What does it mean to seek a home, a sense of belonging? I am writing this in Te Whanganui-a-Tara, following the Toitū Te Tiriti Hīkoi on 19 November, in which an estimated 50,000(1) people showed up in person to assert their commitment to Te Tiriti o Waitangi—the document that establishes the relationship between Māori and the British Crown—and in effect, gives Pākehā the right to be here, to call Aotearoa home.(2) This collective, vocal, and physical response to the Treaty Principles Bill, which proposes a diluted reinterpretation of Te Tiriti under the guise of 'equal rights', is a surging contemporary expression of the significance of the partnership historically formed through Te Tiriti.(3) Home is somewhere you have the right to be, either as tangata whenua in connection to the whenua, or as tauiwi under Te Tiriti. In this sense, Te Tiriti itself could be likened to a shelter.

In 'What it means to be at home in this land,' a 2022 text by Moana Jackson that I re-read over the course of Homing Instinct, speaking specifically about homelessness, he suggests that we have not yet clarified what it truly means to be at home in this land, something that goes deeper than having a house. Jackson expands on how Te Tiriti offers everyone the chance to find "'he whakaaro kāinga tika' … a righteous sense of being at home … an understanding of what is tika and what is appropriate and right in this land."(4) The Hīkoi felt like we were collectively walking in that direction: to be at home in this land means, for tauiwi, actively acknowledging the core relationship that makes this possible.(5)

Homing Instinct began with a conversation about housing inequalities in Aotearoa. It evolved into an international touring exhibition with moving image commissions by artists Ari Angkasa, Ananta Thitanat, and Kahurangiariki Smith with Buntheun Oung, accompanied by an existing work by Dieneke Jansen. Developed through an informal process by curators from Aotearoa (Mark Williams and myself, CIRCUIT and The Physics Room), Bangkok (Mary Pansanga and Sathit Sattarasart, STORAGE Art Space), and Naarm Melbourne (Channon Goodwin, Composite), Homing Instinct set out with a simple intention: to bring together these individual artists’ responses to ideas of housing, home, and belonging, grounded in their local context and personal experience. A wider ambition of the project was to contribute creative thinking, narrative, and imagery to existing conversations within our geographic region about what it means to be at home or belong, and about identity in connection to place. Selected through an open call to their local community by each of the commissioning organisations, each of the works in Homing Instinct ultimately spoke from a distinct perspective, with points of convergence around diasporic and indigenous identities, and family histories.

,-2021_5.jpg)

Dieneke Jansen, This Housing Thing (2021). Digital video with sound, 18 mins 37 sec.

The initial prompt for Homing Instinct was sparked by watching Dieneke Jansen’s This Housing Thing (2021), a work that documents all of the houses Dieneke has lived in, with commentary by the artist reflecting on conditions of inherited privilege, and the shifting political contexts in which her specific experience of housing is embedded. For Dieneke, the right to housing and the history of social housing in Aotearoa has been the long-term impetus for her art practice, with projects typically unfolding in collaboration and often outside of traditional gallery spaces. Speaking with the artist, our conversation moved from the politics of access to housing in Aotearoa, to the ways other local artists have responded to concepts of home and belonging, including ideas of displacement, diasporic identity, whakapapa, and return. Here in Aotearoa, where the reality of housing need is increasingly stark—right now there are 22,923 people on New Zealand’s social housing waiting list(6), over 6000 people are without a place to stay every night(7), and over 40,000 lack safe, secure accommodation—the necessity of addressing the inextricable connection between these things, shelter, home, and a sense of belonging, is pressing.

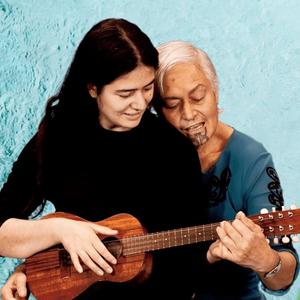

Kahurangiariki Smith with Buntheun Oung, Mā te Moana (2024). Digital video with sound, 14 mins 22 sec.

Evolving from the ideas worked through in this early conversation, each of the commissions took its own course. Kahurangiariki Smith’s work Mā te Moana (2024) is about the push and pull of one’s home(s), likened in the work to the arrival and retreat of ocean tides. A descendant of Te Arawa waka, Kahurangiariki made this work while in Rarotonga, living within swimming distance of where many ancestral waka departed for Aotearoa. She was looking out to the same horizon and waters as her ancestors did, spending time learning about the intersecting genealogical connections to the outer islands of Kuki ‘Āirani (Cook Islands). Kahurangiariki’s own narrative sits alongside the words of Buntheun Oung, who speaks of returning to his homeland of Cambodia. Film photographs documenting Buntheun’s journey are juxtaposed with phone footage and animated, chrome-coloured kaperua (symbolising the doubling of things, or infinite repetition) and takarangi (spiral forms). Sounds of waves crashing and karaoke nights with the aunties track Kahurangiariki and Buntheun’s travel between Rarotonga and Cambodia. The rhythm of this work is established through recurrent images of bodies of water: from Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwi seen from the beach in Rarotonga, to a swimming hole at Kahu’s home awa in Te Arawa, Te Wai Mimi o Pekehaua, to the glowing blue swell and glancing cerise of the ocean in the digital chapter of the work.

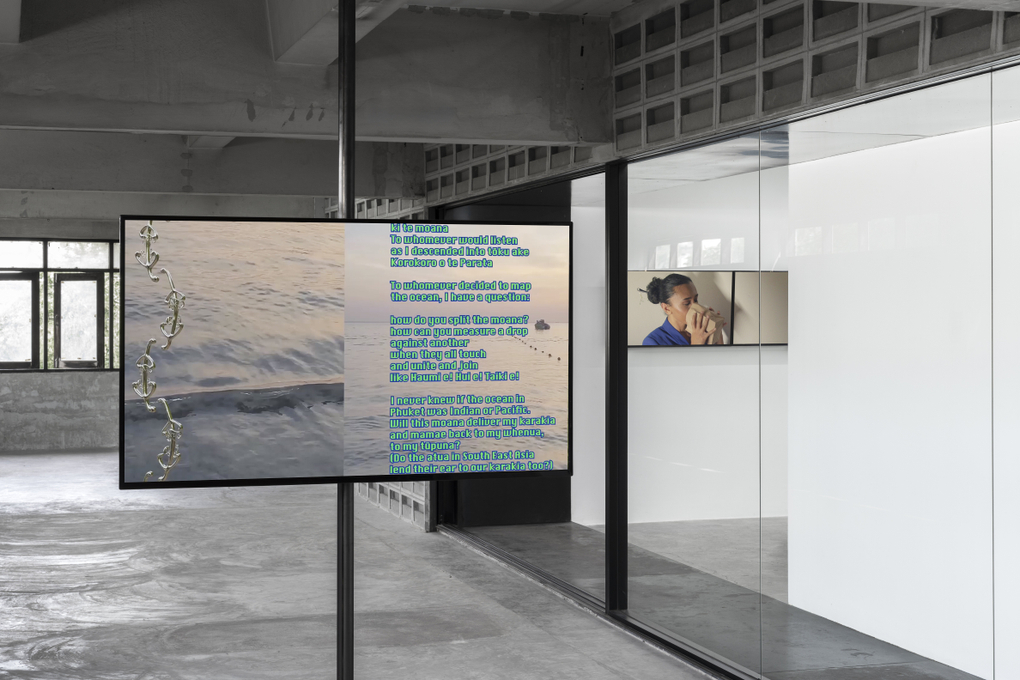

Kahurangiariki Smith with Buntheun Oung, Mā te Moana (2024) and Ari Angkasa, Quantum Leap (2024). Installation view, Homing Instinct, STORAGE Art Space, Bangkok, Thailand, 2024. Photo by Atelier 247.

Watching Mā te Moana in Bangkok, another body of water came into the frame. At STORAGE, this work was the first thing you saw as you entered the space. Behind it, and deeper into the gallery, a line of windows opened onto the surrounding neighbourhood. Two streets over, this takes you to a waterway that connects directly to the larger Chao Phraya river; go further south and you will reach the Gulf of Thailand; go east and Thailand’s coast meets the Andaman Sea. I’d recently learned about the khlongs, Bangkok’s historic canal system that intersects the Chao Phraya river at multiple points. The waterways were a primary mode of transport in the city as well as enabling shorter trade routes for merchants. While the introduction of roads in the late nineteenth century disrupted this network, the river still hosts thousands of commuters daily, as well as floating markets and riverside communities. Watching Mā te Moana in humid Bangkok—a city traversed by water and just two hours’ drive to the coast, from where you could sail all the way to the Pacific Ocean—was to become aware of the sea, and subtly brought the sense of Kahu’s ocean-navigating ancestors closer. It made me think about the myriad ways that a body or bodies of water not only connect people but can in themselves be home, too.

,-2024_2.jpg)

Ari Angkasa, Quantum Leap (2024). Two-channel digital video with sound, 17 mins.

Ari Angkasa’s Quantum Leap (2024) was made in collaboration with her sister, the filmmaker Serena Arsletta. A satirical remake of an airline safety video, the two-channel video combines Ari’s video collage and performance art practice to address the aviation industry's role as an arm of the state in global politics. Using archival footage from the European Union’s ban on all Indonesian airlines in 2005 and the series of aviation scandals plaguing Indonesia preceding it, along with family archives on VHS, Quantum Leap sees Ari perform the unreliable narrator embodied in a flight attendant. With her hair in a French twist and a classic kebaya uniform cinching her waist, the artist splits into two characters who speak different languages. Moving in and out of linear narrative, synchronisation, and image resolution, the work seeks to make sense of queerness, what it means to belong, and transitional dysphoria in the context of diaspora.

Ari Angkasa, Quantum Leap (2024). Installation view, Homing Instinct, The Physics Room, Ōtautahi Christchurch, 2024. Image by Janneth Gil with Valeria Sanchez.

Ari returned to Jakarta from Naarm to shoot the film, and later described to me the intensity of this process, working in densely populated public space and with frequent interruption. In the final edit, these scenes, often presented with a recurring cameo motif in which the narrator appears, are integrated with others that have a more formal choreography—the cool blue geometry of a swimming pool filmed from above, or completely empty space, the moon-like expanse of airport transit lounges. Quantum Leap is edited as two channels; sometimes a single image flows seamlessly across both screens, at others there is doubling or repetition, a form of visual rupture. In this way, the work evokes the often-dissonant layers within a non-normative sense of belonging, and the ways that asynchronous or poetic narrative and liminal public spaces may offer the possibilities of rest, solitude, or even ease.

Ananta Thitanat, Siam (2024). Digital video with sound, 13 mins 18 sec. Installation view, Homing Instinct, STORAGE Art Space, Bangkok, Thailand, 2024. Photo by Atelier 247.

In Siam (2024), Ananta Thitanat asks her father about the stories behind the Siam Cinema, a commercial movie theatre located in central Bangkok which was their home for much of the filmmaker’s childhood. The cinema was destroyed by fire during an anti-government Red Shirt protest in the city in 2010. Seeking to recall and consolidate fragmented memories of her destroyed home, Ananta creates a series of restless drawings. On the soundtrack, we hear her father’s recollections of their time spent living together at the theatre, and of his co-workers' lives that revolved around the Siam.

At The Physics Room in Ōtautahi, Ananta’s work was installed flanked by curtains, so that it was viewed from inside a darkened, triangular space. Echoing the shape of a projected light beam, this set up meant that you sat inside of an intimate space between the projector and the image, almost as if you were inside of the film itself. While the work existed in two-dimensional drawings and through audio, documenting memories of a home, it also compelled the viewer to physically occupy a related form of architecture. That is, in learning about what it was like to work and live at the Siam in the past, the viewer temporarily inhabited the cinema-as-home or shelter in the present.

Ananta Thitanat, Siam (2024). Installation view, Homing Instinct, The Physics Room, Ōtautahi Christchurch, 2024. Image by Janneth Gil with Valeria Sanchez.

Homing Instinct has now been shown in Ōtautahi at The Physics Room, Te Whanganui-a-Tara at Enjoy, Bangkok at Storage, and Naarm at Composite. Some, but not all of the artists and curators have met in person, and language translations (most of the works involve text or spoken narrative) have been undertaken, with all the attendant complexities. As such, the works have shifted through states of belonging and meeting for the first time; hosting and being hosted; being located and in transit. While all of the new commissions were initiated and developed with the awareness that they would move across different cultural contexts and physical spaces, it’s notable to me that they each resist easy consumption in different ways. Each relies on acts of translation, requiring that difference is first acknowledged, and then that some work is done to initiate a relationship within the new context.

.jpg)

Kahurangiariki Smith with Buntheun Oung, Mā te Moana (2024). Digital video with sound, 14 mins 22 sec.

The script for Kahurangiariki’s in particular, originally written in both te reo Māori and English and including points where the two languages are used interchangeably, in the manner of some speakers in Aotearoa, resulted in a decision by the Thai translator to leave the intermittent Māori words as they stood, relying on surrounding context to situate and give meaning rather than direct translation. This meant that while the Thai translation was unable to be comprehensively understood by all but a few readers, at the same time, however, it retained the original text’s multivocality, invoking Indigenous language connections going back in history.(8) In Ari’s work, its deep nonlinearity meant that 'following' the story was not possible, and a slick aesthetic experience was frequently disrupted with pixel-stippled footage bearing its era-specific timestamp. Ananta’s work, while exquisitely cohesive aesthetically, hinges on a double-ness, in which the narrative about a historical cinema space became visually fused with that of the workers' lives running things 'behind' the scenes. Nonetheless, the filmmaker and her father, protagonists in the story, remain invisible to us. Finally, returning to Dieneke’s work again in the gallery in Bangkok, I was newly aware of its insistence on the political necessity of a plurality of definitions of home, and of allowing oneself to change over time. Tracing the artist’s movement from her birthplace in the Netherlands to an adult life spent predominantly in Aotearoa, and between squatting to house ownership, the work also tracks the growth of a political subjectivity. Places, things, people, and time, change us, the work suggests, and home is an equation of all these things; we exist in a state of reciprocity.

,-2021_2.jpg-(1).jpg)

Dieneke Jansen, This Housing Thing (2021). Digital video with sound, 18 mins 37 sec.

In Homing Instinct, each of the works disrupted seamless transition between the contexts in which they were hosted and screened, reminding me how home is fundamentally a relative thing—that is, based in the navigation of differences and distances. Walking towards Parliament, surrounded by the multiple languages of those who call Aotearoa home under the relationship embedded in Te Tiriti, I thought again about the idea of a 'homing instinct', defined as the inherent ability of a creature to navigate or return home through unfamiliar routes, perhaps across extreme geographical distance or historical dislocation. A deep, gut-based need for home, which brings us back into step. This is not because we all understand home in the same way; rather, it’s because we know that it matters to live in relation with and to each other.

Abby Cunnane is a writer and curator based in Aotearoa. She is the co-editor of The Distance Plan, a journal on contemporary art and climate change with Amy Howden-Chapman, and previously worked as the Director at The Physics Room, Ōtautahi (2021-2024).

,-2024_4.png.png)