There is a way, suggested by Hito Steyerl, to think about video art. As cinema enters the gallery, no audience can sit out its full duration—instead, it is exploded across multiple channels, so that the wandering viewer is asked to catch limited glimpses of all its parts simultaneously. No final understanding of the work is available, no narrative wound up in tidy conclusion. The result is what might be called a "subtractive montage", in which elements do not combine into a larger whole, but serve rather to interrupt and limit each other.

Peter Wareing has worked both in the long cinema form—notably in his documentary Not Everybody Can Do Everything—and in multi-channel montage. His video-art works, in fact, are often exemplary in taking up the opportunities afforded by a juxtaposition of screens. He repeatedly asks us to pay attention both to the harmonic and immersive experience built up out of multiple channels, and a heightened sense of discontinuity, particularly when the juxtaposed images are otherwise similar.

I am thinking here about There Are Snakes in Paradise (of which one part of three, Oakura Circle, is viewable on this site). The formal device of this work is to knit two camera angles of the same scene, recorded at different times, side by side into a continuous image. The image is disrupted not only by the small awkwardness of fit (conflicting verticals, slight differences in light) but more noticeably by the larger movements of people or vehicles: from time to time someone will step or drive outside of one of the shots in the direction of the "join", only seemingly to disappear into it. This is one example of how one moving image can limit and interrupt the other. The effect is jarring—returning us to the knowledge of the image’s artifice—and uncanny, as if we were witnessing an invisible fold in reality.

Oakura Circle (Part 1 of 3) (2008) Peter Wareing

There Are Snakes in Paradise concerns the impact on surrounding populations of the Ivan Watkins / Dow Chemical plant that operated in Taranaki from the 1960s until the 1980s, and the uncanny effect of the montage is as effective as we could hope as a critical indication of an invisible and poisonous background. Wareing’s montages, that is to say, are no purely formal experiments, but are driven by particular, political concerns.

Wareing’s work juxtaposes not only screen with screen and fragment with fragment, but also image with sound and image with on-screen text. There are also surprising contrasts at the level of genre and texture, such as the combination of documentary realism and enacted melodrama, with all of the latter’s clichés and stock characters: cowboys and military men. His narratives verge on incompleteness, provisionality or incomprehensibility, his logics become irrational as they are pushed to their extreme. Occasionally, as in War-Fi Cowboys, one of Wareing’s "characters" will stop, abruptly, in mid sentence, and hold the camera’s gaze for a few seconds before the end of the shot, leaving the spoken line unfinished. Exterior Signals has a character in a cowboy hat deliver a speech—how, among other things, you tell a good guy from a bad guy—but it is spoken as if being rehearsed, haltingly at first, to an interlocutor who might be a theatre director or a media training consultant. When the narrator of a section of War-Fi Cowboys says "you can compare the dog of war to what you weigh on other planets", I’m sure this makes sense on some level—and still, as the culmination of a thought, it demonstrates sense spiralling out of control. It is, as it were, a discourse of war pushed to the point of a madness that was in it all along.

It is worth dwelling on the juxtapositions and limits in Wareing’s work as a way to think about contradictions in the world: between insides and outsides, between lived experience and invisible systemic (or chemical) effects, between the cowboy myths or ‘rational’ discourses of a nation and their irrationalities and realities, the truths of its foreign policy or of its domestic streetscapes.

This is the kind of thought that we can bring to bear, say, on the character in War-Fi Cowboys, who finds a broken plastic fork and ends up creating a kind of private sculpture by sticking it into a bar of soap. There are all sorts of ways in which we could read this for its combination of high-art monumentality with normally disavowed rubbish—but it also matches up an internal and personal task, one whose reasons we don’t quite have access to, with the documentary texture of an everyday life in which ordinary junk accumulates on the side of the road. Like much of Wareing’s work, it is deeply concerned with its real context—its local streets and bathrooms—while also acting out some private game.

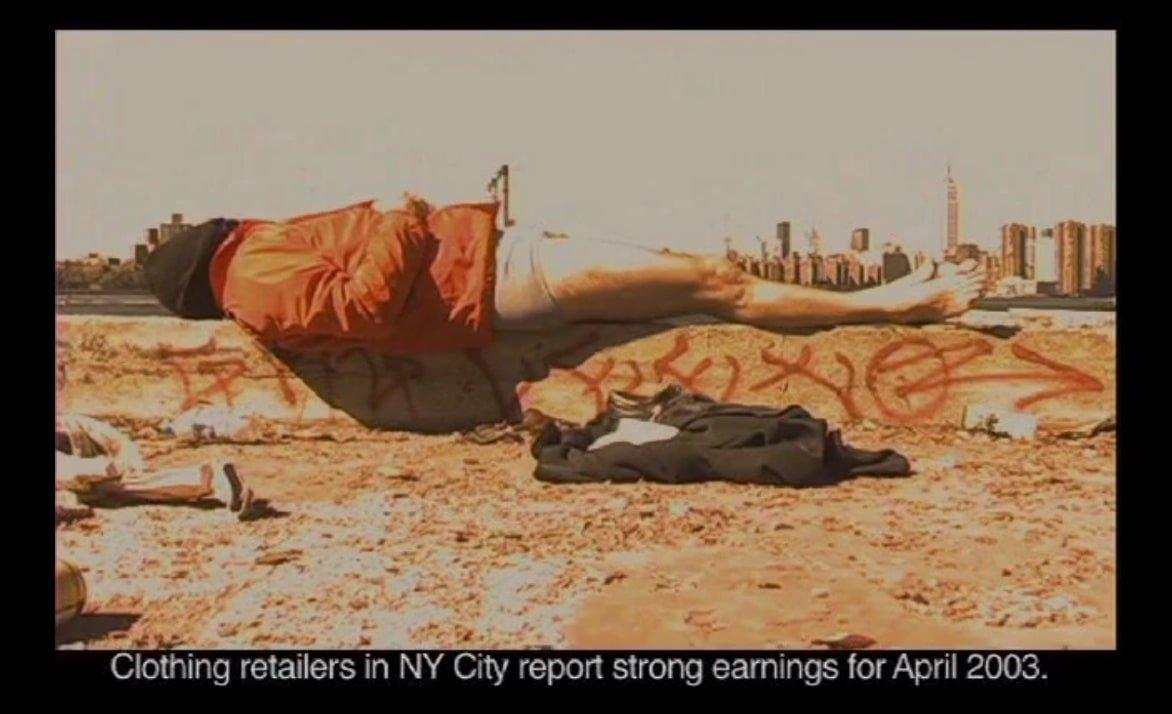

War-Fi Cowboys (2010) Peter Wareing

This is perhaps one of the deepest contrasts to be found in Wareing’s practice. As he has noted in his online notes to A Russian Ending, "[c]rossing melodrama with the documentary form is one way of looking at our post-Fordist economy where the cognitive freelancer must maintain, at the very least, slightly exaggerated enthusiasm for whatever work my be available in their given profession." The freelancer—the paradigm of the contemporary, "free" individual, released from the institutional contexts of the past—is at liberty to follow her "mad" or "creative" dreams, but is at the same time stuck in the midst of an objective "gritty" reality, forced to act out, in an attempt to attract credit and exposure.

A Russian Ending (2012) Peter Wareing

No discussion of Wareing can be complete without further discussion of Not Everybody Can Do Everything, a feature-length documentary about the residents of a Manhattan home for the blind or visually impaired with developmental disabilities. The film follows the 14-year historical arc of its filming. As such, it has all the impact of a kind of minor narrative, in which there is little by way of plot, but a great deal by way of life’s movements: walks, meals, encounters with family, and most movingly, some of the inmates’ deaths. It has the cumulative effect common to much documentary: our building understanding of and relationships with its subjects, the arbitrary cycles of mood and season. It also shares concerns with the more formal video works, alternating its interior and exterior scenes (with occasional glimpses up to the tops of skyscrapers, views inaccessible to the inmates) and emphasising the closure of a world of dependent subjects. Wareing is both sensitive and reflexive in his entry into that world, which comes across as both another limited perspective and one with its own surprising expanses of thought and possibility.