I’m wondering whether you might have watched Sean Grattan’s HADHAD before reading this essay. It’s rather daunting to provide an introduction in advance of viewing a time-based work of art, One reason is that while it’s interesting to have some initial context, it’s also very different from looking at a work “cold,” without previous assumptions, something even rarer with extremely well-known works as their reputations often precede them. Anticipation is one of the most interesting experiential phenomena when approaching any artwork for the first time so I don’t want to completely undermine that process. (I will venture that I have watched this video more than a few times now and it doesn’t suffer on repeated viewings, and perhaps only seems stranger.)

One is also disinclined to “spoil” the work, although while Sean Grattan’s video piece HADHAD has some of the creepy, thrilling, atmospheric qualities that draw us to popular entertainment, it is not as dependent upon a narrative structural framework. The work is often unsettling, but with top-notch indie production values, and an impressive, highly imaginative scope to its timely themes and concerns. The setting of the work involves both generic California landscape: the interior of a home (seemingly a cabin), and the wooded terrain familiar from exterior shots in many US television films.

We also encounter close-up shots of everyday objects and spaces but instead of being comforting and reassuring they become alien and defamiliarized. Especially in the case of food, which acts almost as another character in the video (gravy, mush, raw carrots, potatoes). And kitchenware, such as the rectangular plates, white coffee makers and toasters, rows of stools, bespeaking the average Briscoes or Pottery Barn chain averageness. The actors themselves inhabit a set characterized by its clean, bland surfaces and wear non-descript khakis, pastel shirts, brown loafers: shopping mall couture. (I recall the clothing brand Gap attempting to portray khaki slacks as arty/hip, their advertisements proclaiming: “Picasso wore khakis,” “Rauschenberg wore khakis.”) The set design and costuming appears moreover vaguely anachronistic without accurately conjuring a period piece; some “good old days” that never existed, a bit like the US brand “OLD NAVY,” its products bearing no relation to either word in its name.

HADHAD (2012) Sean Grattan

The dialogue employed in HADHAD is a heavily stylized, 21st Century Orwellian text-speak, almost robotically, unemotively recited. I hasten to add that this strikes me as a very difficult thing to do, and to do well. It also resembles the stark dialogue of independent filmmakers such as Hal Hartley, Jim Jarmusch, David Lynch, and Jane Campion. We encounter terse, confounding clusters of aphoristic statements, not unlike the business jargon of airplane paperbacks and corporate PR. In the future, the past won’t exist. The future-predictive ideology of technological singularity is alluded to throughout: the notion that at some point later in this century artificial intelligence will have spectacularly outshone our own.

When the time comes, will humans forget what it was like to die?/The end of death is a likely result of evolution. It is clear that once the exponential acceleration of artificial intelligence begins, the next modification of humanity will follow. This will happen via the metamorphosis of people into digital technology elements of this change are visible today. Though nothing can prepare us for what the future will bring!

Grattan presents us with a bracing artistic corrective to this prognosis here, with future prospects that are envisioned as mundane, ordinary, manifestly beige as our protagonists continue to recite monologues seemingly drugged, or half-asleep, tranquillised, nullified rather than emancipated by progress. There’s a weird blankness in their manneristic speech incorporating strange, euphemistic language, bug-eyed earnestness, and absence of irony. But the intonation of the actors’ voices rises at the end of each phrase, so that each sentence, declarative or not, becomes in effect a plaintive question. And the script takes many knowingly convoluted twists and turns in and out of philosophy, logic, and utopic prognostications. (And as a lecturer in art theory I have the distinct impression that Grattan has also spent heaps of time in seminar rooms and libraries as well.)

Although Grattan works in the studio of the LA artist Ryan Trecartin, his work is quite different in its more measured pace, style, and tone. Grattan has created a darkly perverse imagining that depicts more of a narrowing than awakening of unexplored human potential. If this sounds like it’s no fun at all, that’s absolutely not the case as it’s actually very witty, well-crafted, and weirdly enjoyable. Here’s where the peculiar artfulness of HADHAD comes in, this distorted parable that allows the viewer to trace their own thoughts around its complex, unlikely, and perverse surfaces. Moreover, the imagery of HADHAD operates along a wide spectrum between the generic and the specific, the former drawn from dystopian characterizations of the suburban wasteland and the latter a peculiarly hybridized amalgam of cultural references and New Age doubletalk. The motto of Google: “do no harm” despite the fact that so much of their technology derives from the military industrial complex is indirectly referenced in the following exchange:

It may be a fact that violence will become a plug-in like everything else. We only have to fear the sale of that data to a business with aspirations to dominate. However, Capitalism will rejuvenate itself from the inside out, resulting in the opposite of what Hannah Arendt described as totalitarianism: absolute free movement, a purely generative social organization of people. Ultimately, this will remove the need to use violence as a means to success.

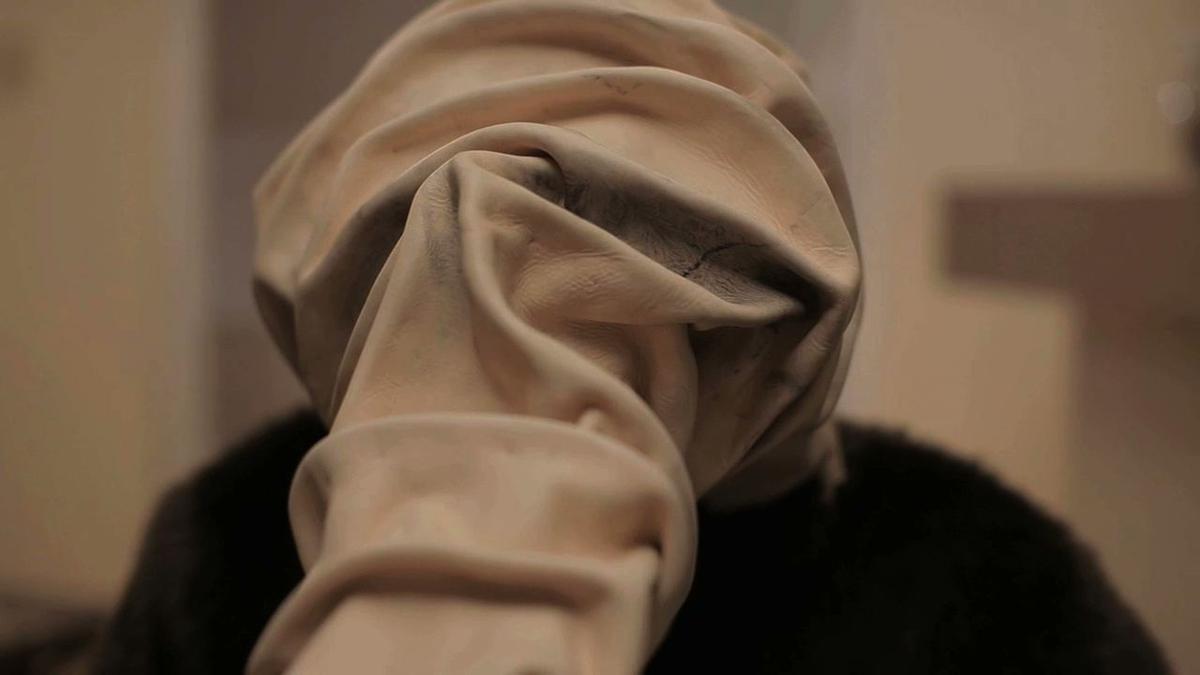

But the loose narrative seems to build towards and hinge upon (spoiler alert!) the appearance of an “unidentified visitor” in the midst of the five protagonists (three women, two men) we’ve been introduced to thus far in the video. This follows an after-dinner game entitled “cards of meaning and a hummed “celebration song.” Maybe it needs help./Let’s bring it inside. The “it” in question being a simian-like, furry creature with a featureless fabric head. This creature-apparition also recalls the Surrealistic films of Jean Cocteau and Luis Bunuel or Rene Magritte’s painting The Lovers, which features an embracing couple with shrouded visages. Or even the parable-like prehistoric sequence of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). The characters’ verbal reactions incorporate the a-typical sort of analyses we’ve encountered throughout HADHAD: The introduction of a new element into a constellation of previously existing elements only causes a disruption if the formula that describes the situation cannot account for the results. Yet further reactions include mimetic bodily responses to the “creature”: crouching positions, elbows bent and jutting out, knuckles laid flat, poised on furniture. And, in the end, a precarious, Asana-style pose. Did it just move?

Generally speaking, which is pretty hard to do about this video, one might offer that HADHAD burrows into, and revels in, the enormous paradoxical contrasts that emerge between an embodied “being in the world” and the dream/nightmare of a dis-embodied, entirely virtual state of existence. Smiles become grimaces, food becomes repulsive, language becomes incomprehensible. The creature that makes its appearance known “does not compute” in relation to the situation in which it arrives. This tension is made manifest both through dialogue and an increase in higher volume, Goth-ambient quotient of the soundtrack.

What I am doing right now does not make sense to me I believe that my actions are being controlled by a force that is outside of my body. [...] I am concerned that we do not know what to call it. And this uncertainty plants a seed of fear in me.

But finally, don’t be afraid, and do watch HADHAD. Even with its “scary” parts it’s not half as frightening as the world it’s responding to with utterly disarming accuracy.

Note: All italicized sections in body of the text are quotations from HADHAD.

The author would like to extend thanks to Shannon Te Ao and Nina Tonga for their co-curated exhibition Such A Damn Jam held at Massey University’s Engine Room gallery (17-26 Sept 2014), which initially brought Sean Grattan’s work to my attention, and of course to Mark Williams for posting Sean’s work on CIRCUIT.