Richard Frater speaks of Living Cities 2011- as a documentary film of sorts, and yet there is very little in the way of moving image work sequestered under this title.(1) To understand this we need to back-track to 2011 when Frater was commissioned by the Adam Art Gallery to undertake work towards a film about Wellington, work that eventually resulted not only in his rejection of the moving image as the representational frame for that commission but in the eventual migration of that specific film stock into a sculptural-relational work within Living Cities 2011-. More on this aspect later, but for now, it’s enough just to note Frater’s dogged relation to what he calls the “apparatus of cinema”, something he doesn’t necessarily negate the more he fine-tunes for his own ends.

It is worth here sketching something of the tableaux that composes Living Cities 2011-.

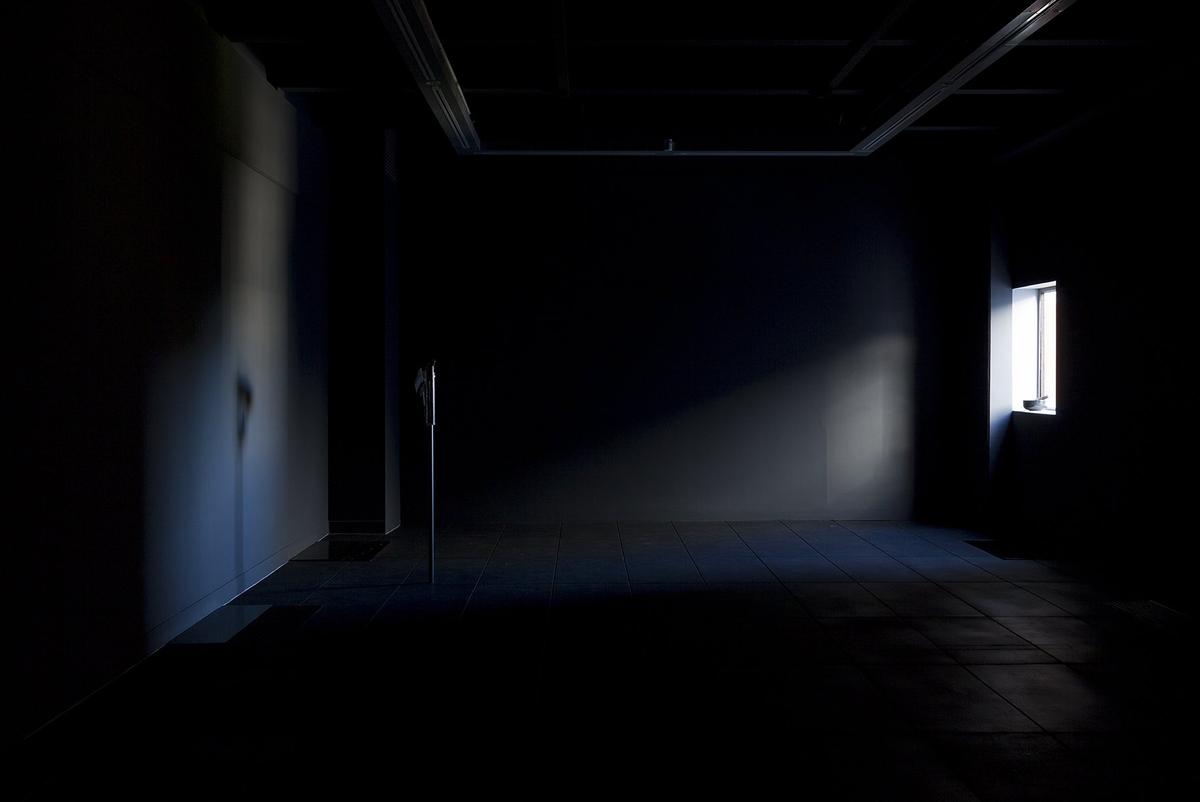

- The Adam’s Kirk gallery, typically their screening room has been altered to expose a pre-existing window. Upon the window’s ledge is a mortar and pestle that has had lead ground within it. Opposite this is a nail-gun and pedestal combo glistening in the light leaking from the aperture of the newly exposed window.

- Approximately 5 minutes up the road Frater has another exhibition space, this one with panoramic views of Te Aro valley. Included inside is another nail-gun and pedestal combo, a box of lead-capped roof nails and a sound-work by Richard Francis which is interlaced with field recordings of Kaka and other native birds taken at the Wellington nature reserve for endemic birdlife, Zealandia.(2)

- A replica of the ring from The Lord of the Rings made from the silver remnants of the film stock Frater had originally processed towards making a documentary film about Wellington. The ring is inscribed in Elvish with the phrase “will you carry me”. The ring circulated on opening night before being withdrawn from the show altogether.

- A trailer for the exhibition in which a human protagonist sits upon a window ledge gazing out at an unmistakably Wellington landscape only to inexplicably disappear half-way through.

Already we can see that there are all the elements of a cinematic production. There is a soundtrack, there are actors, there are production facilities. There is also an inevitable linear trajectory, in that the exhibition begins in the Kirk gallery only to traverse up the road, to look out over Te Aro valley, and to be speculatively carried away, not just with the panoramic gaze over the scenery but with the absent, circulating ring, the origin, the trace of the whole endeavour. Frater himself speaks of this trajectory as an induction into the real-time of the camera, so that the visitor also becomes an actor within the tempo of a narrative. In a similar way he speaks of his alteration to the Kirk gallery as an opening of the apparatus, so that the actors within it, the hoisted nail gun, the mortar and pestle, but also the audience, become exposed objects, printed now as functionaries within a narrative. Which is why he speaks of the separate exhibition space as the Kirk gallery’s inverse, as the projected view, both panoramic and expository, paced out by the texture of a soundtrack that is deliberately mechanical and yet entirely inductive, reflexive to life’s minutiae, something ably demonstrated by the incorporation of the field-recordings Frater cuts into Francis’ original track.

Installation view of Living Cities 2011- (2015) Richard Frater. Courtesy of the artist and the Adam Art Gallery

So there is then, enough evidence to suppose that there is more than a casual relation of Living Cities 2011- to a film, but there is nothing clinically disposed to saying why. For that we need to turn to the exhibition title’s forebear, specifically to the essay of the same name by Steve Hinchliffe and Sarah Whatmore which demonstrates how something of a city’s multiple might be better reflected in a nonrepresentational geography no longer predicated upon the idea that visible subjects must be placed inside dominant narrative orders.(3) As they suggest, what is called for is a “mapping more attentive to movement than to fixity” one that “articulates the spatialities of networking rather than of territory in the Euclidean sense."(4) We might say then that Frater similarly seeks to frame his portrait of the city in a multivalent stream, one that his initial foray into a filmic medium might have obviated, predicated as it was on a certain capturing of the specimen. Certainly Frater’s favouring of a looser grouping of actors within a framework that now mediates upon the city from multiple viewpoints echoes the non-representational project of Hinchliffe and Whatmore who focus upon the city of Birmingham through what they term an “a-critical” topography.(5) It pays here to mention that this a-critical topography is not defined by its indifference to judgment values but rather by its preference to register the fact that multiplicities reside in an overlapping fashion. As Hinchliffe and Whatmore point out, the non-foundational lens of an a-critical topography is particularly well tuned to the notion that ‘‘inhabitants are not static beings but entities entangled in a complex processes of becoming,” a reality that dictates a form of mapping that no longer seeks to identify “the real motivations of people and others,” but rather, the overlapping interstices in which a city’s multiple coheres.(6) As they suggest elsewhere, what is needed is a form of mapping in which spatialities are recognised as being “multiple rather than simply bounded.”(7)

It is at this multiplying intersection that a faithful notion of representation begins to falter, superseded as it is, by a nonrepresentational turn to the tracing of an overlapping sense of agency. This turn, as should now be more than obvious, has a direct bearing on Frater’s rejection and yet retention of the filmic medium, so that Living Cities might be interpreted both as a refusal and an embrace of the moving images’ documentary form. In this regard, Frater’s endeavour overlaps with Alan Latham and Derek McCormack’s insistence that the nonrepresentational turn necessitates a re-appropriation of the “representational veneer” that is so commonly “laid over the real materiality of urban life” in favour of a topological diagramming alert to the “processual, relational and transductive” sensibilities through which the “material ecologies of urban life can be apprehended.”(8)

It is obvious then that Living Cities 2011- overlaps with preoccupations within cultural geography, especially given Frater’s turn away from the linear entrapment of the subject in film. We can see then why he would be tempted not only to destroy his original film but to follow the process through and turn it into something else. This is an aspect pointedly picked up by Frater when speaks of the metallurgic thread that runs through Living Cities 2011-, something symbolised by the inclusion of the mortar and pestle, a device that grinds and merges one substance with another, a process that is literalised by Frater in his transformation of the film stock into a wearable ring. This metallurgic resonance is also present in the box of lead-capped roofing nails which are known to poison the embryonic food-cycle of Aotearoa’s endemic birds. Similarly then, we might say that this metallurgic affect is also evident in the nail gun, that necessary device in the transformative landscape of the pakeha occupation of Te Aro, in that the speed and precision of the nail gun significantly enables the balloon framing of suburbia’s houses to exponentially transform the landscape, a rationale that is perversely inducing the native sanctuary of Zealandia back into the landscape of Te Aro, for it stands as an artefact in need of paternalistic redemption. Such narrative circling, literally in place from the inception of Frater’s project, is no longer a simple bounding off of territories, but rather an expansion upon them, opening them up to a profusion of actors, or to use the term in which an actor undergoes figuration within a narrative, a profusion of actants.(9)

Installation view of Living Cities 2011- (2015) Richard Frater. Courtesy of the artist and the Adam Art Gallery

Actants is a much better term, for it not only identifies when an agent is in circulation but it also alludes to their role within a chain of causality. Not, I should point out, that Frater means to endlessly defer the situation, but rather, as the metallurgic trope threading through Living Cities 2011- symbolises, such circulation is instead threaded as processual, as a textuality that is multiple, that is contestable, and yet, is nonetheless an actual event. It pays also to mention this alertness to figuration does not obviate the fact that processes are uneven all the way down, nor that some factions are being used, but at least it acknowledges that reality is multiple, that there is space in this narrative not only for the dominant actors, but also those indifferent to it entirely. As Hinchliffe and Whatmore insist, cities are inhabited as much against the grain as with it,(10) a reality that necessitates a form of mapping that is openly reflective of absence as much as presence, of inaction as much as the intersection where others are acted upon. It’s precisely this refrain that Living Cities 2011- begins to expand upon. Especially given its ability to invoke the Lord of the Ring’s scenery trope, so that we might indulge in the panoramic speculation of the picturesque, only to reflect upon how much this landscape has been so actively transformed by human actors. In this sense Living Cities allows us to indulge in the melancholia made so fashionable by the hypocritical worlding of the anthropocene,(11) and yet this sense of loss, this sense of responsibility doesn’t preclude our collective responsibility for it.

But yes, what does it mean to say reality is multiple. What does it matter that we might navigate in Frater’s show an a-centric topography that extends across multiple interstices? Well, perhaps it’s easiest to begin where it starts, with the discarded film stock and Frater’s decision to turn it into a ring. What better way to signal his intent to complicate the record. How easy, as I have said, it would have been to simply invoke Jackson’s “Lord of the Rings” as a way to divert one’s attention from our own complicity in the retention of a melancholy whose thread found such easy expression in the blatant exploitation of nature as the placebo surrogate that continues to encode the anomic conditions of culture’s alienation affects. No wonder New Zealand’s marketing department has finally awaken to the illusion of this 100% lure to instead dangle the supplementary “every day a different journey,” so that even this paradigmatic window dressing might be adjudicated as provisional, even subjective.(12) So of course Frater gives the paradigmatic ring away. Lets the object circulate into an economy of indifference, as one disposition amongst many. As the ring itself reminds us, inscribed as it is with the words, “will you carry me,” there is a motivation to this economy of indifference, of one actant at work amongst many. Which as any Latourian might point out is a matter of persuasion.

If the ring circulates, the objects exposed to the narrative have a purely steadfast relation to their representation. They can’t escape. They are not just on display, but subject to scrutiny. And yet, the nail gun is positioned in a way that it reflects the onlooker, that it indicts the viewer as participant. In a similar manner the mortar and pestle drags you into its bowl. Takes you into the swirl. In fact the very real aperture of the window in the Kirk gallery compels you to take a part in this narrative. As the persuasive agent. The threader of multiples. So that one is equally complicit in this narrative of speculation. One multiple amongst many, as any city alert to multiplicities will be. Which is to say, that Frater’s rejection of the representation of film, re-finds itself in the swirl of this processual address, in which the faithful right to representation, that a capturing of the specimen, that the sampling of the demographic would entail, is ditched in order to rework and re-thread the elements of a film’s script into a multivalent storyboard that invokes the viewer to take up a position, not as mere reader, but as an embroiled actor, an actant taken up by the figuration of a story that is multiple.

Installation view of Living Cities 2011- (2015) Richard Frater. Courtesy of the artist and the Adam Art Gallery

Elsewhere Hinchliffe has written of the city as a multiple, so that one might experience a bifurcation of the city, of its folding into one city amongst many. (xiii) In a relatively succinct example, Hinchliffe works this brief through the example of a community garden, examining it from the point of view of non-governmental-organisations, civic functionaries, religious leaders, and actual gardeners. To this we might also add the leisure strollers, the iterant animal populations, the bees, the dogs, the foxes, but also the plants themselves. Sure geographers might notate the composite soil levels, urban regeneration might encourage iterant plant communities to congregate, but we would find it difficult to really experience the city from the point of view of soil. Maybe, but the point Hinchliffe makes is that we need not reduce this multiplying aspect of the city, but rather that its precisely in this relation, in this multiplicity that gets more complicated the more we understand it, that notions of movement and prehensile articulation actually come to have meaning. To relay it back to Frater’s representation of Te Aro as an interstice of multiple actors, what we experience is a viscous mesh, a network of persuasion that is as tangible as it is speculative. It is precisely here that we experience the multiple of a living city, not just the writing of it, but the actual, alert, mobile reality, an aspect perfectly reinforced by the Living Cities 2011- trailer, in which the human protagonist inexplicable disappears half way through, not because her absence makes the work more poignant but because the city goes on regardless.