The history of art is primarily known through photography, and perhaps no more so than in New Zealand, with it's European history, and yet it's absolute geographical distance from what we traditionally perceive to be the cutting edge of contemporary art practice and exhibition.

Media Art is the perfect type of work to bridge the geographic divide. Often dematerialised, yet highly reproducible, the work is easily transferred across distance with less of the financial costs associated with say, moving a large sculpture or painting.

In terms of film and video this practice of moving the work around might be called Distribution. Distribution of exhibition prints. Distribution of rental prints. Distribution of preview copies for prospective shows. Distribution of library copies that provide opportunities for entertainment, education, study, research.

Between the sending of the print and the return of the print (if returned) exists that period of opportunity for copying. And from that we have what Hito Steyerl has termed the poor image.

The poor image is the 2nd, 3rd or 10th generation copy that often bears the grubby technological fingerprints of repeated dubbing and occasional technological malfunction or interference.

Distributed amongst underground networks of shops, stalls and latterly websites, these poor copies are celebrated in private by enthusiastic individuals or at social get-togethers of similar souls with a shared passion for the work. In this context the quality of the first encounter with the image is irrelevant, the enthusiast just wants to see it, to get a sense of it, to sniff out its capacity for revelation.

I trace my own introduction to avant-garde moving image practice not through attendance at art galleries, but via these underground channels of distribution; watching hopelessly degraded VHS transfers of Richard Kern's late '70s 8mm films from the Cinema of Transgression; watching Survival Research Laboratories video documentation of staged mechanical warfare through a fog of VHS wow, flutter and drop out.

Still from A Plan for Social Improvement, Survival Research Laboratories (1988). Sourced from Ubuweb.com

While the aforementioned underground networks have their own dealer/collector mentalities and protocols for exchange, let's bring the conversation back to the public and dealer gallery.

For the collector or collecting institution, this distribution of the poor image can provoke some anxiety about the authenticity of their copy of the work. "Where is the exclusivity? Where is the aura?" Why should I buy this if there are 25 more copies floating around on DVD? Why should I buy this if it's available to view on www.circuit.org.nz?

Well, let's have a look at the CIRCUIT website. I'm going to show you Aerial Farm, the Phil Dadson work now showing in the Adam Gallery. All of the videos on CIRCUIT come from the artist.

Screen grab from www.circuit.org.nz, showing Aerial Farm (Polar Projects) (2004) Philip Dadson

The version of Aerial Farm you see on CIRCUIT is a heavily compressed image, generated from a larger file, and prepared for fast streaming on an internet browser.

By contrast, when I look at this work in the gallery downstairs (which comes from a much less compressed file) I see an image that seems to hover, to drift in and out of sculptural relief. When I look at this work on the CIRCUIT website the image is flat.

Now let's talk about our encounter with the work. Downstairs the image is large and immersive. We sense human vulnerability within the harsh Antarctic climate. When I watch Aerial Farm on www.circuit.org.nz I see it on a 12” Macbook Pro screen, and none of this vulnerability comes through.

Let's talk about sound. When I listen to this work on www.circuit.org.nz I hear the sound from my two tiny macbook speakers. When I listen to this work in the Adam Gallery I hear the sonic whip of the wind curl around my ears.

I make this comparison to illustrate one of the important issues at stake here: What exactly constitutes the work?

The question is not just limited to media art, the moving image or whatever. I'll never forget the first time I saw a Mondrian painting in the flesh, so to speak. This was not the textbook image I had studied at school. The lines at the edge of the blocks of colour were not straight but wobbly. Instead of laying flat the surface of the canvas, the paint was layered, heavy and undulating. It had materiality. I saw the painters hand. When I see Aerial Farm downstairs, I see if not the painters hand, then the videographers eye.

So how does representation on CIRCUIT—or the distribution of the poor image on CIRCUIT support the collection of media art? All of the work on the website comes from the artists themselves. Since streaming their work on CIRCUIT, several artists have reported that they been offered gallery-based shows for their work nationally and in one case, internationally. The resulting opportunities have generated sales, exhibition fees and exposure for their work.

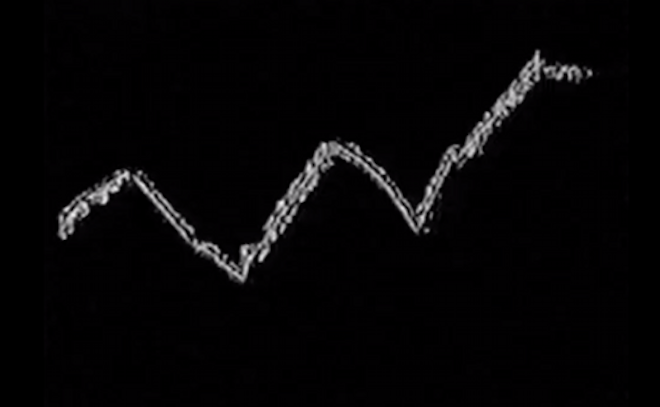

Outside of CIRCUIT perhaps the most classic local example of how the distribution of the poor image supports the distribution of the artwork is Len Lye; after poor digital transfers of his work began appearing on YouTube, the Len Lye Foundation experienced a sharp spike in interest in rentals of the 16mm film prints, whose sense of physicality I have yet to see represented in a digital copy. Certainly not on YouTube.

Still from Free Radicals (1957) Len Lye. Source: YouTube.com

With both cases, it is clear that the distribution of the poor image supported and directly led to the distribution of the artwork.

My digression into my late-night encounters with the poor image comes from a pre-You Tube era. Today all of the material my restless young mind could ever have wanted is more or less available to watch online. The largest resource for this is Ubuweb.com, a massive sprawling collection of poor images from the world of documentary, video art and elsewhere which numbers in the thousands. Everything I could ever have wanted is there; yet faced with all the candy in the world, I feel defeated. Where to even start? Last time I checked in with Ubuweb I went browsing and for some reason ended up watching video documentation of Henry Miller having dinner.

Here I come back to the importance of the institutional gallery, which brings curatorship, context and critical thinking. The gallery collects work of note, which it chooses to exhibit in a future context that resonates with the present moment, cutting through the fog of poor image abundance and staging a potent encounter between the work and the viewer.

Until that moment, I hope the poor image continues to light a fire of enthusiasm under the viewer that might, in future years lead them to a more fuller encounter with the work, as I hope the comparative viewings of Aerial Farm on CIRCUIT.org.nz and here at the Adam will do.