There’s a scene in Jeremy Leatinu’u’s short film Te Whakawhitinga (2022) in which a textured fern fills the wall. The leaf uncurls hesitantly at first before blooming at speed. As I left Māori Moving Image ki Te Puna o Waiwhetū, that image stayed with me. After a failed google attempt, I emailed the artist, who clarified that his work featured two ferns: the mamaku and the kātote. While that image remains specific to Leatinu’u’s work, the generative nature of the fern’s inward curl and long extended lines lingered with me as a resonant metaphor for the kaupapa of the wider exhibition.

Te Whakawhitinga is one of 15 moving image works gathered and presented together by curators Bridget Reweti and Melanie Oliver in the group exhibition Māori Moving Image ki Te Puna o Waiwhetū at Christchurch Art Gallery. From the outset, it is worth noting the exhibition design is exceptional. It might seem a banal observation, but group exhibitions of moving image are hard. For galleries, multiple video works pressure available tech gear and can be difficult to place together. Group shows run the risk of either audio bleed between works, or presenting works in siloed booths, like a successive series of solo shows, neither ideal for a viewer experience. In Māori Moving Image ki Te Puna o Waiwhetū, the works are well spaced, each given sufficient room without divorcing installs completely from each other.

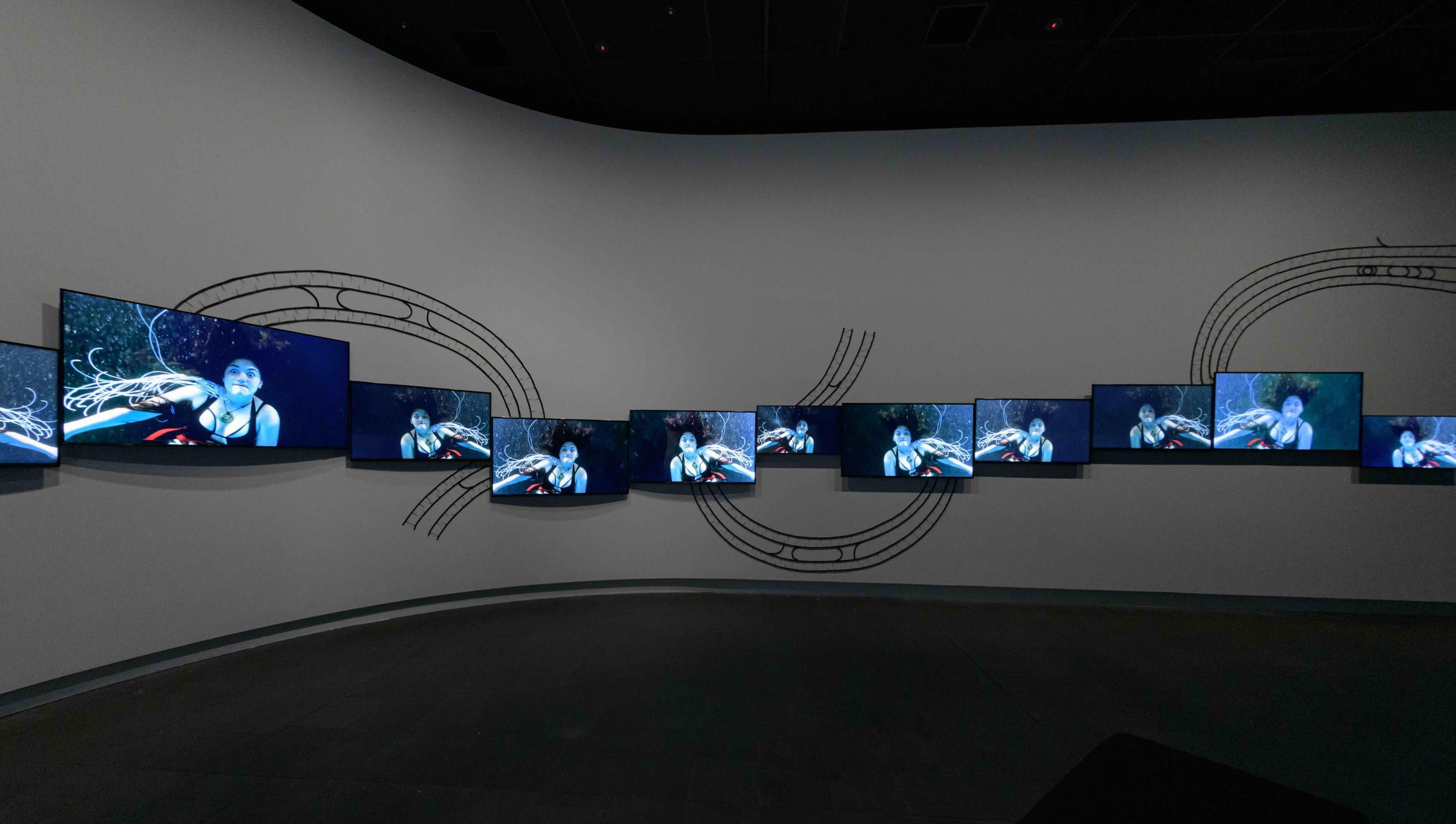

Installation view of Māori Moving Image ki Te Puna o Waiwhetū, 2022.

Perhaps it’s no surprise that the exhibition feels so polished. The exhibition is the latest iteration of a longer Māori Moving Image exhibition series, following Māori Moving Image: An Open Archive at the Dowse and Christchurch Art Gallery 2019, Māori Moving Image ki Te Uru in 2021 and Māori Moving Image ki Te Awakairangi at The Dowse Art Museum in 2022. Even within those exhibitions, iterations were introduced: Māori Moving Image: An Open Archive at the Dowse notably was presented in two parts, with works swapped part way through the presentation.

As indicated in the title Māori moving image ki Te Puna o Waiwhetū (Te Puna o Waiwhetū being the name of the gallery) each Māori Moving Image iteration is sensitive to its presentation venue. This exhibition features a number of Kai Tahu artists. There’s also a strong focus on local place in several works, often informing the artistic choices of video format and display.

Installation view of Ko te wai he wai ora (2021) Rachael Rakena.

Stationed at the first entrance is Rachael Rakena’s Ko te wai he wai ora (2021). A line of 16 screens flows up around the corner and up and down the walls like the curved form of a river or eel. Across the screens play a series of vignettes: the Taiari freshwater tributaries; bubbles floating underwater; a group of young Māori diving and paddling across our view; the Taiari River as it meets the sea, and finally, an underwater kapa haka performance of a pātere. The chant protests the degradation of the water and firmly situates the exhibition from the start within the context of care for the local place. An English translation of the pātere at the entrance ensures no one misses the message.

Watching the work, I became obsessed with catching the moment when an image transitioned between screens. The work functions as a series of repeats, the same footage looping at slightly staggered starting points. If you watch closely, you can see an overlap between screens, when footage in the right of one screen is repeated in its neighbouring screen. It is hypnotic. The same footage ‘moves’ across 16 screens, elongating the image to create a panoramic effect. While the work’s subject and pātere protest the degradation of the water, Ko te wai he wai ora also honours the breadth and expanse of the awa, stretching beyond the confines of a tv monitor or even the edges of a gallery wall.

Further into the exhibition, is Louise Potiki Bryant’s collaboration with Ariana Tikao and Paddy Free, Ta Taki o te Ua / The Sound of Rain (2021/2022). The work considers the impact of climate change in Te Waipounamu. The three-channel installation is structured into three parts, each focused on a different aspect of the water cycle: Waikohu/Mist, Pakapaka/Drought and Awha/Storm.

Throughout the exhibition, te reo Māori is evoked as both a site of knowledge as well as having a distinct aurality that plays off the performative and visual elements of moving image.

Installation view of Ta Taki o te Ua / The Sound of Rain (2021/22) Louise Potiki Bryant.

Also set in Te Wai Pounamu is Jeremy Leatinu’u’s single channel work Te Whakawhitinga. Shot on black and white 16mm film, the work tells the story of a man who left home during WWII for military training in Te Waipounamu. Stationed in another rohe, the history of his ancestors’ pakanga (battle or conflict) haunt the protagonist. Throughout the film, Leatinu’u sets up numerous dualities; the film moves between the past and its current retelling, is narrated by both the protagonist and his daughter, and focuses on the protagonist’s situation between wars, between forms of labour, and between his turangawaewae “up north” and his new settings in Te Waipounamu. These juxtapositions are mirrored stylistically: long panoramic scans of the maunga range are spliced with macro shots of flora and there’s a masterful transition when a mere becomes a spade. The dualities create a sense of inbetweenness, a psychological and geographical unsettledness that perfectly moves the narrative towards its cathartic resolution.

Ko te wai, he wai ora, Ta Taki o te Ua / The Sound of Rain and Te Whakawhitinga all centre te reo Māori. Throughout the exhibition, te reo Māori is evoked as both a site of knowledge as well as having a distinct aurality that plays off the performative and visual elements of moving image. Shannon Te Ao’s three channel work, Ia rā, ia rā (rere runga, rere raro): Everyday (I fly high, I fly low), 2021, sets stills of two performers against the sounds of the waiata Tīwakawaka. The stills are in soft focus. Fragments of limbs, partial faces and blurs disrupt expectations of a clear, linear narrative. The waiata then becomes the spine of the work, the component that drives the works forward.

Installation view of Te Whakawhitinga (2022) Jeremy Leatinu’u.

In Trapped in a Kiss (2021), Ana Iti draws together histories and materialities of text. It opens with the artist exhaling on glass, writing the word ‘HUE’ in the fog of her breath. In the next scene, a letterpress stamps the word ‘ONE’ onto blank paper. Together, the two scenes compare two ‘materials’ for writing with oppositional qualities: the lightness of breath and the solid permanence of ink on a press; the bodily fingered out letters and the mechanical press plates; breath, with its relationship to interpersonal, spoken histories, and printing’s potential for mass distribution.

The mauri of materials and place is similarly a shared concern across works. Robert George’s Horohoro (2019) is an experiment into how a pepeha might be visually represented through film. Shot in his matriarchal tūrangawaewae of Horohoro, five monitors are presented in portrait orientation, suggesting their function as filmic pou. Each screen flickers through the maunga, awa, church, creating a compilation of imagery that suggests the limits of a singular view. In Rākau (2022), Nova Paul presents a large projection film of a rākau tree. Analogue film is usually hand-processed in a chemical bath: here, the artist has developed a film solution made from the tree itself. The rākau appears not only through representation onscreen, but seeps into the film’s very material. Sarah Hudson’s Revisit (2022). Replace (2022), and Return (2022) presented together function as a type of triptych, each part following a different moment in the lifespan of natural pigment. Over the course of three screens, the artist first sources rocks, scratches them to reveal their colour, and then rinses a dyed textile back into the river from which the rocks were first sourced.

The careful attention placed to the connection between materials and their representation is a relation that has been developed through Indigenous film methodologies, at times in direct opposition to film’s colonial histories. These are referenced in Nathan Pohio’s Spectre Echo Landfall (2007). Two monitors bring the viewer close to a photograph of an eighteenth-century ship, an image loaded with historical and metaphorical references to colonial arrival, as well as colonial vantage points in image making. Through a sleight of hand, the still image is made to look like it’s rolling upon shaky waves. An off-kilter instrumental of the ‘Drunken Sailor’ sea shanty playing through headphones suggests something strange might be at play. I watched on repeat, trying to compare the monitors and discern if they were the same footage, coloured and synced differently. I couldn’t catch it. This is what Pohio’s work does so effectively: creates doubt about the veracity of perspectives. The ship never does land.

The careful attention placed to the connection between materials and their representation is a relation that has been developed through Indigenous film methodologies, at times in direct opposition to film’s colonial histories.

Installation view of Christian Louboutin, A Reverie (2020) Lisa Reihana.

Turning our attention from the local to the international is Lisa Reihana’s Christian Louboutin, A Reverie (2020). Commissioned by Louboutin (goals, anyone?), the work mines and presents Louboutin’s various artistic inspirations. An eclectic array of images layer and float over glimmering scenes in this high-glamour scrapbook of sources, scenes and sketches.

Māori Moving Image ki Te Puna o Waiwhetū takes care to avoid essentialising Māori moving image. While there are thematic overlaps across the works—such the richness and complexity of reo Māori, the significance of te taiao; or the relationship between the mauri of an image and its representation—the exhibition doesn’t declare a thematic umbrella. The closest is a paragraph in the wall text:

“Unlike a linear sense of time which has a beginning and an ending, Māori aspherical notions of time start in the centre and move in any direction—a concept that works well with the medium of moving image and its ability to record both time and place.”

It’s an apt introduction. Rather than a single lineage, the exhibition suggests a multiplicity of practices. Māori Moving Image ki Te Puna o Waiwhetū even has two physical entrances. Perhaps an unavoidable feature of the gallery’s architecture, the entrances metaphorically reinforce the exhibition’s argument that there are multiple egress points in and out of Māori moving image. Like the fern in Te Whakawhitinga, artists draw on existing repositories of materials, imagery, language and stretch out in directions of new growth.

This methodology is perhaps best exemplified in Māori Moving Image ki Te Puna o Waiwhetū’s Karaoke room. Here, five artists present karaoke-style lyric videos to accompany pre-existing reo Māori anthems. Described by the curators as a ‘tautoko’ to the musicians, the commission premise is also just plain fun. Presented in an enclosed room, replete with Terri Te Tau’s paua disco light, mics for audiences to sing-along, and an interactive screen for visitors to pick their own songs, the karaoke conceit is a joyful, liberating prompt for invite artists to create accompanying visuals for existing songs. Suzanne Tamaki’s contribution shows her cycling around the streets of Te Whanganui-a-Tara to the tunes of Ria Hall’s Owner, a tino rangatiratanga flag billowing behind her while Luther Ashford’s footage of Taranaki revive fond feelings for the classic Poi E. The premise also gives license for artists to explore the stylings of various fonts. Kahurangiariki Smith’s glitter karaoke-romance aesthetic and Jamie Berry’s digital graffiti pop are well suited to the lyric video format, and Terri Te Tau’s stop-motion animated cross-stitch letters are straight mesmerising. There’s both nostalgia and innovation in these works, generosity for the artists and audience engagement in equal measure. An addition curling and unfolding operates here, with this room having been shown previously at The Dowse as the stand-alone exhibition Māori Moving Image ki Te Awakairangi.

Still from Blue Smoke (2021) Terri Te Tau

From the outset, Māori Moving Image, as an exhibition series, declared a purpose to cement the place of Māori moving image practice within institutions and art histories. Exhibitions that redress archival or institutional gaps are often programmed as one-and-dones, one-shot attempts to make a big enough splash. At best, curators and artists hope for exhibition tours or a publication, but sequels are rare in programming, and rarer still for under-presented practices and histories. Māori Moving Image ki Te Awakairangi refutes that singularity. Like Leatinu’u’s mamaku or kātote, the exhibition draws from existing histories to layer and extend outwards, creating new prompts for future making in the process. Māori Moving Image ki Te Puna o Waiwhetū suggests that Māori moving image can be revisited time and time again, with new threads unfurling, never exhausting itself.