Though not specifically about or rendered by AI, the three works by artist Susu 蘇子誠comprising their exhibition Skin in craters like the moon speak to one of the main cultural anxieties in AI’s advent: the anxiety that, much like the gatekeeping theologian’s fear of the printing press, authentic human expression is somehow threatened by the synthetic image. For Susu, this couldn’t be further from the truth. In fact, with slippery digital imaging the artist deliberately creates opaque synthetica that, more than anything, allude to the intimate and phantasmatic doubles every human makes of the world around them. Call it cognitive mapping through a lens of Studio Ghibli-inspired pastorals, seasoned with the utopian textures of video-gaming.

That the show’s name is taken from a Lorde song, whose arguably industry-planted stylings minted pastel goth BBE (Before Billie Eilish), means more here than a camp tethering to pop culture. The song in question—'Team', off 2013’s Pure Heroine—describes Lorde’s own fantasy version of Aotearoa New Zealand and its cities which, despite being dwarfed by global metropolitan standards, remain real cities with real people. Scrappy, perhaps, measured by the densities and glamours of London or New York, but charming—maybe because of their very shortcomings alongside normative yardsticks. Lorde’s verses assemble a citadel of fantasy ruins, of memory; in the way that Susu’s work is a rendering of memory as a sentimental hallucination, a mirage of disparate impressions cobbled together to form lush interior landscapes. Across the exhibition, Susu builds a deeply personal and private space, synthesised from cherry-picked encounters with a shared reality hybridised by history, culture, and technology. We see this in the meticulously animated constructs of video work Coco and Aiai 可可愛愛 (2021-22) through which we wend from the perspective of a disembodied observer. A virtual camera-eye hides in the reeds of a sun-dappled marshland, then canters through misty flora, all accompanied by Susu’s subtitled grief for their titular cats—a cunning vehicle which the artist uses to launch an expansive argument for the slipperiness of belonging.

Susu 蘇子誠, Coco and Aiai 可可愛愛 (2021-22). Image courtesy of the artist.

Early in the work, Susu describes their sadness about cats Coco and Aiai, who are long dead but inextricable from early childhood memories of their home country Taiwan. After opining how elusive and unattainable a sense of belonging is, Susu wonders if either cat ever truly felt it, if they were aware of their tether to Susu’s family, or if perhaps they were benignly indifferent to how totemic of home they’ve since become. A work about cats might seem flirtatiously twee, but only because the artist essentially effaces themselves for their own self-indulgence here—"it was the saddest thing I’ve ever experienced, and that’s sad too"—before following their dead cats down a turgid rabbit hole of introspective musings: on home, on the psychological exhaustion of chronic nostalgia, on the free-floating guilt of having left Taiwan at all. The cats, then, are stand-ins for the family they’ve left behind, for the support networks sloughed off for the promise of another life. If they’re haunted, it’s not by cats. It’s by the collapse of everything that could’ve been, all those possibilities foreclosed in the choosing of a migratory path.

Susu 蘇子誠, Coco and Aiai 可可愛愛 (2021-22). Image courtesy of the artist.

Susu 蘇子誠, Coco and Aiai 可可愛愛 (2021-22). Image courtesy of the artist.

With Remember To Dive 回溯潛水 (2022), the video screen panel is taken off the wall, sitting on the floor like—pardon my millennial-ness—a Harry Potter Pensieve (cited with full condemnation of author J.K. Rowling’s anti-trans red-pilling). To the unaffiliated, a Pensieve is a magical scrying device used to scrutinise memories. So, like the show’s larger remit of intimate memory, the work is a proxy-navel that wills viewers to gaze into it like they might their own private trove of recall and impression. And like the Pensieve, its contents are a mix of reality and fantasy, of memory flecked sometimes indistinguishably with dream, and the oblique desires which sometimes refute that distinction. In the artist’s swirling-silken imagery, we’re treated to a stew of Susu’s inner life rendered as viroid fluids, perhaps a mirrored reminder that at a certain level everything internal carries the same weight, no matter how tethered or untethered to concrete objects and experiences. In memory, objects lose their weight, are smelted down into the quicksilver of fictive bias.

-animation-video-8-45-min-image-courtesy-of-Te-Tuhi.jpg)

Installation view, Susu 蘇子誠, Remember To Dive 回溯潛水 (2022), Te Tuhi, Tāmaki Makaurau, 2024. Image courtesy of Te Tuhi.

As in Coco and Aiai 可可愛愛, Remember To Dive 回溯潛水 has text guiding us through esoteric colours and lines resembling bacterium, only occasionally congealing into recognisable objects. The work is a fugue of colour and form. Fittingly, the confessional narration describes a swimming practice: "sitting in pressure at the bottom of a pool ... I used to train for this ... each stroke is definite, sure, with ambition." Where Coco has a clear setting and comparatively linear narrative, Dive does deep work, unfolding like that other work’s murky unconscious. If Coco is the dream journal, then Dive is the dream itself, the raw quanta of feeling. Later, Susu describes Tudigong, a regional Taiwanese god of earth and soil who requires consulting before a migratory transition to foreign lands. Through Tudigong the swimmer image evolves, stroking energetically against a dysphoric current of displacement and cultural alienation. There’s a happy denouement though—an extended sequence of fireworks—a rewarding finish to the work’s tantric pace. Yet it is still marked with a presiding sadness, as if the spectacle was actually hollow. "We gather dead stars and make our own ... I cannot make up words but I can memories ... it would be useless to blow out a sparkler as it kills itself once there’s nothing left to be burned." Rather than celebratory then, Susu’s fireworks may instead be an adamant schizoid hallucination born of homesickness and loss. Resilience by another name. But for the artist, resilience is a gentle thing. It doesn’t lash out, nor does it resign. It merely prettifies what it can with escapist tendencies.

Susu 蘇子誠, Remember To Dive 回溯潛水 (2022). Image courtesy of the artist.

In the wider context of diaspora, which Susu’s work alludes to with a gossamer touch, the artist finds themselves in the slippage between ideals: ideals of home (Taiwan), and the ideals of a new place (New Zealand), to where they moved armed with nothing more than a Lorde song as psychic armour, as expectation. Which begs the question—as the work does so eloquently—what images spring to mind when we say Taiwan, or New Zealand? Are these images accurate? And if so, where do they come from? Maybe it’s like DNA, with some opaque principle that nominates select sections of code as valuable while a majority is considered junk.(1) Either way, the tacit enquiry is whether or not every life that begins and ends in this place is valid enough to be integrated within the national idiom. Does this characteristic affect have to be prescriptive? Can it be porous and reciprocal? Put another way, is the hyperspace of our country’s self-esteem a branding exercise or a collective creative writing project?

Susu 蘇子誠, Remember To Dive 回溯潛水 (2022). Image courtesy of the artist.

Susu 蘇子誠, Remember To Dive 回溯潛水 (2022). Image courtesy of the artist.

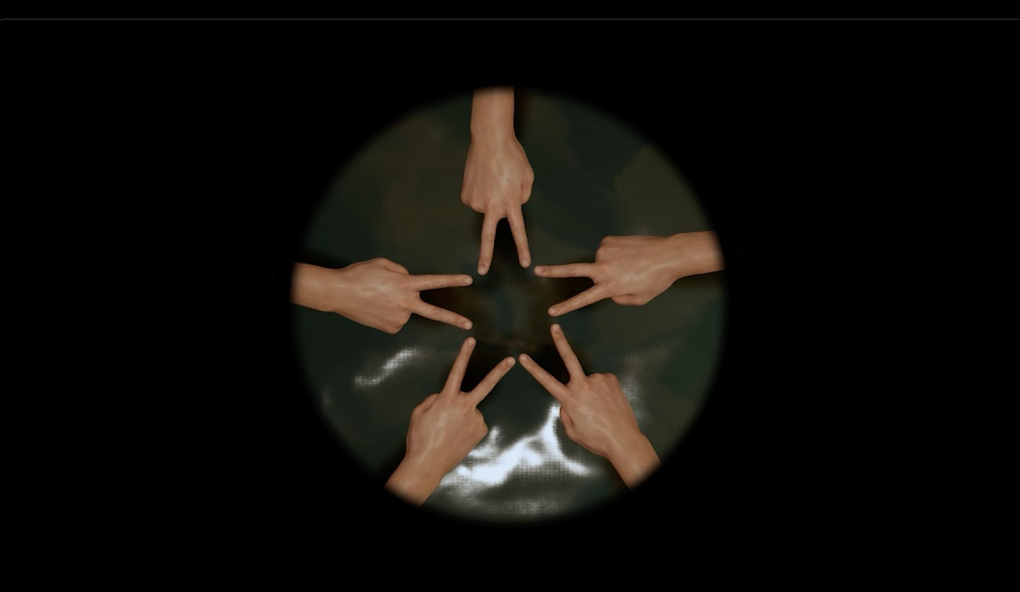

Susu’s work refrains from grafting answers to these questions. Rather, it is content to explore the materiality of these images on their own terms; a literal requiem for a dream. We could maybe call these emblematic images attached to the concept of country—maybe, tentatively—a nation’s collective memory. The stuff of propaganda and ideology, for sure. But with a slippery potential. Susu is preoccupied with that slippery potential, attempting to drag an impersonal imago down into the cosy recesses of the personal. Staking an intimate claim in a fuzzy public space. Imposing on the bullying indifference of history itself with the candid rose-tinted tenderness of a teenaged journal entry. And like a teenager’s journal, it is equally given to optimism and ennui, and even the odd power fantasy. In Remember To Dive 回溯潛水, the artist’s free-flowing visuals fleetingly arrange into discernible objects just once—oranges or tangerines, and then a configuration of linked hands forming a five-pointed star within a circle. A pentacle. As if to say, this deep field of feeling/fantasy/memory that the works intrude on and simulate is sacred, a space of ritual magic. Somewhere where a more ideal, home-like setting can be tinkered with and conjured—so like most journals, a space of thwarted longing and wish fulfilment.

Susu 蘇子誠, Love and Resurrection (detail) (2022), drawing on MDF, soft pastel, acrylic, pine. Image courtesy of Te Tuhi, Tāmaki Makaurau.

Tying the videos together and a more static capture of Susu’s thesis is Love and Resurrection (2022). It’s a pastel Rorschach drawing on MDF, aligning nicely with these themes of deeply personal memory, of the ways in which reality is internalised and claimed with roaming fantasy, and how fantasy can sometimes be powerless to reconcile its own diasporic fractures. If anything, it drives home the underlying impression from Coco and Aiai 可可愛愛 that memory is a pastoral practice, a garden whose flowers can be fed and watered, or left to wither, dependent on the intractable seasons of an inner life. For Susu the messaging is optimistic—within the frame is a flower in nearly-modernist fragmentation, but visible enough are its stamens and uterine pods. Resurrection indeed. Rebirth—and the fecundity of what we leave behind—is what’s on the artist’s mind here. Every flower in the oasis of memory is precious. In Coco, this digitally-rendered oasis has a coda that zooms out to tie previous scenes together on a heart-shaped island—sentimental, yes, but deliberately so. Aware of its own kitsch by design. Presumably because its own artifice is the point, perhaps asking if something is less beautiful for being synthetic (or even artificial). And maybe even probing further by implicitly suggesting there’s nothing on earth that isn’t synthetic, that purity is a dream, that borders are permeable and subsequently permeated because living systems cannot exist in a vacuum. One thing in an ecosystem affects another, and so on. By emphatically contrasting their video works with a more traditional medium, Susu also seems to say that no matter our methods, the cultivating of identity through memory is a simple mechanism unchanging through time. In the hybridity of the garden, everything is recorded for cross-pollination—fertiliser for the plurality of the universal archive.

Skin in craters like the moon was on view at Te Tuhi in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland from 24 February to 28 April 2024.