Imagine, we are stopped in our tracks by a stunning work of Art, so powerful or perhaps sublime it remains imprinted in our brain forever. The image like a meme tune comes back to us unexpectedly in our thoughts from time to time for no conscious reason. Perplexingly, we don’t necessarily recall the title of the work, the artist or when it was made. Intrigued by Ngāpuhi artist Nova Paul's stated interest in the "self-determined" image, my opening words are personal thoughts of what she might mean. I am suggesting that this hypothetical work of art sits purely in the mind of the viewer, existing outside of a real place; an ‘other’ place perhaps.

Surplus Reality is the name of Paul has given to the work that I am looking at. It could be seen to be paradoxical to name something that the artist wishes to be "self- determined" suggesting that "this" thing means, or is, ‘that’ thing. This conundrum is however, a starting point for a deeper discussion. The title could instead, refer to the place and time of the show and the journey taken through the spaces. The title then refers to us, the viewer and not the work.

My initial reaction to seeing Paul’s work was to recall The Treachery of Images (1928-9) by Rene Magritte and the subsequent writing by Michel Foucault titled This is not a Pipe (1981). Even as I write these words, I am framing the argument in this dominant hegemonic language, perhaps the very root of the problem where literally, English has "the final word."

Paul’s artist statement relates the title Surplus Reality to the practice of psychodrama implemented in Queen Mary Hospital in Hanmer Springs between by the superintendent Dr Robert Crawford 1976-1991. Patients recovering in the addiction program are asked in therapy sessions to imagine a "Surplus Reality" and new possibilities where they are "freed from the constraints of their everyday reality". Self-medication then, is often our choice to use alcohol or painkillers to heal perhaps the self-doubt and despair that seems to weigh down our lives. We just want to be happy. We seek to escape from the oppressive domination of a hegemonic Western narrative encompassing Law, Religion, Society, Morals and Ethics telling us who we are, what we should do and expect from our lives. If we medicated our way into a state whereby we have poisoned ourselves, might it also be possible to self-diagnose our way out? Through a "surplus reality" could we create our own personal narrative intrinsically based on how we see the world? A utopia for one, perhaps?

Intuition vs Institution

In the Hegelian tradition, Paul uses art and history to create her own narrative. Her whakapapa remains a salient theme in much of her work, particularly her major 2010 film, This is not Dying. The work functions as a cinematic mihi, where the audience is introduced to both her unique film practice, her Māori identity, her Iwi (Maungārongo) and her mountain (Mt Whatitriri). For a New Zealand artist, it perhaps echoes the McCahon cry “I Am”: a shout, a call for autonomy, a simple self-signification of who we are in what seems to be an over signified world. "I AM" as distinct from to the fascist finger pointing, "YOU ARE".

Apart from the aural karanga/welcome, Surplus Reality has many more oblique references to this earlier work. The disembodied voice is not synced with the two films and the speakers are not placed beside the images to so that our ears and eyes might be orientated in the same direction. This causes the first of many discombobulations occurs as the viewer becomes confused, trying to make sense of the first of the two rooms in the Physics Room gallery space. The cold winter sun struggles through heavily darkened windows in this otherwise empty space while the wall opposite the windows is filled with two scenes that gently alternate in a continual loop. Every one to two minutes the scene changes from what seems like dust or dirt blown or thrown through a shaft of light in a dark sky to a striking image of what appears to look like a stark mountain. Perhaps this is a representation of Mt Whatitriri, however suddenly I’m thinking “This is not a mountain”. Once again, I am disoriented as I come to the realization that I am looking at a pile of dirt. I am never the less beguiled by the beauty of this "model" mountain, filmed from the ground to appear dominant and majestic.

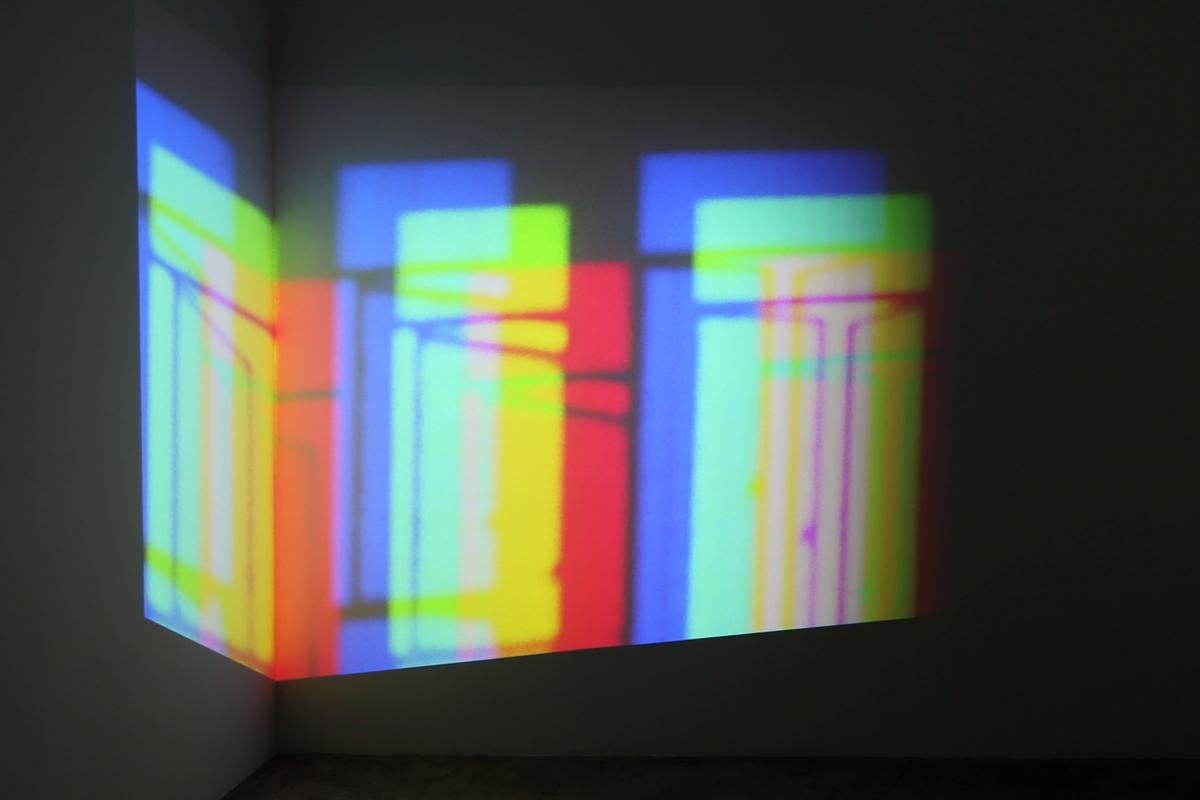

Installation view of Surplus Reality (2017) Nova Paul, The Physics Room (2017

Something else is going on here. This is not a mountain or This is not a Pipe leads us back to Foucault as he questions Merleau-Ponty’s ideas on the primacy of perception as a single, shared response to the world around us. Does everything have a single primary essence that it refers to, or are they just "similar" to many "other" things? Magritte’s painting has multiple pipes. Neither are useful for smoking, yet they remain "Pipes".

Written language has long been the basis of western knowledge, laws and Religion. i.e. “In the beginning was the word”. Already a century ago, early modernist artists sought to distance language through abstraction in art. They had utopian aims in developing and inviting the viewer into a single shared spiritual (no) "place". Importantly, their hope for a collective understanding declines at the same time as fascism in Europe in the 1920-30’s is rising. Nazism revealed perhaps the true face of utopia; a single collective narrative, with total disregard for the individual.

This modernist dead end is addressed by Foucault with the proposition of not one single Utopia, but the multiplicity of Heterotopias or Other Places. Art can help us discover a post-modern multiplicity of perceptions, each shaped by our unique experiences including those relating to sexuality, race, economics, age and society. Foucault, personally, had a terrible time coming to terms with his homosexuality, with suicide and self-harm attempts in his early years. It is possible to see that much of his ideas and writing then become a self-medicating healing, process to radically rally against a dominant, oppressive narrative in all its forms.

Biculturalism in Aotearoa as understood in the Treaty of Waitangi is a good example of how we might think of multiple or ‘other’ narratives occupying the same places simultaneously. Wairua for example might be translated to mean the same thing as Spirit in the Judeo/Christian or even Cartesian understanding, assuming the separation mind and body. However, wairua existed before the arrival of the missionaries, so it must have had a Te Reo explanation completely independent of western comparison. Paul’s work then tricks us with the "treachery of the images" into questioning conventions around our skewed western narrative which is probably at the root of our suffering, despair and depression, leading to self-destructive addictions.

The term "Surplus Reality" also makes me think about Marc Augé’s Supermodernity, or Over-modernity, an over signified world where places have competing meanings that, canceling each other out, leave us with a "Non-Place". Even Augé conceded, however, that this place does not actually exist: a dominant hegemonic meaning will always appear. We might then, consider the gallery as an Other place or Heterotopian space where the self-determined images and sounds provided by Paul come together and provide multiple possibilities of meaning. The viewer trapped in their own reality might self-medicate through the alternate narrative offered by art work. The Gallery then becomes a place of healing: ‘this is not a Gallery’.

Let us now think about the second image alternating with the "mountain". It looks like beautifully back-lit dust or dirt briefly suspended in the air and thrown/blown into the frame. It makes visible to us the movement of air. Could the air movement be caused by a butterfly’s wings on the way to becoming a hurricane? Or perhaps it is a started by a sneeze; an explosion of life.

Paul quotes Rev. Māori Marsden, “Those with the powers and insight and perceptions (Matakite), perceived mauri as an aura of light and energy radiating from all animate life. It is now possible to photograph the mauri in living things.” What is mauri? Again, we might caution ourselves before making a Western translation such as ‘Life Force’. However, many ideas about meaning can invite healthy speculation for a heterotopian understanding across language and culture. Conversely, a systemized Dogma, such as organized religion or a country’s law, is designed close down argument. For me the philosophical ideas of Baruch Spinoza (1632-77), which were highly heretical at the time (almost costing him his life), might well be the closest "parallel" explanation of "mauri" with his clumsy welding of two words "God/Nature". Mauri is the conduit for whakapapa the way in which connection is made to the past, people and the land.

For the Spinozist, here and now immanence of our being alive is all connected to everything through "God/nature". In this rhizomic interconnected world, Paul’s use of 16mm film embodies and illustrates "mauri" in action visually. It is a chemical reaction through optics and motion creating a memory of a moment in time on celluloid film. This film becomes a memory to be played out on a projector, the brain or storyteller. These films bring with them inherent traces and artifacts creating their unique identities. The claw mechanism and gate movement subtly shifts between frames causing visible vibrations. Chemical traces swirl and dance as the film’s grain is clearly visible in the dark shadows. Pioneering filmmaker Dziga Vertov believed that a "cinema verity" or "Kino Pravda" lay in cinema beyond what can be seen, between the frames. Best known for his 1929 film A Man with a Movie Camera, he endeavored to break cinematic conventions already well established by the late 1920s, to take people away from what he called the “institutional mode of representation” or what was quickly becoming the Hollywood narrative. He did this using visual interventions such as multi-exposures, still frames and split screens to shake the viewer into discombobulation as well as situating the camera and operator as the central subject of the film. In contrast, and perhaps the most prescient argument for Vertov would be Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1934). This example "par excellence" of fascist filmmaking with shots expertly arranged into seamless almost invisible cuts to deliver a single destructive political narrative.

Nova Paul throws dust in the air to let us see the wind. Her films help us to an insight about ourselves; like Vertov she places living breathing film in the centre of her work. Her RGB "technicolour" technique also recalls the "Gasparcolor" process of Len Lye’s early direct films, reminding us that film has a genealogy. The multiple exposure amplifies the movement in the cameras gate by three, it is like a heart pumping blood around the body. The abstract shadow cast through a window, exposed over time, is the remembered image entered into our eyes and decoded by the three colour cones in our optic nervous system. This is film talking to you: “we are connected, maybe a mirror image, and we can be many things”. Aware of the possibilities of multiple meaning in self-determined visual images we might piece together our own whakapapa, complete with representational mountains and rivers that say “I Am”.

Utopia then, is not a desirable place. If it really existed, it might have been a fascist state, mental and actual. Instead we are far more complicated; our whakapapa has a unique aura that can be reflected in art where language or writing hopelessly fail us. In Paul’s Surplus Reality the gallery becomes a heterotopian other place of healing where, through communion with the art, we might realign our place in this world.

Tehei mauri ora!