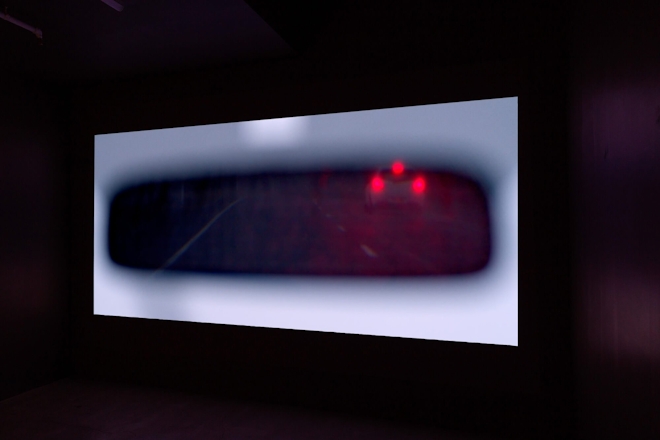

Installation view of Grant Priest CAN (2023), Enjoy Contemporary Art Space, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, 2023. Photo by Cheska Brown.

Or like Thelma & Louise. I remember first watching that final scene in a media studies class in high school. Geena Davis and Susan Sarandon driving off the cliff’s edge, hands entwined, me utterly failing to get it. I thought they’d lost, that the whole film had kind of been for nothing. Of course, the magic of that ending is how in that last chase through the desert and final plunge, the two were momentarily, but genuinely, free from the legal, domestic, and brutally patriarchal systems that entrapped them their whole lives. It’s a road movie where freedom is found by ditching its nominal structure all together. Nothing about highway fantasies is ever that simple.

Alluring as it is, the fantasy of the road tends to run up against the realities of its object. The irony of the road in the context of its connotative power is what a restrictive and prescriptive system it represents in the real world. Roads are fixed, unchanging, ceaseless repetitions across the same course. Whether driving, back in the middle, or perched in the impossible—and equally fixed—gaze of Priest’s camera, roads will trap you, and keep you to themselves. There’s the pull again. Freedom and captivity, open and closed, fluid and fixed. Maybe there’s a dialectic to find in those binaries, but they might better serve as a simple reminder that roads—here or anywhere—aren’t autonomous nor chaotic. They’re systems, built on systems, that can both expand our sense of place and constrict it into a narrow vision of use and re-use.

Installation view of Grant Priest CAN (2023), Enjoy Contemporary Art Space, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, 2023. Photo by Cheska Brown.

While CAN lacks a start or finish, it does have two poles. The roads we see throughout the video are those between Tongariro/Rangipo and Mount Eden prisons. The choice of these two carceral locations, and the work’s title (slang for prisoner transport vehicles), is what plays off the uncomfortable eye of the camera to give the video its final and crucial tension: the dynamic between what we think roads might be and what they really are. The central position of the camera and the exaggerated function of the rear-view mirror aren’t there to do anything so awkward and didactic as place us in the position of a prisoner. That’s not this video’s job, and certainly not what it’s trying to encourage. Nor is it to equate roads with prisons; there are thematic links but to make them any stronger would be pretty specious and icky stuff. The sum of the form and content is all so much middle seat—the bodily feeling of being taken somewhere, on these roads.

Because roads have a sort of inevitability and permanence built into their mythology it becomes harder to imagine them as objects with histories. But it’s their function within historical systems that shapes what they are and where they go. I think a lot of us assume that roads are laid out in the fastest or most efficient way to transport cars and trucks. Some are, especially newer highways, but even these are negotiated by human systems, such as the limits of compulsory acquisition. Older roads bear the traces of older systems. In much of the North Island, the bones of our current road networks were paved over paths cut by colonial military forces in the nineteenth century. Maybe the most famous is Great South Road, which swept from Tāmaki Makaurau into the Waikato in order to better prosecute Grey’s war on the Kīngitanga. But the North Island is full of such routes connecting Pā, colonial forts, and prison camps. The drive from Mount Eden to Tangaroa/Rangipo connects many. We re-enact those marched steps at breathless speed on the open road, point to point to point.

Installation view of Grant Priest CAN (2023), Enjoy Contemporary Art Space, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, 2023. Photo by Cheska Brown.

There’s a moment in the middle of CAN where everything slows down outside Mount Eden. The car turns, comes to a halt. Shots linger. It’s all a bit sinister and Karma Police. Viewpoints align and focus on tilt-slab and barbed wire. The score, which has only barely been present, comes hissing into the foreground. And then the car moves on, back to the road, and the ever-watchful eye moves with it.

CAN by Grant Priest was on view at Enjoy Contemporary Art Space, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington from 29 April to 27 May 2023.

Lachlan Taylor is an arts writer. He is studying towards a PhD in Art History at the University of Texas at Austin.