I climb up the concrete stairs in Masons Lane and end up in front of a screen that’s tucked into a dark corner, encased by a protective layer of glass. Although this lane is new for me, it’s on a regular route for many other people. It’s lunchtime, and a steady flow of pedestrians surrounds me. Pausing before the screen to gaze at the videos, I get a few odd looks from passers-by. It feels subversive, to stop moving and just watch.

Masons Screen is located on a pedestrian walkway between The Terrace and Lambton Quay, and is run by CIRCUIT, who have been commissioning and exhibiting moving image works from established and emerging artists since 2016. The list of past contributors is impressive, as are the artists who’ve created the four commissions for the 2022-23 programme—Xi Li, Matthew Cowan and Jana Müller, Leala Faleseuga, and Hana Pera Aoake. Each artist demonstrates a considered approach to the site’s relationship with place, each film interrogating the viewer’s interaction with its urban setting in distinct ways.

Xi Li, Prosperity or Emptiness (2022)

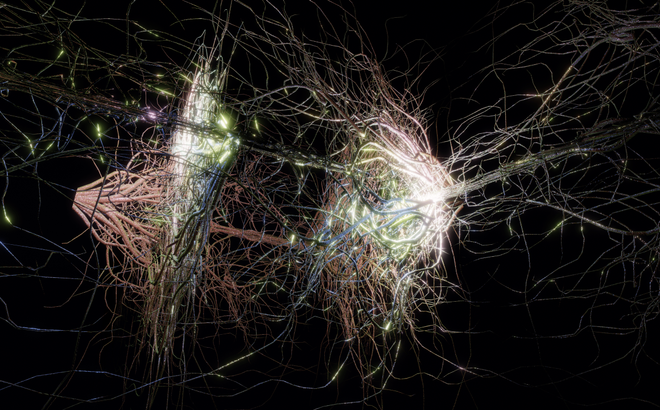

The season’s first commission, Prosperity or Emptiness (2022) by the Chinese-born, Tāmaki Makaurau-based artist Xi Li is a work that uses abstract and fragmented 3D visual animations to create “an experience and metaphor of urban life.”(1) In its opening scenes, the video immerses the viewer in a kind of limbo space, a deep dark cosmic world where spindly webs of hair-like wires encase and connect a series of glowing figures—a head, a tower structure, a sun, and other indistinguishable silhouettes. These objects rotate on their own internal axes as if each is its own planet—spinning in time, isolated from one another. But while they are separate, they exist in a forest of wires that glow with energy and connect each object to the other.

This network of wires appears to mimic the invisible signals and structures that tether us together in the digital age—while also mirroring the electrical wires and fibre-optic cables that run beneath our feet, becoming the veins that are vital to the life of a city. Standing before the work, I imagine myself as a glowing figure in a vast space, connected to the people around me as if by a radiant web. I imagine the city’s tendrils reaching below and above, electricity streaming, powering trade and transmission alike.

Still from Xi Li, Prosperity or Emptiness (2022)

In the next scene, the video pans down to a monochromatic and unpeopled landscape. In this world, there’s no life or movement, only remnants of humankind. An oversized head is half-buried in the ground, the body is reduced to a relic. A large, abandoned castle towers over this apocalyptic scene, which is dotted with unfinished structures—staircases leading to nowhere, lone barbed-wire fences, and archways overgrown with vines. These structures become absurd monuments to the fragmented digital realms we exist in and the contemporary cityscapes we inhabit. Recalling the pyramids and pantheons of past civilisations, the looming castle acts as a dystopian memorial to humanity.

The work’s title, Prosperity or Emptiness, prompts reflection on a contemporary paradox: whether our technologically optimised society is, in fact, providing us with greater prosperity and satisfaction—or, as Li asks, whether having unlimited access to information and the potential for connection actually causes the opposite—increasing isolation and dissatisfaction. The work repeatedly calls into question the notion of technological progress, and in so doing prompts other questions: Is constant connection to the internet improving our lives, or does it leave us feeling empty? Do our urban landscapes encourage or discourage us to interact with and relate to one another? Is the prosperity of a few really helping the planet, or is it destroying us?

Jana Müller and Matthew Cowan, Background Scenes (2023)

Next up, Background Scenes (2023) is a collaboration between Jana Müller and Matthew Cowan that addresses the complexities of authentic representation. The pair have worked together since 2021, aligning their respective interests in the role that museums and archives have in representing identity and history. Extending from their research into the painted backgrounds used in 19th century photographic studios in Europe and New Zealand, Background Scenes explores the potential of moving image as both document and performance, bringing lens-based and painterly modes of representation into conversation with each other. In this work, large-scale, sublime landscapes are painted onto swathes of fabric that are then hung and filmed in front of real-world backgrounds—tropical palm trees lie on a rural railway while trucks drive past; a scene of picturesque mountains sits amidst harakeke bushes; the waves of an ocean beach extend into a misty, grey river. As the artists note,

In this way there are two levels of reality exposed, addressing on two levels Barthes’s claim that "realism (badly named, at any rate often badly interpreted) consists not in copying the real but in copying a (depicted) copy of the real." Realism is not necessarily an antonym of fiction.

The picturesque landscape paintings reference the fabric backdrops used by early colonial portrait photographers to create an illusion of belonging for their clients. In these paintings, there is an element of fantasy and escapism—along with the promise of a sublime ‘elsewhere’ which the colonies were meant to embody. These backdrops echo the work of early colonial painters, such as William Hodges, who aestheticised and romanticised the New Zealand landscape, representing it as unpeopled and ‘ripe for the taking’.

Cowan and Müller have deliberately juxtaposed these landscapes with real world contemporary settings that are prosaic and mundane, in order to highlight the disjunction between representation and reality. The real world settings could represent any place—the in-between spaces we take for granted. Through the work’s series of contrasts and layering of realities, even the most banal background is re-framed as art—letting us see the backgrounds in our lives with new eyes.

Still from Jana Müller and Matthew Cowan, Background Scenes (2023)

They continue, “This fantasy of portraying one world in another is still in use today, in myriad of digital realms. Whether painted or digital, backgrounds don’t promise authenticity of location, but authenticity of affect. Our work seeks to transgress in the space of this authenticity allowing the layers of fiction and reality to reveal themselves.”(3)

The modern fantasy that they speak about here is one that is familiar to most of us. We are increasingly aware of the levels of fiction that come with representing any background scene. In an age of social media—of AI filters, deep fakes, and where influencers fabricate attendance at events like Coachella—issues of authenticity are becoming increasingly fraught. What Cowan and Müller have created is an interplay of different modes of representation that call reality itself into question.

Leala Faleseuga, Vessel: Dissolution | It's in the milk (2023)

This work is followed by Leala Faleseuga’s Vessel: Dissolution | It’s in the milk (2023), a deeply personal work born out of the artist’s own experience of giving birth to premature twins and the resulting prolonged stay in the hospital. In the film, photographs of Faleseuga at different stages of her pregnancy and pictures of her children shimmer in pools of developing fluid and milk. The images flicker and shift as a voiceover muses on the memories they evoke:

Some images shimmer, double-exposure magic between worlds, slow shutter speed softness, light trapped into form, chemical smears on the edges of the frame, squares of everything—light in my palm. I flip through the photos…

Faleseuga’s voiceover is gentle and poetic. In it she speaks to her visceral experience of motherhood, building an additional layer of documentation to that created in the photographs. By their very nature, photographs represent a strange relationship with time—they freeze split-seconds into permanent images, stilling moments which would otherwise pass us by. A photograph is an artefact through which we can revisit and re-encounter the past, over and over again. It is a memory device whose meaning continues to evolve over time—just as memories themselves do. To take or even to interact with photographs is an act of time travel.

“I always love photos for their memory recall properties...” Faleseuga says in an interview about her work, “the way you remember something very much shifts with time...”(5)

Still from Leala Faleseuga, Vessel: Dissolution | It’s in the Milk (2023)

Of the site itself, the artist reflects on the setting of Masons Lane, and how her intention to exhibit fragments of deeply personal, private moments in public spaces is intentional. She says: “The content itself is about intimacy, it’s about birth, it’s about motherhood, it’s about grief, and I thought it was very intimate and it would be quite a nice contrast to the space itself. And I thought that if people only caught a snippet of any of it, that’s actually true to the whole… project.”(6)

I can see what she means. Pedestrians spend only a few moments here, always passing through. The lane is a transient space, a passage to get to somewhere else. My visit is intentional, but I find myself wondering how others encounter these works—do they even notice? Do they stop to look? How are we to lift our eyes from ourselves (or our phones) to truly engage with the people around us?

Hana Pera Aoake, I saw the mountain erupt (2023)

The most recent commission is Hana Pera Aoake’s I saw the mountain erupt (2023). The work takes as its point of departure Morgan Godfery’s personal essay I saw the mountain erupt: a Kawerau childhood to tell a geological history of Kawerau, which at the time of Godfery’s writing was New Zealand’s poorest town. In Aoake’s work, footage of billowing factory smoke and industrial wasteland is contrasted with scenes of trees, rural landscape, and deep water. These visual fragments are interspersed with lines from Godfery’s text, distancing the words’ meaning from the original memoir to something more poetic and indeterminate.

The work calls on manu (birds) and tuna (eel) to bring forgotten pre-colonial Māori histories into the present. The eruption of Mt Tarawera in 1886 destroyed the area’s Pink and White Terraces, known by Māori as Otukapuarangi and Te Tarata. It also led Māori who had traditionally lived in that area to leave. In Godfery’s words, “Māori villages evacuated after thick, black ash from the Tarawera eruption poisoned the soil in 1886.”(7) The implication is, of course, that it was not only natural forces that poisoned the soil. In these lines we see foreshadowed the stratification of violence and brutality that permeates this land.

Still from Hana Pera Aoake, I saw the mountain erupt (2023)

A powerful act of revisioning, I saw the mountain erupt encourages viewers to be attentive to Māori histories and relationships to whenua, maunga, and awa that long pre-date the construction of our cities. This feels like a particularly important message in the heart of Wellington—where many decisions that impact Māori land and people are made. I find myself hoping that the work will stop people in its tracks.

So I stand in front of the screen and watch the video over and over. Most people walk past, they have places to be. As I stand there, one woman looks up at me with gentle curiosity as she climbs the stairs—most likely she’s wondering what’s caught my attention—and takes an interest. She pauses beside me. We stand and watch together. This feels special, to connect with a stranger over art in a public space. And even though we don’t speak, for a moment, in the midst of the hectic energy of the city, we are both transported to a different world.

Hana Pera Aoake’s I saw the mountain erupt is playing at Masons Screen until 19 June.

Sinead Overbye (Te Whānau a Kai, Ngāti Porou) is a researcher, historian, writer, and editor who lives in Wellington. Her work has been widely published, and she is currently the Kaupapa Māori Editor at the Pantograph Punch.