I am in Ngāmotu New Plymouth, inside the distinctive scoop of the Govett-Brewster’s wavy, concrete walls, walking up the gentle gradient that weaves in and out of the exhibition spaces in the middle of the building. I am here to see a big new show—Interlaced: Animation and Textiles—that unrolls, like a bolt of cloth, through the interior and exterior galleries of the Govett’s extension.

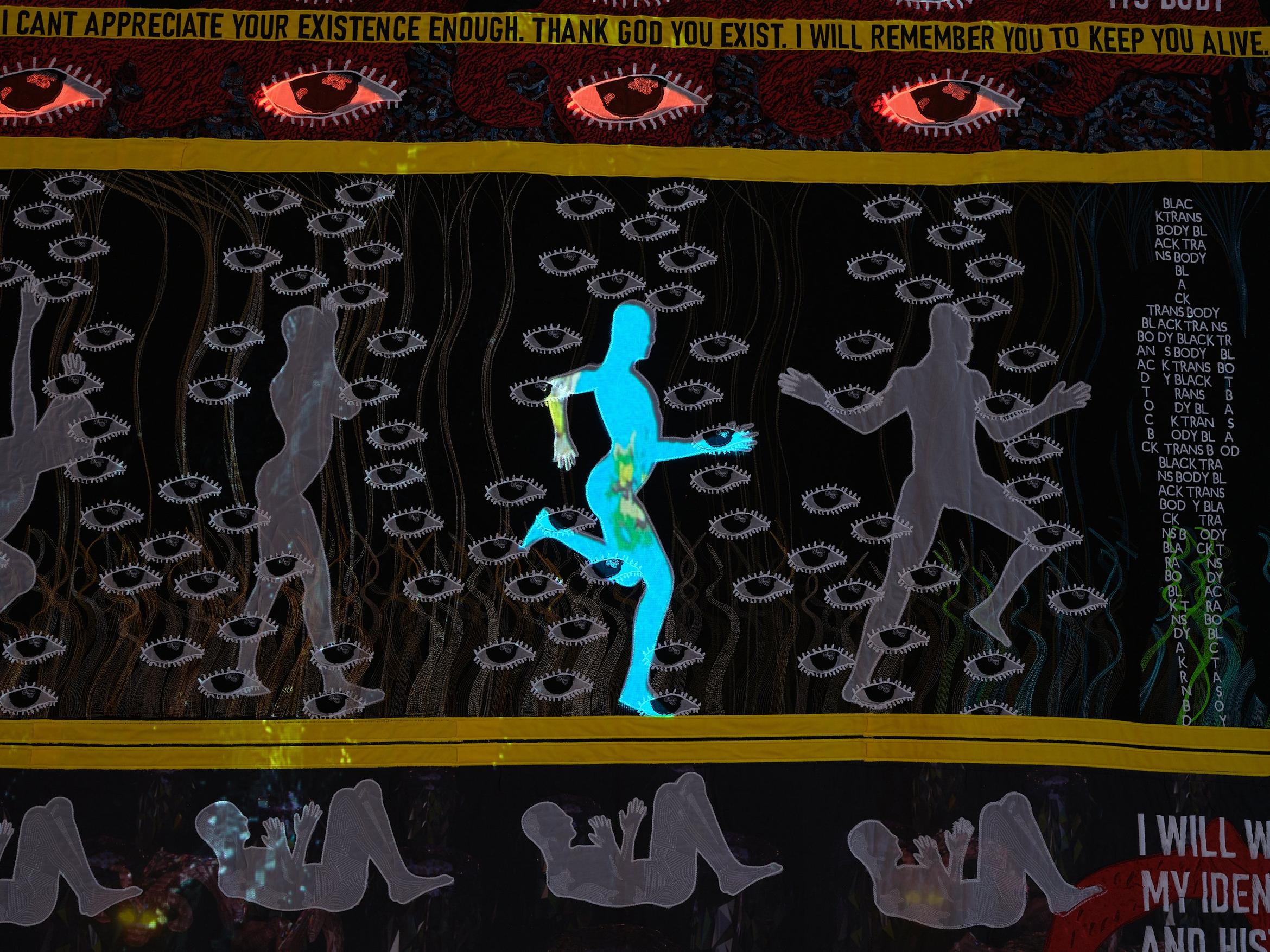

First, I hear waves. Then, I see Peau Lalava o Moana—The Moana that Binds Us (2024), Sione Faletau’s new video work, on the far wall of the first gallery, reaching up the full height of the tall space. Faletau listens closely to the world. He records sounds from many different places—alleyways, city roads, and, in this case, the Pacific Ocean rushing against the shoreline near the Govett-Brewster—and translates these into moving, responsive patterns influenced by the kupesi forms of Tongan ngatu (bark cloth) and lalava (architectural lashing). This multisensorial work is an impressive welcome to Interlaced; it acts as an anchor for the show, as well as performing a transformation: the hard concrete of the Govett’s walls becomes lush, breath-filled material. Though this is an expansive group show of international and Aotearoa-based artists, the sound of the waves washing through the galleries locates the exhibition in Ngāmotu New Plymouth, to this specific corner of the world, and to histories of Polynesian pattern-making, fabric, and architecture. The work introduces ideas that recur throughout: a medium becomes another medium; stillness moves; fabric communicates cultural memory and political potential; and repetition creates meaning.

Sione Faletau, Peau Lalava o Moana—The Moana that Binds Us (2024). Moving image, sound, 5 min. Installation view, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery | Len Lye Centre, Ngāmotu New Plymouth, 2024. © and courtesy of the artist. Photo by Sam Hartnett.

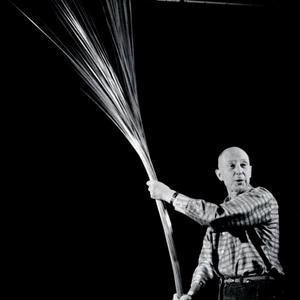

These are all ideas that danced in Len Lye’s brain, and the influence of his work (known by the other artists in the show, or not) permeates Interlaced. The Govett is the repository of Lye’s work and archive; the institution recreates and exhibits his work, preserves his archive, and leads scholarship about his art. Lye’s multimodal art can be curated in many directions and as the cultural and political contexts outside the Govett-Brewster change, the question of how to situate his art—which wriggles endlessly at the heart of this public gallery—remains. What does Lye’s work mean now, in 2025? What frameworks does it provide for contemporary artists? What questions do these artists ask of Lye? And what questions does his work ask in return?

Interlaced positions Lye’s work within the two under-addressed art histories of textiles and animation. Alla Gadassik, an Associate Professor at Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver, was appointed as the Govett-Brewster’s International Film Curator in Residence in 2022 and this show is the result of her scholarship at the Len Lye Centre. Gadassik correlates the failure of Western art history to value and discuss fabric and textiles arts with its similar omission of animation as a medium worthy of study. Both of these practices have been considered naive, feminine, and amateur by Western institutions and scholars in positions of taste-setting and academic power.

Gadassik’s exhibition brings these two art historical absences together and draws connections between the mediums that may, at first, seem distinct from each other. Interlaced uncovers new histories and lines of enquiry: artists interested in the tactile qualities of analogue film; artists aware of the political implications of the clothes we wear and the cloth that warms us; artists entranced by the interplay of weft and warp. Throughout, Gadassik emphasises the repetitions that create form, image, and pattern in both animation and textiles. In analogue film, the illusion of movement is created by the repetition of many small, still images whirring through the projector. In textiles—weaving, quilting, knitting, and embroidery are some examples from a myriad of techniques on view—images are created through the repetition of stitches and links. Small, sequential acts accumulate to form a larger whole and this way of creating meaning and image has both metaphysical and material implications that are traced across the show.

Installation view, Interlaced: Animation and Textiles, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery | Len Lye Centre, Ngāmotu New Plymouth, 2024. © the artists Marguerite Harris, Kelly Egan, Jennifer West, Sabrina Gschwandtner. Photo by Sam Hartnett.

Paris-based American artist Marguerite Harris takes analogue film and mounts it in a big spiral on the wall in her work Sewn Film (2016–2024). The film has been run through a sewing machine and is stitched with coloured thread that interrupts and augments the many small images. Film, in Harris’s work, is a sculpture; a fabric background for the foreground conversation of the thread; a large octagon that could itself be one patch in a bigger quilt. Harris compares and combines the process of fabric spooling out from the punctures of a sewing machine and film skimming through a projector, both technologies that consume small increments to manifest a larger whole. Exhibiting the repeating frames that create moving image can still time and inhibit film’s innate drive for sequence and linearity. Harris plays with this by mounting film onto the gallery wall and inviting us to look at it slowly, and side on. Similarly, Canadian artist Kelly Egan’s two works Athyrium filix-femina (for Anna Atkins) (2016) and c: won eyed jail (2005) literally stitch film into large quilts that hang from the ceiling. The repetitive images are patched into diamonds, rectangles, and squares. I walk around these and look through them; the images are not only static and non-sequential, but are transparent—I can see other visitors walking around the exhibition on the other side.

The "Anna Atkins" of Egan’s title was a nineteenth-century English botanist and photographer who created many bright-blue cyanotype prints of algae. Atkins's work is both beautiful and scientifically useful, and Egan used Atkins's original cyanotype recipe to expose the 35mm filmstrip in her quilts and moving image work. Egan’s work is a homage to and reclamation of women who have been excluded from histories of photography and the pervasive stories of how images were created and circulated in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Egan's and Harris's work, curated together in the first gallery of the exhibition, introduce a feminist thread that binds the show.

-image-sam-hartnett-(2).jpg)

Marguerite Harris, Sewn Film (2016-2024). Stitched celluloid, moving image transfer, dimensions variable. Installation view, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery | Len Lye Centre, Ngāmotu New Plymouth, 2024. © and courtesy of the artist. Photo by Sam Hartnett.

In her 2023 book, Through Shaded Glass: Women and Photography in Aotearoa New Zealand 1860–1960, Lissa Mitchell discusses the female workforce of colourisers and retouchers of photographs, and the demotion of these practices to "crafts" in the hierarchy of image production in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Mitchell writes that from the mid-twentieth century, photographic histories have focused on "the photographer as a masculinised artistic figure taking images that conveyed vision and ideas. Meanwhile, the skills employed in retouching, colouring, printing and mounting photographs became characterised as feminine roles associated with other activities done by hand, such as needlework, and increasingly devalued."(1)

Many of the same practices were applied in the early production of film. Interlaced celebrates this work and cleverly connects the handwork of colourisers and stencil-dyers with the feminised labour in garment factories and textile mills. In the centre gallery, women pose and model clothing in a film illuminated by glowing and surreal colour. Mode Uit Parijs, one of the fashion newsreels made by Pathé film studio between 1911 and 1925, showcases the hand-tinting and stencil-dyeing methods of the women employed by the company. Their work treated the celluloid film as a kind of cloth to be coloured and reworked, so that the resulting moving image could itself market clothes and fabric to fashionable women.

Pathé Studio, Loïe Fuller (1905). Still from film, silent, 1 min 5 sec. Courtesy of the British Film Institute National Archive.

The show leaps from this history of film-as-fabric, to contemporary works of filmed fabric. Inside the nearby darkened gallery (described in various exhibition-related texts as, adorably, a "viewing pocket") American artist Jordan Wong’s 2018 work Mom’s Clothes shows material filmed up close and abstracted into hundreds of tiny loops and stitches; the patterns of horses and tigers from Wong’s mother’s blouses and skirts bound and morph across the screen. These abstracted, moving patterns are accompanied by a narrator who speaks about the life-giving company of queer friends and the pressing judgement of the heteronormative world. Mom’s Clothes is both gentle and angry. It makes me think of being a kid pressed up against my mum’s body—something’s gone wrong and I’ve hugged her; the known comfort of her and the familiarity of her clothes.

Jordon Wong, Mom's Clothes (2018). Moving image, sound, 5 min 34 sec. Courtesy of the artist

Mom’s Clothes and works by Ishu Patel and Ng’endo Mukii are screened alongside two of Lye’s well-known films, Color Cry (1952) and Kaleidoscope (1935). There are many aesthetic similarities between the historic and contemporary works, as abstract colours and shapes zoom and dance energetically across the screen. Lye made his films by various direct techniques; he used cardboard and metal stencils, gauze, and other patterned materials to imprint celluloid, examples of which are exhibited in the show. Lye’s interest in the kinetics of abstraction, the potential of animation, and the physical manipulation of film, are springboards for many of the ideas in Interlaced.

There is a tension, though, in positioning Lye as an originator in this show. Many of the contemporary artists in Interlaced explore animation and textiles as ways to build familial connection, enrich domestic life, and revive previously suppressed cultural practices. In 1944, Lye moved from London to New York to pursue a career opportunity. He left his wife and two kids in war-torn London, in the middle of The Blitz. As Jane Lye, his wife, said, "I had long been accustomed to the fact that his work was the most important thing in his life…."(2) A man abdicating his childcare and domestic responsibilities to make his art is the rule rather than the exception of art history. The contemporary work in Interlaced emphasises women’s work, the creative potential of domestic life, suppressed knowledge, and minority groups’ struggle for self-determination. There is a distance then, between Lye’s work, with his modernist interest in form and movement, and the politically and socially inflected work by contemporary artists here—people who can’t move through the world so unencumbered by responsibilities and relationships.

Vaimaila Urale, O Le Sami Po Uliuli (2024). Digital printed fabric, 357 x 643 cm. Installation view, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery | Len Lye Centre, Ngāmotu New Plymouth, 2024. © and courtesy of the artist. Photo by Sam Hartnett.

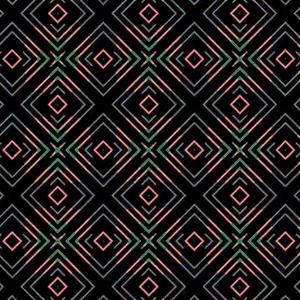

Lye spent time in Sāmoa in the 1920s and the art he saw and the people he met there greatly influenced his thinking and work. In the Govett, Sāmoan-born, Aotearoa-based artist Vaimaila Urale’s beautiful new commission, O Le Sami Po Uliuli (2024), brings contemporary Sāmoan politics and environmental concerns into the exhibition. The work towers above you; it is floor-to-ceiling and made up of many rectangles of bright blue digitally printed fabric. Here, Urale uses the simple forms of ASCII characters—a standard encoding format for electronic communication—to create wave and stitch-like patterns that are influenced by Sāmoan tatau (tattoo) and tapa (barkcloth). ASCII characters were developed so that many computers could talk to each other. They are repetitive and international. Urale, however, complicates this universality by using the symbols to recreate Sāmoan patterns and stories that reference specific knowledge and events: one pattern symbolises the recent sinking of the HMNZS Manawanui on a reef off the coast of Sāmoa. Here is the bounce then, in this show, between global and local. O Le Sami Po Uliuli is diagonally across from Faletau’s sensuous Peau Lalava o Moana, and I feel the two works reaching out, listening to each other across the intervening space.

Leaving the cool interior of the Govett, the ocean sounds of Faletau’s art following me, I scrunch my eyes at the bright sun. I walk up the street and my reflection follows me; I am both neatly doubled and strangely misshapen in the gallery’s wavy, mirrored exterior. Interlaced similarly doubles the mediums of animation and textiles to see what new knowledge might result when we look sideways at linearity. Two art historical absences become a new presence.

Interlaced: Animation and Textiles was on view at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in Ngāmotu New Plymouth from 7 December 2024 to 27 April 2025.