Enshrined within the ornate walls of Tāmaki Makaurau’s Pah Homestead, from its seat amid the manicured, imported flora of Monte Cecilia Park, is something that belies its Victorian facade: in two darkened rooms atop the 19th-century villa, six “river exposures” and a video essay by Kate van der Drift muddy the modes of seeing that have historically structured ways of engaging with the land, taking to task the colonial conventions that have dictated both the representation and physical organisation of land in Aotearoa.

In Listening to a Wet Land, van der Drift seeks to undo these histories of settler seeing, drawing on her extensive visual research conducted in the Hauraki Plains. The subject of her recently completed MFA, the Plains are an area van der Drift has been visiting regularly since 2017, where she has undertaken numerous recordings through sound, video, Super 8 film, and the camera-less images she has termed “river exposures”. These latter images have become somewhat iconic of van der Drift’s practice, symbolising the broader impetus of the Hauraki Plains project. Situated in the heavily comprised ecology of the Plains, where the water quality is among the worst in the country,(1) van der Drift’s exposures seek to respond to the deep embedment of colonial history not only within the land, but also within the conventional methods of its visual representation.

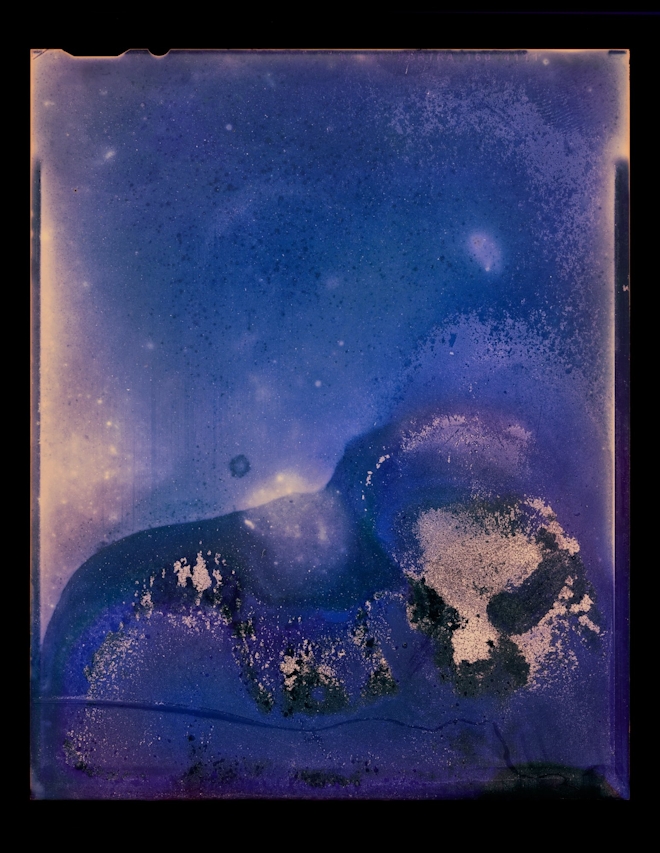

Focusing on the Piako awa, van der Drift was interested in exploring methods that would allow the river to “write its own image”,(2) thereby minimising the level of human intervention, and the attendant representational baggage, in the creative output. Over the course of her research, she arrived at the method of producing – or rather facilitating the production of – “river exposures”, in which van der Drift places photographic film in lightproof containers in the tributaries of the Piako awa and leaves them submerged for periods between two and four weeks long, depending on the season and the phases of the moon. Van der Drift’s “collaboration”(3) with the river then takes form as the emulsion of the negatives is slowly eaten away at by a combination of farm run-off, saltwater, sediment, bacteria, and algae, resulting in a “durational accretion”(4) inscribed by the chemical composition of the water. Retrieving the negatives from the water, van der Drift then hand-develops the film in a darkroom before printing them on photographic paper and digitally enlarging them, resulting in otherworldly, purple-blue prints whose forms occupy that uncanny space between the extra-terrestrial and the deep oceanic.

Kate van der Drift, New Moon to New Moon, August 2019 II (2022)

The exhibition’s video essay, Dazzled (Numbed?) by a Myth (2022), also emerged from van der Drift’s research in the Plains, and like her river exposures addresses the heavily compromised ecology of the area, as well as the epistemological splits – nature/culture and otherwise – that have underwritten it. Complementing the exposures as direct images of pollution, the film meditates on the entangled social and ecological histories of the Plains and their philosophical ramifications through two narrated readings: the first, excerpts from a chapter written by ecologist and writer Geoff Park on the colonial history of the Plains and the second, a letter by van der Drift to Barbara Hurd, author of Stirring the Mud: On Swamps, Bogs, and Human Imagination (2008). Comprised of slow pans over the Plains interspersed with footage moving through wetlands and over rivers, Dazzled (Numbed?) by a Myth is devoid of any visual human presence, constituted instead by a combination of narrated voice and imagery that reveal the land to the viewer while obliquely teasing out its colonial histories and future promises.

Kate van der Drift, Dazzled (Numbed?) by a Myth (2022)

Van der Drift’s interest in the Hauraki Plains as the site for her research is manifold and, like all people whose inhabitance of Aotearoa was forged through European settlement, deeply entwined with the colonial making of this country as “New Zealand”. Van der Drift’s personal attachment to the area is rooted in her grandparents’ migration to the neighbouring Waikato District, and her mother grew up at the southern boundary of the Plains, where her grandmother still lives. The project was also influenced by the Geoff Park chapter excerpted in the first half of van der Drift’s video essay, in which he explicates the definitive role the Plains have played in New Zealand’s colonial trajectory. Determined by James Cook as “the best place for a colony” upon his first voyage to the antipodes in 1769, the Plains are identified by Park as the origin of modern New Zealand: the site to which the country’s colonial identity as a utopia of self-sufficient agricultural industry founded on privatised blocks of land can be traced.(5) Van der Drift notes how her childhood was spent on low-lying dairy farms such as those that much of the Plains had been converted to during European settlement, and describes the deep sense of grief that marked her early visits to the area, when she had learned of the damage done to it through intensive agricultural development.(6)

In Park’s account, the Plains summarise the entanglements between founding colonial fantasy, total ecological transformation, and the foundational tenets of particular kind of ruralised, dairy-driven Pākehā identity. They also elucidate the role romanticised imaginings of land had in the physical re-organisation of New Zealand’s landscape. When Cook arrived in the Firth of Thames, England was undergoing a radical transformation in its social and economic approaches to land, as swathes of land that had been previously been commonly held were being divided, enclosed, and transferred to private ownership. Around the same time as this notion of land as an organised entity was developing, ‘landscape’ emerged as an aesthetic category, including in the form of the Picturesque, an aesthetic ideal of seemingly ‘natural’ landscape devoid of human intervention – and the organising principle for Pah Homestead’s grounds. Early painted representations of New Zealand also assumed these aesthetic codes, thereby transforming a foreign land into a legible object; and as ‘New Zealand’ took hold in European consciousness as a pre-industrial paradise of endless pastoral promise, its lands were being subjected to the same, radical organisation as those in England, reproducing the industrial-agricultural development its proponents were seeking to escape.(7)

As an artist, van der Drift is deeply aware of the role of representation in the colonial constructions of New Zealand, a kind of settler seeing that served to consolidate approaches to land as a bounded, proprietary entity. She is particularly aware of these colonial conventions in the context of photography, a nascent technology during the early colonisation of New Zealand that inherited many of the conventions of landscape painting, and later served as tool to legitimise colonial difference through the speciously objective genres of ethnography and tourism. Countering the ways in which these histories are implicated by photographic technology, van der Drift’s practice is underwritten by her pursuit of ways in which her subject, the awa, can represent itself, rather than be represented through predetermined modes of seeing. To do this meant moving “beyond the lens”,(8) or, indeed, doing away with it altogether; without a lens, the river exposures achieve a much more direct relationship with their subject, becoming “an emanation of that world, rather than a copy.”(9) The directness that van der Drift achieves through her novel approach to photography, however, is beyond the medium itself; being produced in the dark, the river exposures cannot really qualify as the 'light writing' denoted by photography’s etymology, as there is no light present during their development. Through their immersive making, the exposures bear a trace of their referent that is even more direct than the photographic index, the representational trace the technology of photography is so indebted to. In its absence, it is not the light that is writing, but the river itself – not landscape painting, but landscape that paints.

Installation Shot: Kate van der Drift, Listening to a Wet Land, Pah Homestead (2022)

Van der Drift’s video essay has a different relationship to the land whose representation it seeks to facilitate, in contrast to the direct materiality of the exposures. The nature of moving image is that it reinstates the lens that van der Drift’s exposures do away with, re-inserting the distance that is the historical condition of landscape seen, framed, and apprehended. In his book Theatre Country, Park writes about the Claude glass, a curved, palm-sized mirror that emerged during the late 18th-cenutry frenzy for Picturesque tourism, which enabled its users to view a landscape as through it were a painted representation but, in order to do so, required them to have their backs to the very landscape they wished to regard.(10) Dazzled (Numbed) by a Myth? attempts to eliminate this distance, not necessarily through the materiality of its medium, but through the material conditions of its making. More than simply engaging with the land through artistic processes – whether submerging film in its awa or otherwise – van der Drift’s project is the cumulative outcome of extended time spent in the land; much of the footage of the film was captured while she was with duck hunters or landowners, whom she befriended throughout her research, and who facilitated her experience of the wetland. The film can thus be seen as the result of the entangled relations that make up an ecology, giving voice not only to nature as river, but as the multiplicitous relationships that constitute it.

Installation Shot: Kate van der Drift, Dazzled (Numbed?) by a Myth (2022) as part of Listening to a Wet Land, Pah Homestead (2022)

Throughout her work, van der Drift seeks to surpass the modes of representation that have historically denigrated land to the status of apprehendable object, an aesthetic predetermination that aided the transformation of New Zealand’s natural environment and contributed to its ecological deterioration. Doing this has meant pursuing artistic methods that foreground of the agency of the land, thereby problematising representations of land that have historically relied on the perspective of the human agent, removed from nature, viewing nature as a bounded object. Van der Drift’s works, however, complicate this history of settler seeing in another way, which is through their relationship to visual illegibility, an un-seeing that undermines the agency of the human as an interpretative subject. This is primarily achieved through the works’ relationship to darkness, for which the colour blue stands as a kind of shorthand; the exposures, produced in darkness, emerge into light as blue, and the video essay begins in darkness, before panning slowly over a deep blue shoreline of early morning or evening, the distinction between land and water barely perceptible.

This blue of darkness is a blue of unknowing, and speaks to a key emphasis on illegibility in van der Drift’s project. In the second part of the video essay, van der Drift responds to Barbara Hurd’s treatise on swamplands as illegible bodies: essentially marginal entities whose unclear distinction between land and water refuses the definition required for easy reading. In the context of representation, this illegibility is recuperative; it scrambles the codified conventions that reify nature as an object of apprehension, resisting the interpretation of nature in the ways that have historically demeaned it. But this illegibility also provides a means of thinking about identity in New Zealand more broadly, in a way that is outside of the agri-industrial framework Park explains was set in motion by Cook’s first visit to the Plains. The history of landscape representation in New Zealand has been defined by a European impulse to separate, objectify, and illuminate, whereas the reality of being in this country as descendants of settlers is something that is more akin to the reality of swamplands – something darker, less clear, more prone to the ontological quandaries of wetness. As tāngata tiriti, it is an embrace of this illegibility, of not knowing, that is perhaps the most productive orientation to this land – one that may allow the land to speak, and us to listen.

Alena Kavka is a writer and art professional based in Tāmaki Makaurau whose interests span the intersections between contemporary art, writing, and public space.