Form Next to Form Next to Form is a publication by film maker Nova Paul, which celebrates and re-presents her 16mm film This is not Dying from 2010. Turning a film into a book is an interesting proposition, but rather than explanations and stills, Form Next to Form Next to Form translates the hallucinatory language of the film into the print medium, creating a work that casts its own spell.

This is not Dying is a portrait of Paul’s ancestral homeland under Whatitiri Mountain, near Whangarei. This cluster of houses is the site of simple communal living, with shared meals, card games, mokopuna changing hands, young men tinkering with motorbikes, and kids bathing in the Wairua River. Paul unravels documentary norms by prising apart time and space, allowing a zone for new forms to coalesce, new forms of seeing and being.

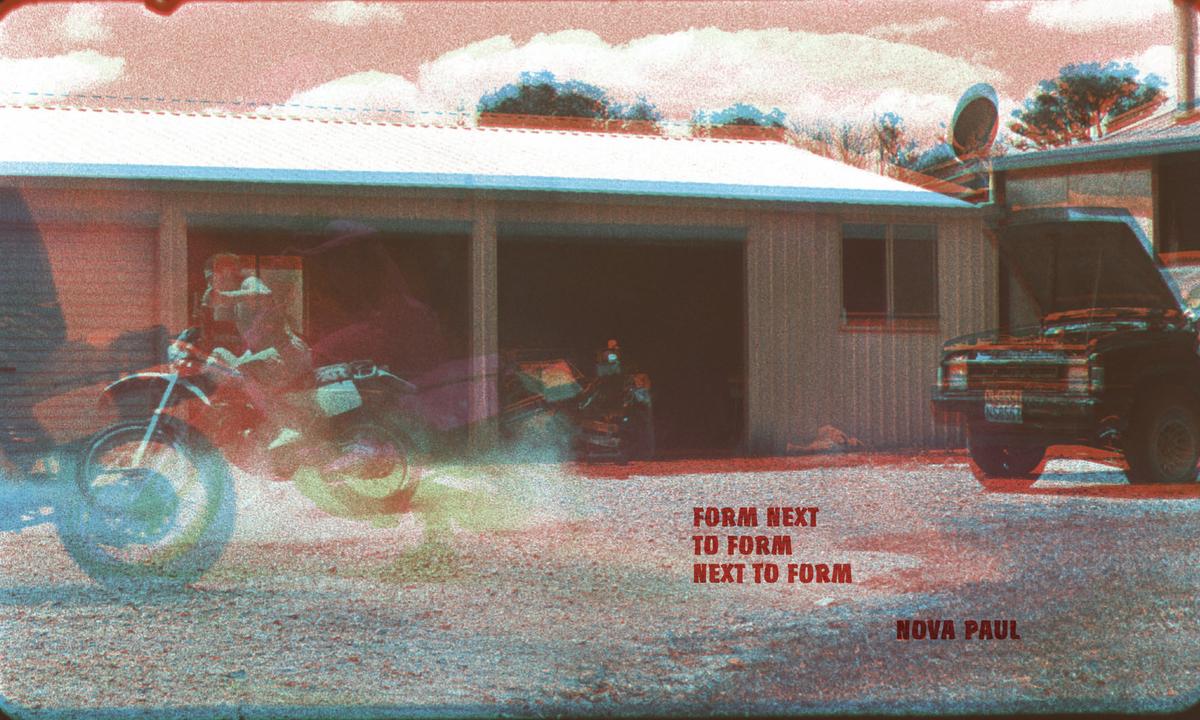

Still from Form Next to Form Next to Form (2013) Nova Paul

Simply put, Paul shoots the same scene three times, and each shoot is colour graded red, blue or green. The three strands of film are then woven together with all their glorious misregistrations as a moving, morphing, technicolour evocation of life in the present moment; a present which is layered-up with past and future in a cosmic, pregnant unity. It’s a process Paul acknowledges has its genesis with the experimental films of Arthur and Corrine Cantrill, and she has used this method before, in Pink and White Terraces (2008). But while the achingly beautiful Terraces recorded random snatches of life around Auckland, This is not Dying is a dedicated love song to a specific site and way of life.

And speaking of songs, the endless summer of the north is serenaded by the late Ben Tawhiti, a showband kaumatua with 60 years of playing experience, layering multiple guitar tracks including steel guitar which wafts like a breeze both warm and mournful, through the jewel-like textures of the film. Tawhiti chose to play the Ngapuhi anthem, “Whakarongo Mai,” in tribute to Paul’s hapu, and the book features a vinyl single in its own cardboard sleeve, tucked into the back cover, so you can listen to Tawhiti’s magic while you flick through the pages.

Form Next to Form Next to Form uses the same colour-separation logic as the film. Rather than reproducing coloured stills as they appear in the film, Paul supplied her designers (Abake) and publishers (Dent-de-Leone, London) with black and white images which were each colour-graded in red, green or blue and then collated to create the same chromatic blow-out effect as the film, only here it’s for the printed page. The two media treat colour differently, because the film uses additive colour (light), while the printed page uses subtractive colour (pigment); the film yielding “turquoise, pink, lilac, apricot, mixing into a palette of purple, lemon, crimson,” the book mixing up darker purples, jades, and peacock shades, against a high-key sherbety scarlet. The book pushes the medium even further than the film – mixing and matching three-colour superimpositions with images that are just blue, just red, or just green, and leaving evidence of process, such as the rounded edges of the lense, visible at the corners of the page.

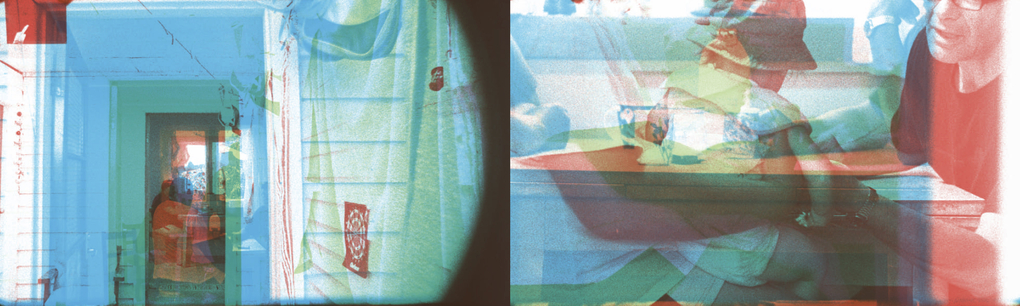

Still from Form Next to Form Next to Form (2013) Nova Paul

Paul and Gwynneth Porter have collaborated on an essay, The Virtues of Trees, which meanders between the book’s images like the Wairua wraps itself around rocks, creating rainbow sprays of thought by turns mystical, political and philosophical. Much of the discussion centres on notions of time, which in Paul’s film “has a different texture, more embodied than measured.” In keeping with unmeasured time, the book is unpaginated, and the co-written essay slips between two subjectivities – sometimes the first person belongs to Paul, sometimes to Porter, (I & I), and sometimes they coalesce into a “we.” Wairua means literally “two streams,” and all of Paul’s oeuvre represents convergence, collaboration, cooperation. Indeed, the film, its soundtrack, the book and the essay are all composed of subtly intertwining layers, which, according to Paul and Porter, creates a “floating world, one where ancestors walk about with the living...” On watching the film, one of the local kids comments that the coloured echoes of figures peopling the frame “look like ghosts but they aren’t scary.”

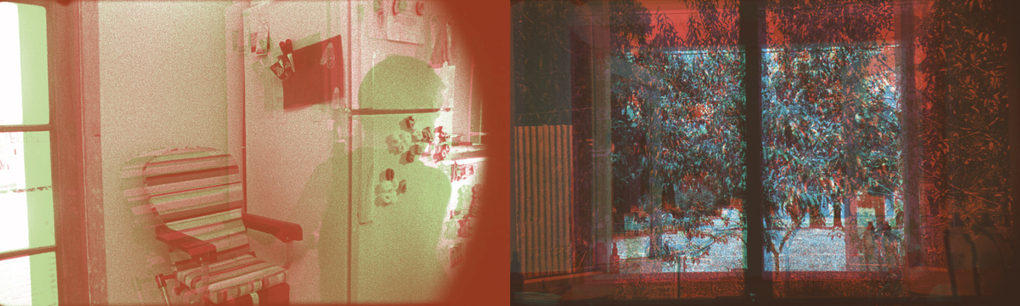

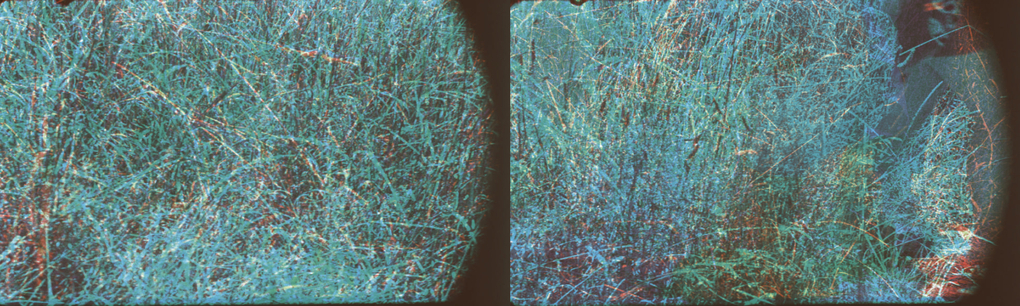

If perambulating people become colour-separated ghosts, then trees, which bear the names of ancestors, become shimmering demigods. They are alive with mauri, performing a movement which the essay likens to “wiri” or the “trembling of hands” in traditional dance. Even in the still format of the book, a peach tree seen through a window seems to dance, its boughs ribboning leaves in peacock, jade, amethyst and ruby. There is a double-page spread of tangled, overgrown grass, wild and glittering, while watercress growing out of the river morphs into the heke, or ribs, of plants, fish, houses, people, or the clouds in a mackerel sunset. A marbled leg languishes beside the gushing river. Like rainbow oil slicks on tarseal, Paul has captured moments of magic in the everyday by literally adjusting the lens we use to perceive the world.

Still from Form Next to Form Next to Form (2013) Nova Paul

There is a moment during the film when one of the kids reaches into the freezer for an ice-block, and the camera pans past some educational fridge magnets which spell out “Maui Catches the Sun.” This is the crux of the film—its defiant ability to slow down time—to capture fleeting light in all its nuances, not by accelerating to light speed, but by slowing light down to humanly-compatible wave lengths. In part, this is achieved by making “the camera a listener,” following the sage advice of filmmaker kaumatua the late Barry Barclay.

The film’s title is of course lifted from the Beatles’ classic Tomorrow Never Knows, recorded at the dawning of the psychedelic era, and featuring the exhortation to “Turn off your mind relax and float downstream.” But This is not Dying speaks to a wider set of issues than young white kids getting high. In 1856, New Zealand politician Dr. I. E. Featherson expressed the then typical colonial position that Māori were doomed to die out, and that “Our plain duty, as good, compassionate colonists, is to smooth down their dying pillow.” Paul’s disavowal of death, then, is a wero, or challenge, to colonial arrogance and ignorance. As much political as psychedelic, Paul’s northern love song portrays a site of cultural resistance, as well as a blueprint for better ways of living. For all of us.

Form Next to Form Next to Form can be ordered online through Clouds Publishing here.