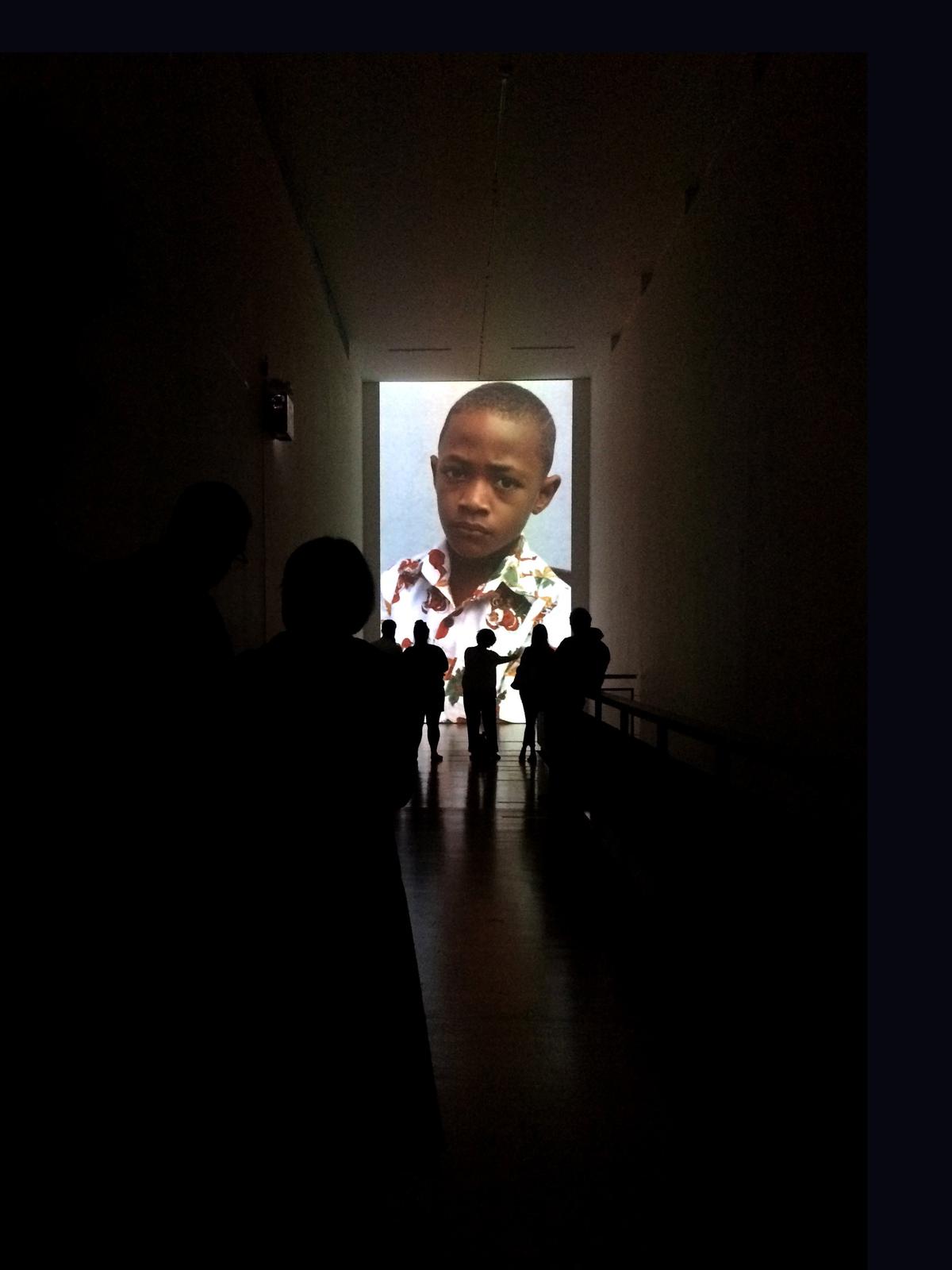

There’s only one new work here. How Long? (2018).(1) Filmed in Fiji, it is a series of four portraits which takes as its subject the global deployment of Fijian soldiers and security forces over the past four decades. Each is filmed in Thompson’s, by now familiar, customisation of Warhol’s screen tests, albeit this time in colour, but still silent and still casually interrogative, the subject prone before the camera. And yet, unlike previously, there’s no steady emotive subject here. The subjects are in equal parts inquisitive, bored, resentful, excited but not entirely focused.(2)

This complexity of response differentiates How Long from the other films on display. That is, autoportrait (2017), Thompson’s sister image of Diamond Reynolds, filmed as counterpart to her Facebook broadcast following the death of her partner during a routine traffic stop by Minnesota police, and the older, Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries (2016) which comprises two portraits of descendants of similar systemic violence perpetuated against black lives in London. In both of those works the portraits are punctured by their immediate context, their historiography if you will. I will return to this point later, for there is a latency to these representations that is worth exploring. However, what is immediately obvious, and it is plain to see in the doubling up of How Long with autoportrait in the two adjoining galleries, so that if you move to the side of that gallery you can watch the two films, stacked upon each other (autoportrait in the lower gallery playing building block for How Long in the top floor gallery) is how different the interrogating-interrogative subject is represented. To be specific, in How Long the subject is less focused, more wary of the camera, caught between moments of pride and suspicion, whereas in autoportrait the subject is composed, purposively performative, you might even say, in control of the camera.

How Long’s subjects are, after Fijian custom, all named after the war zone where one of their parents either served or was killed. So we meet (in anglicised form), Jone Lebanon, Rosi Lebanon, Rupeni Iraq and Inia Sinai, sketching purportedly an “embodied timeline” of the deployment of Fijian security forces in the West’s conflict zones. Perhaps though we can turn to the interrogative prolix of the title (how long) to suggest something more obvious, that is, we are met with the indifference and scepticism of a populace that is continually displaced if not disrupted through their mercenary deployment in another’s war. Reading the title as such certainly makes sense of the complexity of emotions captured in the subjects performance, so that as much as this is yet another voyeuristic encounter with the abject historiography of trauma Thompson has commodified, we meet instead a nuanced portrait in which the subject is alert to their representation, whether that’s the stoic reflection of Jone Lebanon, or the timid awareness of Rupeni Iraq, not to mention the deflected readings of Inia Sinai’s carer, who cradles the baby with maternal pride and yet scepticism towards the voyeuristic camera, the camera that would both freeze and commemorate the subject. For it is not fair to simply say that How Long points to the extractive vices of a colonial-capitalism that would use human resources as mercilessly as it has mineral deposits, without considering the agency of those who serve. Which is why the portraits oscillate between pride and scepticism, moving through an emotional range that is absent from Thompson’s other portraits.

Luke Willis Thompson, autoportrait (2017) 35mm, b&w, silent, 8 minutes, 50 seconds @ 24 fps, 35mm Kodak Eastman Double-X BW. Installation view at Adam Art Gallery, Victoria University of Wellington, 2018. Photo: Shaun Waugh.

There is very little to say about Diamond Reynolds’ portrait that hasn’t already been said.(3) Surely we are bored to death by her story, so much so that we turn instead on the exposed subject, wondering at her thickly applied make up, her lewd jewellery, her entrepreneurial status, her silent mutterings as girlish sing song.(4) We debase the subject we become over familiar with, particularly given the context of our emotional connection to the grief of her Facebook feed. In that film, in its blunt political reality that upholds that genre of indignation, do we not enjoy an emotive flight of fancy in which we share, if not momentarily indulge, in the historiography of colonialism’s proximity to its extractable commodities. Do we not simply pretend to connect the systemic protraction and perpetuation of our shared inheritance of a colonial-capitalist nightmare we can’t wake from? Should we be surprised then that Thompson might want to make a sister image, not so much a corrective as it is an image that outpaces that initial connection the Facebook video’s indignation presupposes. No wonder then that the film is pitched as collaborative, as Reynolds’ being in control of the image, of a composed thoughtful rendition. This isn’t so much the voyeuristic encounter with trauma the more it is a direct mediation on the perpetuation of the systemic oppression of one race as the exploitable precondition of another’s success. Such then is the solemnity of Reynolds’ mood, not just the grief of the survivor but as the used and passed over spectacle of the triage of colonial-capitalism’s cyclic exposure of its proximity to its victims, as the necessary, concomitant device of its own success.

If the previous reading seems overstretched its worth recalling here that Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries, the portraits Thompson made of Brandon, grandson of Dorothy Groce who was shot by police in her home in Brixton in 1985 and Graeme, the son of Joy Gardner who was the murdered in her home in botched police raid in Crouch End in 1993, is titled after the figurative device in Duchamp’s Large Glass (1915–1923)(5), the mobile of men’s uniforms, that dangles below the bride. Considered by Duchamp as the “nine external containers”, these “uniforms or liveries”(6) are the futile bachelor machine’s transportable mobile, proffering a range of predetermined occupational roles that the ascending subject might take up. Indeed, posed in this context we might think of these moulds as reflecting Bourdieu’s habitus, that peculiar mixture of class, education, and socio-economic matrix that determines one’s ability to navigate the proclivities of anthropoid life. Read this way, we can certainly see an overlap with Thompson’s earlier work, inthisholeonthisislandwhereiam, (2012), which posed the empty gallery against the over-inhabited house replete with the furnishings of a particular habitus. Indeed the pessimism of that title, which transcribes a kind of levelling up to the trajectory of life, echoes the schedule of Duchamp’s Large Glass, its' conscription of the male’s vocational choice into a kind of futile habitus, which grinds out the desiring male according to the trite role-play of phallogocentrism’s most dominating traits.

Luke Willis Thompson, Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries (2016) 16mm, b&w, silent, 9 minutes, 10 seconds @16 fps, Kodak Tri-X 16mm b&w reversal stock. Installation view at Adam Art Gallery, Victoria University of Wellington, 2018. Photo: Shaun Waugh.

Given this overlap it’s worth exploring what exactly the moulds of Graeme and Brandon’s portraits presuppose. I mean are we simply to extrapolate that such roles, the nine uniforms, are simply unavailable to black lives, something reflected in Thompson’s purposeful use of Kodak Tri-X film stock, not just because it was Warhol’s film of choice, but because “Tri-X was never metered for non-white skin tones”.(7) Perhaps, but then that leaves the rather pessimistic reading that black lives are simply preconditioned to take up the role of the victim, which given the staggering systemic violence perpetuated against them is meaningless in the extreme. Rather, perhaps instead we might heed the Manichean representation of the portraits themselves, particularly in the obscuring of one of the portrait’s visage which is half in light and half in shade.(8) Such representation doesn’t just recall Frantz Fanon’s depiction of the colonial apparatus(9), but also hints at the kind of subaltern agency colonialism has always been supplemented by, allowing a kind of withdrawn subjectivity, a habitus of its own making. In this instance then we might look to Thompson’s nomenclature as a type of moulding in itself, creating what he calls "a kind of counter-image", "a portrait against that history"(10), transfiguring the uniforms, the liveries Duchamp’s phallogocentric narrative ought to have finished with.

The habitus then is clearly a way into Thompson’s work, one that not only makes sense of the types of cladding Diamond Reynolds is embroiled in, but one that allows a kind of agency for the subjects of these portraits that goes beyond the desires of the audiences who encounter them.(11) Thompson has in fact been blunt about such agency chiding the preoccupations of readers who transpose their own habitus into all too specific readings.(12) Nowhere is such baiting more obvious than in his use of Reynolds’ singing in autoportrait which is, as he suggests, not just “visually difficult to decipher” but “designed so that the audience has the opportunity to mentally interpolate whatever they need or want to hear”.(13) Such locutions transpose competing habitus, exposing not just the subject on display but the preconditions of our own reading, something that underwrites the subjects on display in How Long. How then are we to read the consciousness of Jone Lebanon, his stoic posture, his decision to face the camera in profile, to look not at us, the viewer, but deliberately off screen? And yet this isn’t the profile of indifference but perhaps thought itself, memory materialised, hard at work labouring over the eclipse of time between one event and the habitus Lebanon is now immersed in. We might similarly see the rest of the portraits in the same vein, never so much belying the momentary appearance of representation as a commemoration that traps and isolates the subject, but as a trajectory, a vector, upon which the habitus arranges itself. Perhaps this then is how we might think of Thompson’s interrogative title (how long?), not simply as the indignant wail of our confrontation with the structural indecency of global capitalism (how long!), but rather, as the indictment of our own habitus’ duration (how long?), reflecting in turn its formation, its limitations, and in part its own redundancy in an age predicated on an apparatus that simply refuses to pause.