Sebastjan Brank: Could you describe DIZZY—the narrative, the technical aspects, the general mood of the film?

Juliet Carpenter: The film opens with an extreme close-up of a woman’s face, and slowly zooms out to reveal she is lying completely still on a bed in a messy, dimly lit bedroom. She abruptly begins to repeat a series of precise, mechanical movements. It’s not clear what the movements are for. Periodically, she takes trips down a staircase to a bassinet which has a baby inside, but it’s not a real baby, it’s a hyper-realistic doll. In another short sequence she is kind of dancing, writhing around the room.

These events are seen from several different camera perspectives—a more objective, classic camera; a baby monitor camera; a handy-cam; and the woman’s vision, which is very blurred and spherical. The film is about twelve minutes long.

Still from Juliet Carpenter, DIZZY (2022). Single-channel HD video, colour, sound. 11 min 53 sec.

SB: Does the character have a name?

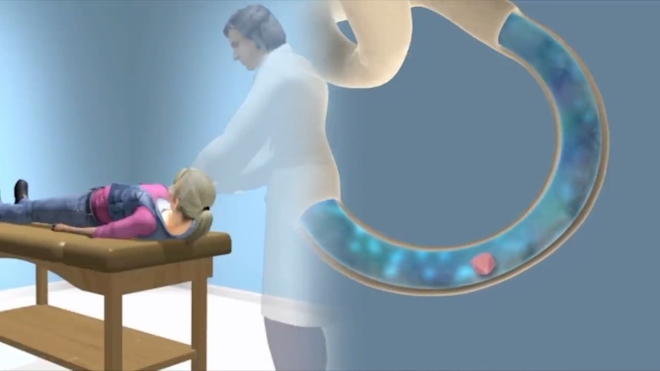

JC: In the screenplay, I wrote her name as Dizzy. The woman in the film is experiencing vertigo—thus, dizzy/dizziness. The sequence of movements she’s doing is called the Epley Manoeuvre, which is a medical manoeuvre that a doctor would prescribe to someone suffering from vertigo.

SB: The actress, Shade Théret, comes from a dance background, right? You can tell by the way she moves—the film is choreographed, in a way. Did you practise this with her?

JC: Yes. My preference was always to work with an actor, not a dancer. We asked everyone coming to the casting to prepare a dramatisation of the Epley Manoeuvre. Shade came and her rendition was just so good. I really enjoyed working with her. The ‘dance’ sequence where you hear Spinning Around by Kylie Minogue is all Shade’s choreography. We did several rehearsals before the shoot but there was a lot of improvisation that came in once we started filming. Shade was very confident and rigorous. I was worried about it looking too much like a dance film, but in the end, I think it’s the right balance.

SB: The house she lives in is a little grotesque. The signifier ‘home’ is usually associated with something cosy, intimate, pleasant. But in films, these spaces are often portrayed as alienating and uncanny—many horror and home invasion films exploit this sensibility. Can you talk about the house and the setting?

JC: Henry Davidson, the producer, found this location in Marzahn on the outskirts of Berlin. It’s a ferienhaus (holiday home). It did the exact thing that I wanted, which was to give a sense of alienation, somewhat like a hotel room—it’s not your home, but it’s meant to be for a short period. It was important that the house felt like a vortex—that this character only exists within this house, and nothing really exists beyond it. No one is coming to visit the house, or her.

SB: In the history of cinema there is this endless fascination with white female madness or insanity. One could trace a kind of genealogy of unhinged femmes on screen: Grey Gardens (2009), Repulsion (1965), What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962), A Woman Under the Influence (1974), Gaslight (1944)... You could call this trope misogynistic, but I think we can agree that you can’t just reduce it to that. Can you talk about this archetype and why you find it so fascinating?

JC I am a bit obsessed with films where women get completely dismantled or unhinged. I do think it is a misogynistic trope; but I think not being able to observe one’s own ambivalence towards such spectacle is shortsighted. Everyone, including women, has this desire to see feminine characters ruined. The Real Housewives (2006–) reality franchise is a good example of this. It represents the perfect kernel of contemporary contempt and salacious desire for the spectacle of a failed feminine subject.

When I started working on the film, I read Invention of Hysteria (1982) by Georges Didi-Huberman.(1) The book charts the co-emergence of photography and particular medical pathologies such as hysteria in a Parisian psychiatric hospital during the 19th century. In this particular hospital, inmates diagnosed as ‘hysterics’ were methodically photographed in bizarre, quite amazing mise-en-scènes. The choreography of the women in these images aimed to describe certain types of hysteria. There were also salons where the physicians would sit in a theatre, and women from the asylum were brought out to perform particular ailments. The patients who delivered the best performances were given special status and became imprisoned celebrities of sorts. Subjectivity was not only documented, but produced with and by the camera. The production of hysteria via moving image is still very present in filmmaking today.

Installation view of Juliet Carpenter, EM (2022), in Otherwise-image-worlds, Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, 2022. Photo by Sam Hartnett.

SB: It is interesting to reflect on the contemporary reception of Freud, who is often accused of pathologising hysteria, but who was probably the first to start listening to women instead of regarding them as crazy. According to him, it was hysteria that articulated the truth of the unconscious, and the ‘hysterics’—who admittedly were mostly women—let the unconscious speak through their symptoms. Later on, Jacques Lacan praised the hysterics for using language creatively, subverting more ordinary linguistic expressions. For Lacan, hysteria became not so much a behaviour but a psychic structure that leads the subject to question the role ascribed to them by society. In relation to hysteria, there is always this question mark.

JC: I’m interested in the ways hysteria behaves in different contexts—historically, medically, but also technologically. If you think about recurrent neural networks (RNNs)—a kind of technology used in recommendation engines which are what all mainstream social media are built upon—they behave in stereotypically hysterical ways: huge networks are designed to make associations between things that seemingly have nothing in common, and therefore can both target and produce subjectivities.

With DIZZY it was important for me that the film moved between different technological mechanisms, and ways that the character and the viewer is able to see. I like working with several different kinds of cameras. I’ve received criticism that it can be distracting. But for me, it’s more familiar to be switching between different qualities and types of visual stimuli.

SB: I don’t want to say ‘form follows function’, but did using different cameras and angles align with your exploration of what one could maybe call incoherent subjectivity?

JC: In order to describe a subject that is splintered, it doesn’t really make sense to use one super familiar camera. I think you can create an immersive, cinematic environment between lots of different looks.

SB: We are always permeated by external factors that we do not have complete control over, even if we constantly disavow it. The characters in your films embody this lack of mastery over oneself.

Still from Juliet Carpenter, DIZZY (2022). Single-channel HD video, colour, sound. 11 min 53 sec.

JC: I do not really believe in the liberal idea of a pure, authentic self. It’s not that people are incapable of being authentic, but in screenwriting, characters are often defined and predetermined by their core motivations, a kind of inner problem they have to solve. I am more interested in depicting conditions that are self-contradictory. The baby in the film is supposed to create this continuum of her subjectivity that spills outside of itself.

SB: The character is trying to get rid of her persistent vertigo via repetitive movements. When she finally succeeds, there is a brief moment of transcendence, or maybe happiness, but then it gets kind of grotesque and self-destructive again.

It’s funny that sometimes the best sedative for daily disorientation is even more disorientation. For example, going to a club and listening to unbearably loud music can lead to a sense of inner calm. This also got me thinking about the death drive and its many interpretations. Think of running a marathon—it is through repetition of physically strenuous movements that you reach a state of transcendence, a state beyond mere repetition. We feel most alive when we negate life itself.

JC: The whole film was based on repetition. You basically only see her do this one thing. The only thing that breaks this are her trips to this unusual doll at the bottom of the stairs. You could describe the musical sequence as the climax of the film, but I wasn’t trying to make it joyful or emancipatory. It’s meant to still be within the logic of this insane repetition. I think it’s as you describe it, in that the pursuit of pleasure always involves some sort of pain.

SB: If we go back to this brief moment of pure bliss or ecstasy, we can hear Kylie Minogue’s Spinning Around. Pop music can be a powerful vehicle for many things. What is your relationship to it?

JC: I just genuinely love pop music—the formulaic-ness, the way that it works is extremely manipulative and satisfying. I wanted pop music in the film, but I knew that it needed to have a level of uncertainty around the clarity of her euphoria. I’m not against using simple manipulative pleasures, because that’s how they work in the world—I feel affected by pop music.

SB There’s this quote by Annie Ernaux that a mutual friend of ours, Andrew, sent me: “A book offers more deliverance, more escape, more fulfilment of desire. In songs one remains locked in desire.”(2) I guess what she’s trying to say is that when you hear a pop song, it immediately throws you back into a moment. It’s very sticky and resilient.

JC Film is inherently such a bastard medium. I’m not a believer in the idea that you shouldn’t use things because they’re manipulative. If you think this, working as a filmmaker, you’re a bit delusional.

SB Maybe we can talk about the relations that Dizzy has with inanimate objects in the house. Somehow she’s libidinally invested in those objects—most notably, the creepy baby, which again reminded me of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? and Bette Davis’ baby form, her miniature replica of herself.

JC The idea for the baby didn’t start specifically about it being a baby. I knew that I wanted the main character to be alone, but I needed there to be another presence, something semi-sentient. I was like, is it a dead body? Is it a mannequin? Then I became fascinated with these reborn dolls. That’s a whole other thing to perhaps make a film about—the culture of people who collect these hyper-realistic dolls.

Once you put a woman and a baby in a room together, it immediately conveys the idea of motherhood. Although this wasn’t in the forefront of my mind, I accept that’s the symbolic relationship a lot of viewers interpret. For me, the character of Dizzy and the Doll are one and the same, and they create a closed circuit of subjectivity and madness. Dizzy herself looks a bit like a doll; she seems disaffected and mechanical in her movements. And the doll is immobile but looks very realistic. It’s been interesting to learn how heavy the symbols you work with can be. Some people interpreted this film to be about postnatal depression. I think that comes back to what we were saying about this ambiguously misogynistic trope.

Still from Juliet Carpenter, Deep Head Hanging Manoeuvre (2022). Animated video, sound. 2 min 35 sec.

SB: I’m a big fan of films taking place in enclosed spaces. I love a good chamber piece. It’s a powerful format, because I think stripped-down films can force the actors to be more inventive. They also confront us viewers, who are used to being constantly inundated with sensory stimuli, with the brutality of immobility as well as the fact that what we are usually most inconvenienced by is other people, to quote Lauren Berlant.(3)

JC: I also feel very drawn to the chamber piece. Right now, I want to be able to make works that are self-evident, immersive worlds of their own, whose rules are justified from within. To me, a way of getting to that is working with a discrete environment. I’m not against films that work in other ways—that’s just what I’m learning to do right now.

The exhibition Otherwise-image-worlds was on view at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery from 4 June to 4 September 2022. It was developed in partnership with Te Uru, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland and curated by Tendai Mutambu. Supported by Creative New Zealand Arts Council of New Zealand Toi Aotearoa.

Interview republished from the Otherwise Worlding reader, published by CIRCUIT Artist Moving Image (2023). Sebastjan Brank is a writer and cultural worker based in Berlin.