If you asked Martin to define his practice, he’d call himself an experimental film-maker. Sometimes I thought he was overlooking his impulses as a documentarian. In Martin’s CIRCUIT bio Canadian film-maker Mike Hoolboom called him "an anthropologist of the heart". This last description nails it.

Take For Dots (2008), one of his portraits of African American street culture in Chicago. Early on Rumsby introduces the film on the voiceover; "Dot showed me how things worked and looked after me on the streets. I decided to make a film about her. A home movie about the homeless".

Dots is the central character but the film follows a variety of people who circle in her orbit, hovering at the edge of poverty. What’s remarkable is that amongst the heartbreak and despair there’s so much joy. Firstly there’s music—which Martin loved—then there’s poetry and radical optimism. I’ll never know how Martin ended up in this Chicago realm, but the people he meets are at ease with him and his camera.

For Dots (2008) Martin Rumsby

In a later work shot back in Manurewa, New Zealand, Eye I Aye (2014), Rumsby waits for two neighbourhood personalities to take up their daily vigilance on a public bench. Here again he describes people on the margins – “At a certain point in life most people choose energy and application to define their character. Dida and Erena decided to bypass this route, settling on a life of straightforward being”. Rumsby quotes French writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline - “Everything in the end will turn into the street”. Over ten minutes we see rain, pale sun and the passing of time. The key moment though, is near the end, where Rumsby steps in front of the lens to clean it. For a moment we are in extreme close up with what, arguably, is the true subject of the film.

Eye I Aye (2014) Martin Rumsby

In the canon of New Zealand experimental film Martin had many lives. In the 1980s he toured a programme of local Super 8mm film works around North America. Along the way he collected other works by North American film-makers he considered exceptional and he showed them, too. Prior to that he had been part of Alternative Cinema, the Auckland Film-makers Co-operative, whose more formal successor would become the Moving Image Centre in Auckland. In the 2010’s he curated a DVD of New Zealand work which was published with an essay in Illusions magazine, designed as a resource on experimental film-making for local film-schools. Of course the film schools never took it up. Nevertheless, Martin remained a prolific writer who championed a history of local experimental film-makers where no other institution had done so, identifying a lineage of artists from Joanna Paul (whom he memorably described as ‘the first lady of New Zealand cinema’) to Darcy Lange, Merata Mita, Barry Barclay, Kathryn Dudding, Gavin Mbali and others.

In a recurrent theme in his writing, he also pulled no punches in lamenting the lack of institutional support for artist practice in his home country. This from the essay Before (2003), first published in New Zealand in Illusions Magazine, now on Academia.edu;

“The history of artists’ cinema in New Zealand is one of founding mothers and fathers working independently and often alone. That many died or retired young points to the severity of their calling”

He also railed against what he saw as an institutional bias towards academia, at the expense of exploration;

“For the most part, the New Zealand scene is unrelentingly institutional, skewed towards academic artists and institutional interfaces. Unless an independent artist can successfully produce for the market then her work will be overlooked.

When a culture is reduced to forms, artists do not have to strive for excellence but rather for merit gained by correctness. In an environment which allows no room for outsiders, adventurousness is diminished and artists are pushed away from individual expression and excellence”

I first met Martin sometime in the 2010’s when I invited him to show his North American touring programme of Super 8mm work at the New Zealand Film Archive in Wellington. As much as he longed for a sense of community, and was endlessly driven to make films, I soon discovered he was often at odds with local institutional structures.

After the screening Martin was asked what had happened to a film about Theo Schoon he’d been given a government grant to finish. Martin replied he’d been distracted by other projects. At the time, Martin had not long returned from North America, and would become involved with a local group of film—makers in Auckland, seeking to affirm a common sense of practice under the banner Floating Cinemas. The group didn't last. Martin began academic study in Hamilton but left denouncing the institution’s Ethics Committee for ‘bullying, harassment and obstruction’.

But in some way, Martin's values were all geared towards the artist, even if they sometimes appeared contradictory. In a 2013 CIRCUIT Symposium he happily abandoned the topic to ask "Why aren’t film-makers paid for their work?" Later, in 2015, I flew him to Wellington to review a Ken Jacobs screening. He arrived in town in the morning but turned up late for the opening film, though he’d shot some great footage of his own that day on the waterfront. Sometime in the 2010s at Snakepit Gallery in Auckland he organized and introduced a documentary on American film-makers George and Mike Kuchar. I asked him where he hired the film from, he breezily replied; "Oh I just ordered a DVD off Amazon!"

All of this was classic Martin. I sometimes wondered if he preferred the freedom of the outsider. I was grateful he let CIRCUIT show his films on the website and in our public programmes. When we gave him a commission in 2018 to make SOJOURNS, he happily exclaimed - "At last I’m being paid to make work".

SOJOURNS (2018) Martin Rumsby

Long after his return to New Zealand, Martin would continue to champion North American work as a benchmark for experimental film. He celebrated what he saw as it’s adversarial and political stance, and lamented it’s absence in New Zealand.

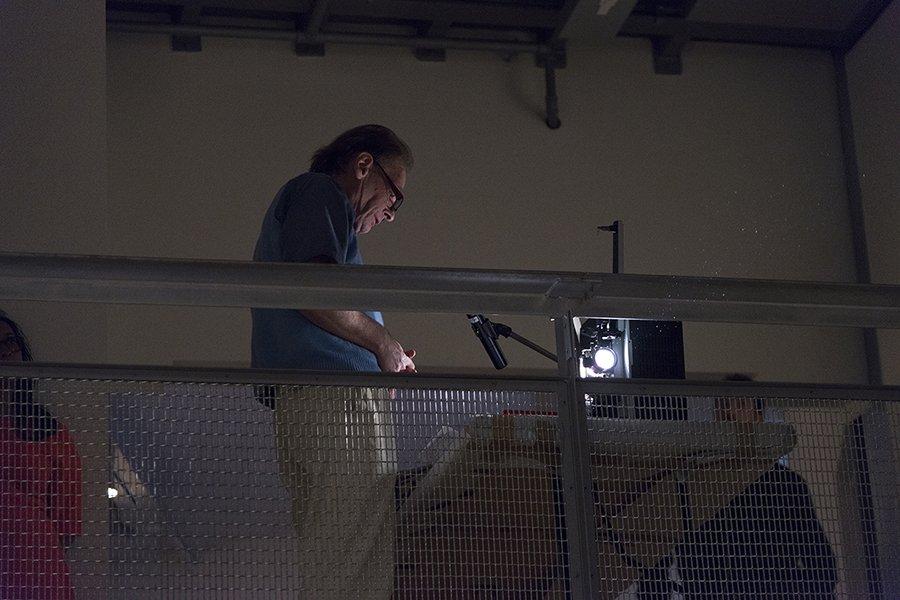

In 2014 he was asked by the Adam Art Gallery to open the exhibition Cinema and Painting with a performed reading of the classic Hollis Frampton piece A LECTURE (1968). It was a moment of recognition, and I was delighted to see the hushed gallery listen to Martin deliver Frampton’s treatise, which matched both Martin’s own sense of humour and lent some insight into the oppositional roots of experimental film-making;

“We are, shall we say, comfortably seated. We may remove our shoes, if that will help us to remove our bodies. Failing that, the management permits us small oral distractions. The oral distractions concession is in the lobby”

I had periodic correspondence with Martin during his past 2-3 years in Vietnam, Cambodia and elsewhere. He made a lot of films during this period, mostly very diaristic, celebratory films of local culture and people, and the effect of Covid on the inner city. I always thought of these as preparatory sketches for a film he might make when he was deeper in the culture. Now I need to watch them again.

I guess it’s not uncommon that when we revisit artists’ works we find things we’ve missed. Last September, when we were remaking the CIRCUIT website, I watched one of Martin’s older films Driveway (2006). It had been on the website for 10 years, never shown publicly and I have to confess it’s not a work I had paid too much attention to. But on this viewing, both myself and my colleague Thomasin Sleigh were blown away. I wrote immediately to Martin;

"I just watched Driveway again, for the first time in years. Holy shit, it's a masterpiece! What a movie."

Thomasin was more lucid;

“I loved that interplay between viewer, lens, window, seating, screen, remote control, gaze, horizon line, perspective... “

Driveway is a one shot movie set in a lounge. In the mid-ground is a couch. Behind it is a window, and through this we see people approach the house. We hear voices off-screen. Knowing Martin’s deep interest in the international avant garde, I asked if Driveway was an allusion to the classic Michael Snow film Wavelength (1967). His response was typically generous, showing his deep knowledge of experimental film history, other wider cultural and artistic references, and acknowledging the ongoing homage in his work;

Martin: Yes, definitely a rumination on Wavelength and Canadian experimental landscape films. The Driveway is like a long lens, the movement is from straightforward documentary to abstraction then back again - a movement through art thinking from realism to abstraction and then beyond. Maybe there is a movement from objectivity to subjectivity (sort of) and then back again. We see essentially the same thing but it changes (without actually changing) - our perception of it changes, and we know why.

There are a couple of other things too - an element of theatricality as suggested by the curtains (as if curtains for a stage or sceen) and the leather seat, as if cinema seating. But instead of looking at the event of cinematic interest the couch is placed to look away from the view and what we are looking at. There could be an element of social criticism here - that people do not look at and engage the world directly. Instead, they are looking inward, away from the world, maybe they are watching TV or even the filming event. You can see traces of their presence at times on the couch, little depressions where people have been sitting. (Another absence). The window is also a barrier between us and the world but also refers to the glass camera lens.

Farewell Martin, we will miss you. You leave a legacy of films, writing, enthusiasm, friendship and within all there’s more to discover. Thank you for sharing so much. One last word from fellow traveller Hollis Frampton;

“Our rectangle of white light is eternal. Only we come and go; we say: This is where I came in. The rectangle was here before we came, and it will be here after we have gone.”

Driveway (2006) Martin Rumsby