an even hand is a smothered tone

Trying to find ways to meaningfully inhabit both our bodies and world will have us searching for new experiences and testing our limits. Following lines of thought, tinkering with forms. This is what structures the practice of Phil Dadson. His work embraces a wide range of media including video, performance, audio, drawing, and film. At once an affirmation of being-in-the-moment and an attempt to engage with the complexities of sound, motion and world, it’s a question of being open and responsive. In affirming the importance of mindfulness, Dadson’s attention to both embodiment and world sets the tone for his artwork and draws you in.

As indicated by the title Parallel Harmonies, the work in Dadson’s exhibition plays on the relations both within and between works. It is a way to derail somehow the atomistic stance of the autonomous art object. This is achieved in an accumulative manner, where through recurring visual motifs and overlapping audio, Dadson’s exhibition at Trish Clark Gallery includes 16 individual works, but quite literally builds layers to achieve a fully immersive environment. It’s as if the hushed stroll of art world consumer habits and viewing conditions has been superseded by the ripple effects of digital culture.

The quick climb to the gallery’s raised space reveals a three-channel video and sound work The Fate Of Things To Come (a conference of stones) (2013). The screens display alternate shots of Dadson unleashing the sonic qualities of stone instruments: a tradition which dates back at least 2,500 years. The work turns heavily on tripling. Each of the three screens plays a succession of brief, individual performances, fading in and out of legibility, but taken as a whole creates a sophisticated composition; resonating stones speak with a voice that is both familiar and ancient. Here at Trish Clark’s space, the work is simultaneously visible as three wall-mounted screens in a line, different from its alternate exhibition mode as a suspended equilateral-mount formation (requiring the viewer to circumnavigate the work).

Installation view of The fate of things to come (a conference of stones) (2014) Phil Dadson. Photo by Jennifer French. Image courtesy of the artist and Trish Clark Gallery

The composition itself builds and swarms with all manner of tapping and scraping, generating intricate rhythmic detail and conjuring a raucous and subtle array of sounds. The tonal variations in the rock-strikes aspire towards the condition of melodic motifs. In one passage, two people cradle stones in a lavalava, moving it like a washing machine set to "gentle agitation"; a masterly sound essay on limitation as the source of possibility.

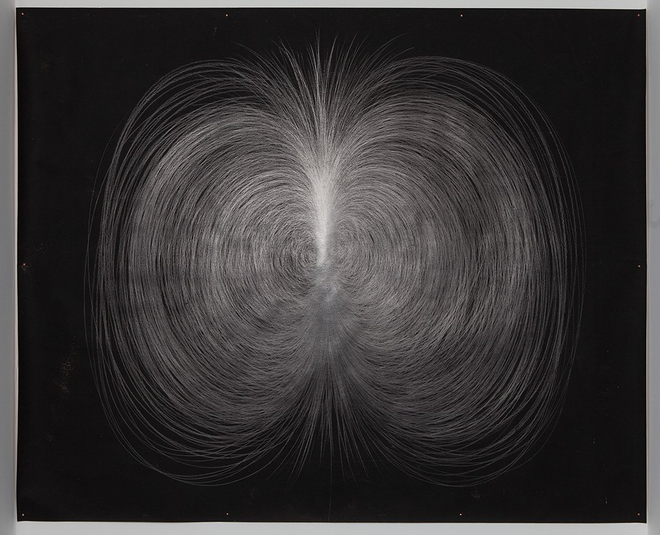

Nearby, Soundtrack #12 (1987) consists of two elliptical vortexes drawn on black painted paper. Solid gestural strokes of graphite provide a locus of subtle tonal gradations against the black ground. Two dark, contiguous air-sacs emerge from the agitated throng of lines bringing to mind a line from the Ted Hughes poem, Crow (1970), “black the lungs/unable to suck in light.” The succession of directional lines in Soundtrack #12 appear to recede into space in a series of sinking ripples. Before long, the eye becomes alert to a seemingly endless, unsettling movement within the image. The search for an optical resting place is repeatedly thwarted and deferred; the mesmerising form leading to an uncertain destination.

Installation view of SoundTrack #12 (1987) Phil Dadson. Photo by Jennifer French. Image courtesy of the artist and Trish Clark Gallery

The search for an optical resting place is repeatedly thwarted and deferred; the mesmerising form leading to an uncertain destination.

The diagram is one from a series of "sonic energy field" drawings from the mid-1980s entitled Soundtracks and Groundplans. For many of these works, Dadson used paper roughly the size of his body and worked across it in an even handed, yet intensely kinetic manner. These works show directional lines of force—recurring and intersecting lines—that seem to sound the depths of the earth, registering the electrical currents which move underground and through the oceans. The series evolved directly from ground plan drawings devised for From Scratch performances, such as Gung Ho 1, 2, 3D (1985) which employed the making of a triadic floor plan to start the performance.

Interspersed through the central gallery, Dadson presents three single-channel videos made recently in one of the earth’s driest places, Chile’s Atacama Desert. Desert Project (2013-ongoing) extends motifs explored in Dadson’s Polar Projects (2003-2005), examining the natural world, with an emphasis on extreme locations that are beautiful but desolate, awesome yet dangerous. Many of the structural patterns in these videos, including the upturned artist himself, are innately repetitious and inverted, overturning and up-righting themselves. The videos read as a personal account of the specificity of place, which is also a struggle with place, and of history, corporeality and time.

Desert Tomb (Atacama) (2014) Phil Dadson. Photo by Jennifer French. Courtesy of the artist.

It’s as if the hushed stroll of art world consumer habits and viewing conditions has been superseded by the ripple effects of digital culture.

Desert Tomb (Atacama) (2014) shows camcorder footage of barren landscape, consisting of salt encrusted red clay, shot some 15kms from San Pedro de Atacama. Structurally, the video is a tour de force—a rapid succession of close-up and long tracking shots. The images could well be interpreted as an example of what Gilles Deleuze called an "intensive mapping"; an embodied cartography that privileges movement, response and affect over the tracing of established, fixed points.

The camera work rescues the landscape from touristic viewing by its low, swish pan, forward tracking revealing a lizard-like perspective of a dry lake. Similarly, Dadson’s brief, vertiginous shots of a gorge wall are a giddy study of differentiated sand wall formations. The movement of the frame reveals the landscape as an assemblage of relations; strata patterns, dark wall crevasses, sloping outcrops, salt-caked sand walls, lustreless red earth tones, irregular ground fissures, and vast, indistinct plateaus. The pace of the video is well complemented by textural, rhythmic layering and interplay of the score, composed and performed by Dadson on his self-devised string instrument the Bamboo-barrelzitherimher.

Headstamps (2014) shows a headshot of Dadson performing a headstand in a hot desert gorge. It plays on doublings and echoes. Dadson’s lengthy headstand recalls the witty absurdity of Edwin Wurms’s One Minute Sculptures, in which people are choreographed into precarious poses with familiar objects. But perhaps it’s better to think of Dadson's action as a more serious endeavour, recalling Saint Simeon the Stylite caught up in an endless loop between his own risky position and the constant and imminent perils of the desert. The most obvious evidence for this is the way in which he performs his headstand with a ritualistic dedication, proceeding with an elaborate breathing/body exercise, before slowly planting his fists. Or from another point of view, the prolonged headstand—a grim battle against gravity—is a symbolic response to the shortcomings of an unquestioning national pride, overturning the confident upright stance of New Zealand neoliberalism and cleverly inverts what Allen Curnow called “the trick of standing upright here.”

Arid Edge (Atacama) (2014) is a point of view, single shot taken while cycling a straight stretch of road. The impulsive movement of the frame ensures that the artist’s linear motion is fragmented into a dizzying sense of space. Filmed with a handheld camcorder that alternately pans, swoops and inverts. Dadson’s highly accented shooting reveals close ups of himself, his bike wheel and long shots of the salt flats. It becomes impossible to follow the movement of the camera without being hypnotised, at one point, by the constantly shifting pattern of his spinning bike wheel, recalling the optical effects of Marcel Duchamp’s Rotorelief Discs. The forward impetus of the bicycle, combined with the unpulsed rhythm of the moving image, disrupts any sense of homogenous space and time. Dadson intriguingly reacquaints us with interiority, revealing patterns of consciousness rather than linear sequences of events in the external world.

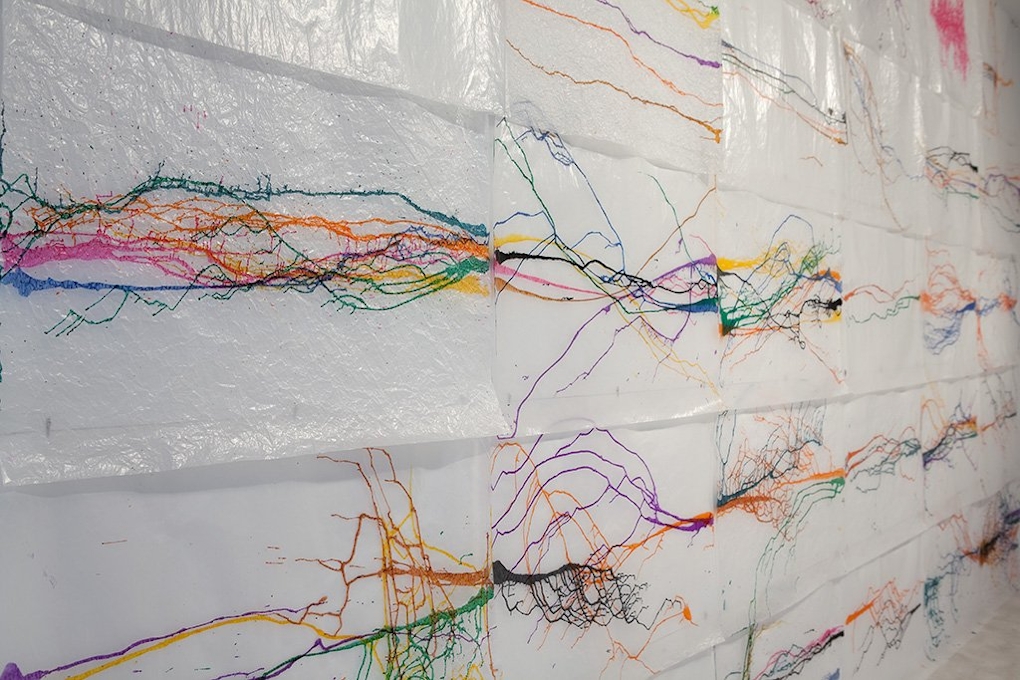

The painting series January Music (paper, hand, ink, eye, wind) (2014) is a visualisation made in response to natural sounds and elements. In the exhibition notes Dadson explains the structure and discipline behind the making of the work: “A visual music: one sheet per day through the month of January 2014.” The ink images, painted on translucent paper clipped to a wire rigging, fill a single gallery wall in a regular block pattern (one work hangs alone on the adjacent wall). Thin, multicoloured lines spill and branch through the drawings resembling cardiographs, lightning strikes, and fibrous root systems. Here we experience the visual in all its volubility; the images almost intoning in a snapping, crackling rumble.

Installation view of January Music (2014) Phil Dadson. Photo by Jennifer French. Image courtesy of the artist and Trish Clark Gallery

The movement of the frame reveals the landscape as an assemblage of relations: strata patterns, dark wall crevasses, sloping outcrops, salt-caked sand walls, lustreless red earth tones, irregular ground fissures, and vast, indistinct plateaus.

In the main exhibition space, the eight-channel sonic sculpture Octet (2014) lies low on the floor. Made in response to the gallery ceiling, Octet uses the architecture and acoustics of the gallery to create a clarion call of tones, textures, and voices. Eight conical horns—the sort that look as if they were reconstructed from a Luigi Russolo fever dream—are mounted to a hefty, circular steel pipe hugging the floor. The sculpture is a glossy, powder-coated steel form in a fire-engine palette of intense red and cool greys. Look closer, and the horns encase 3-inch speakers, calling to mind both vehicular and loudspeaker audio systems.

Installation view of Octet (2014) Phil Dadson. Photo by Jennifer French. Image courtesy of the artist and Trish Clark Gallery

In the soundtrack, a 10-person ensemble recites 15 pieces, including the Islamic call to prayer and Jewish prayer cycle, in a thoughtful response to the gallery architecture, referencing its former use as a Jewish Synagogue Sabbath school, and its octagonal-shaped ceiling feature which recalls a classic shape formation used within Islamic architecture. Octet is an intrinsic component of the exhibition; the audio work utilises and animates the architecture itself with a complex yet cohesive layering and mixing with the aural ambience of nearby works. A Max patch software program, authored by James Charlton, was devised to control the synchronised supply of 15 sonic interventions—each recorded as eight channel audio mixes—to the eight speakers, sending tones and rebounding notes against the gallery’s surfaces and corners. Just as listening to Octet conjures up the sense of place in a more immaterial, affecting sense—one that pleasingly displaces me—it uses acoustics to announce itself with an immediacy that is sculptural, physical.

Harnessing the ability of images and sound to create perceptual shifts, Dadson’s art is ultimately one of paying attention. On a deeper philosophical level, his work examines the way in which consciousness is formed. The subject, either represented or not, is always present as one node in a field of forces that resound again and again in his work. In the end, his practice can be seen as attempting to remain present to ourselves as we become increasingly entangled with non-human nature.