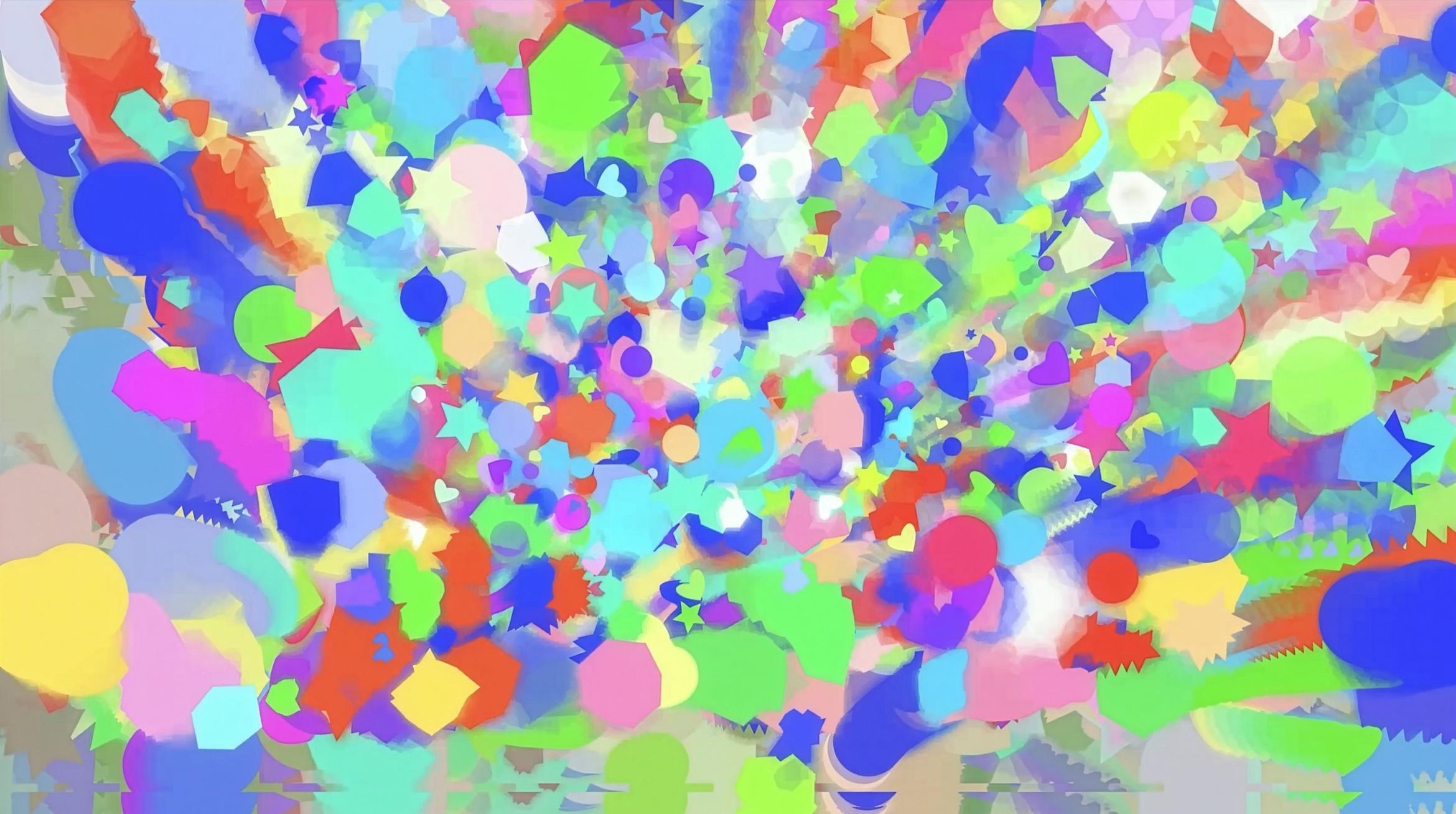

Suddenly, kaleidoscopic chaos bubbles and pops across the screen. Pouring out at us are lines, dots, stars and hearts in pink, green, blue, orange, pastels, neutrals, darks and brights. They scream in silent excitement, capturing our curious gaze. It’s like standing in a meteor shower of confetti. This is Shannon Novak’s Generative Dopamine Loop (2025) commissioned by CIRCUIT for the Masons Lane public art screen.

Novak began his exploration of new technologies in 1995, when he launched the online gallery Frame Rate. Technologies and art have intertwined in his practice ever since. He says being young and online in the ‘90s has given him a strong emotional link with internet spaces. The anonymity and connection of the web allowed him to explore his queer identity and self through online personas.

Novak’s practice often queers space, or light, as in his Refractions installations from 2011 onwards, where stained-glass-like works played on shape, colour and surface. His digital works explore emerging technology’s potential to queer space, exposing their potential to do both harm and good for queer communities and other disenfranchised groups. Since 2022 he has produced works with a particular focus on how AI understands and represents queerness. These digital works are curated by Novak under the title Velebit, what he labels a ‘hypothetical organisation’, imagining the artworks as a body of research on emerging technologies, some of which do not yet exist. Novak is also the director of the very real organisation Artificial Intelligence Safety Forum (AISF), a research group that assesses and ranks the safety of various AI applications, in light of AI’s link to several deaths and violent incidents. We can view Velebit as an omen of the future of AISF, nudging us towards creating and consuming technology that is regulated and safety conscious.

Generative Dopamine Loop emerged from a Velebit work, Adaptive Space (2025), which imagined a new technology, the ‘Brain Computer Interface’ (BCI) and a hypothetical application for it. The screen shows a series of AI generated rooms and spaces, seemingly in response to the imaginary user’s brain activity, ensuring the user is always in the most ideal place and an optimal state of bliss. Generative Dopamine Loop expands on technology and satisfaction, looking to a current example, social media. Data was pulled from a social media post made by Novak and animated in real-time, with the amount of likes and their speed (amongst other variables) resulting in each shift of colour, shape, movement and size seen on screen. The resulting animation visualises the dopaminergic pathways lit up by algorithmic bliss, exploring, perhaps, a BCI that we are already linked up to.

-(2025)-circuit.jpeg)

Shannon Novak, Adaptive Space (view) (2025)

In the lane, the Loop never ceases, but in its chaos, there is a sense of serenity, calm. If I stuck my hand into it, I think I would feel the pull of a current, a tug towards something. It is always nearly going there; it is nearly sometimes enough; it never sits still, always going, never arriving. Searching again and again for the perfect combination, the perfect hit of aesthetic satisfaction, of pleasure, the perfect hit of dopamine. Staring into it I feel an overwhelming need to dust the surface, to push aside the chaos like a curtain, to find out what’s underneath. The Loop shudders, a little shiver in the flow, the way a website jolts to refresh. Something is watching, updating, measuring, optimising.

Shannon Novak, Generative Dopamine Environment (2025)

Harlan Ellison’s 1967 short story I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream depicts the insatiable intelligent machine, ‘AM’, driven mad by its own creation. AM was created as a tool of war and solely exists to execute precise destruction on its creator’s enemies. But this limited role was never going to be enough for the perfectionist machine. AM keeps the last remaining human, the protagonist Ted, alive, solely to continue to enact revenge on him. It strips Ted of his human form, making him a grotesque blob of skin with eyes. Yet it leaves Ted his human mind, so Ted understands and is aware of his eternal torture. Ted’s existence and intact intelligence mean AM never has to think, even for a moment, about its own. AM keeps Ted almost, nearly, close to death. Ted lacks a mouth, and all he wants, needs, is to scream.

Here within the Loop, we sense a presence, perhaps our version of an AM, one that begs for us to look at it, to love it. The Loop cries out for attention in bursts and fizzles. It begs us to stay, refusing to be still, to end or begin, refusing to let us be bored.

Novak has captured the rhythm of social media, the way the algorithm entraps us online with hit after hit of unsatisfying not-quite-enough-ness, scrolling endlessly in search of increasingly more dopamine. If you loved me… you would watch this ad. Tell me all your secrets… if you loved me… you’d let me sell them. Novak forces us to face an AM that, instead of controlling and contorting our bodies, controls and contorts our minds, reprogramming our impulses and habits. Wake up, look at me. Bored? Look at me. I will make sure you never feel bad again. You will never need to scream.

Humans are more machine than ever in thought and body. Technology mediates how we move through society, how we feel about ourselves and others. We ‘see’ through a camera lens, and ‘think’ with AI chatbots. We form and maintain our most important relationships via social media. My arm does not fully extend until I have a phone in my hand. Almost 20 years after Ellison’s AM, Haraway’s 1985 essay A Cyborg Manifesto encourages us cyborgs to embrace technology wholeheartedly, to live without categories like human vs machine, and in doing so move beyond the “matrix of complex dominations” holding us to hierarchies of oppression. [1] She calls for us to love our blurred boundaries and to embrace our cyborg selves.

I reflect in front of Generative Dopamine Loop, as each burst of dopamine on screen corresponds to the burst in my mind. I can feel Haraway’s call within my own body. After all, it was humans who created the algorithms keeping us glued to our screens, humans who created this AM to beg for love. By denying our own interwoven nature with the algorithm we deny parts of ourselves as they are forming, making it impossible to recognise ourselves, and impossible to work with and not against the technology.

Through this perspective, the Loop exposes the AM sitting snugly inside of us. We are both captive and captivator, struggling to uncouple with our AM. In its constant, flickering, insistent chaos the Loop wears at us. Look at me, love me. We cannot remove these entanglements with machine. We can examine them though, see them for what they are. The shapes shift, collide, recoil, dive. “I can programme you not to scream.” The Loop’s silent almost-ecstasy writhes forever on.