In 2012 Dr May Adadol Ingawanij was the curator of the Bangkok Experimental Film Festival. On Friday Aug 30 she will be part in the CIRCUIT symposium Looking back into the Future, as a panelist in our Professional Practice Forum (morning) and later in the day presenting a screening of recent Asian experimental cinema Reuse, Retell. (Both at Elam School of Fine Arts). Ahead of May's visit we talked to her about Reuse, Retell and issues surrounding the distribution of Asian work.

Mark Williams (MW): Many of the films in Reuse, Retell re-work images from existing films. What makes them so ripe for revision?

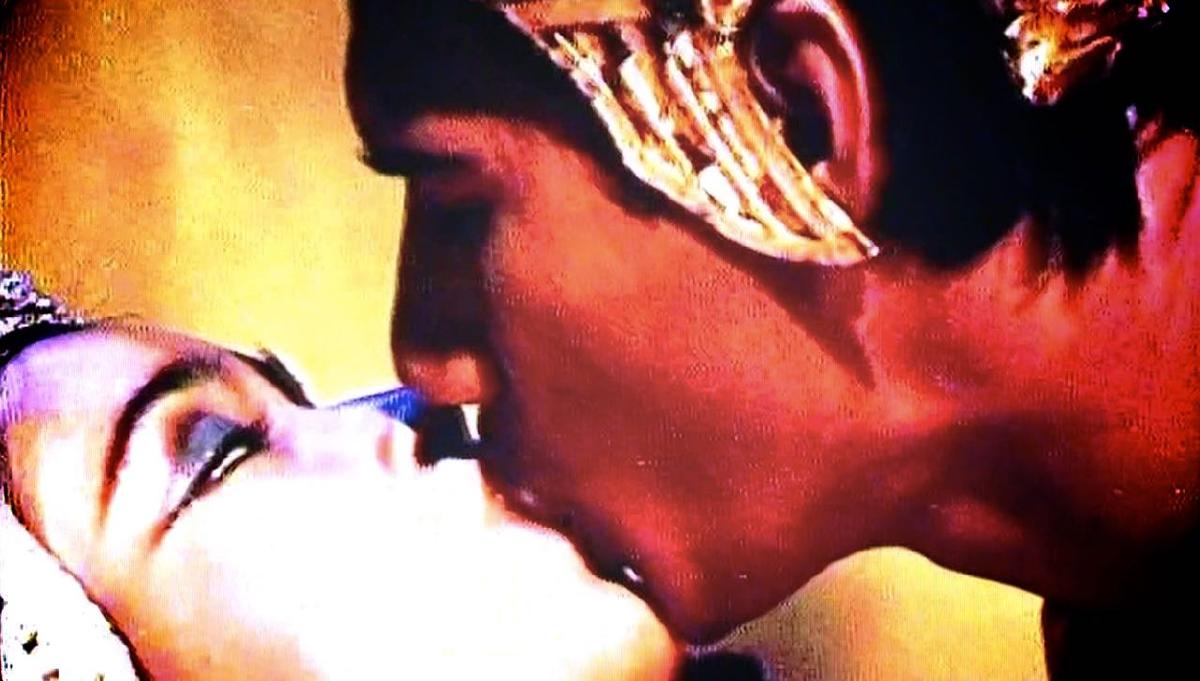

Dr May Adadol Ingawanij (MAI): I wanted this programme to play with the idea of the archival gesture, and the moving image as archive, in a few senses. The films that begin and end the programme, A Soldier’s Song Sample Experiment (Nyugen Trinh Thi) and Time of the Last Persecution (Taiki Sakpisit), re-edit feature films that would now be regarded as outmoded relics in Vietnam and Thailand respectively. Yet Thi and Taiki aren’t doing this out of a sense of nostalgia. Their films are very much anchored in the present. The intensity of each of their films evoke a conflicted present in the countries in which they’re made, a present in which the promises from the past haven’t been met and ghosts from past catastrophes have yet to be laid to rest.

Still from A Soldier’s Song (2011) Nguyen Trinh Thi (Vietnam)

Thi’s film and Hyewon Kwon’s Untitled #1 also exemplify a very interesting strategy of approaching old film footage as social archive, yet displacing their original intention in order to create subversive meanings. The film whose images Thi reuses is one among many state-sponsored feature films made as propaganda during the Vietnam War. The provenance of these films is an ambivalent one, yet it would be too easy to ignore or forget about these films now in the name of having "progressed" to a more peaceful time. A question that interests me is what can artists in the present do with archives and archival works whose points of origin are deeply problematic, and to what end do they do so?

The other sense of the archival that I wanted to show has more to do with a process of creating work through assemblage, drawing on a personal library comprising of found footage and that which the artist has shot and accumulated over time. This is a common departure point for many moving image artists in Asia and elsewhere. You see shades of this way of working in the films by Chulayarnnon Siriphol (A Brief History of Memory) and Tanatchai Bandasak (Air Cowboy), and the interesting question here is how the context, or the moment in which the film is being put together, shape the tone and texture of the work. In Chulayarnnon’s case the context is a very fraught moment in Thailand’s political life, an atmosphere in which no-one can avoid being affected by politics.

MW: In 2012 you curated the Bangkok Experimental Film Festival, where you showed some of the works in Reuse, Retell. What role does BEFF play in the wider Thai art or film calendar?

MAI: The first edition of BEFF took place in 1997 as a collaborative project led by the independent artist and curator-run initiative Project 304. There are now several good annual film festivals in Bangkok, and one-off moving image exhibition and installations take place on a regular basis in the city. BEFF remains a key crossover moving image event bridging the art scene and the independent film scene. We’re run on a voluntary basis, and on a very low budget scale, and so can’t afford to take place every year. But I think in many ways we also benefit from the luxury of being free from the annual calendar. BEFF takes place every couple of years. Each edition has a different curator who comes up with theme he or she wants to play around with, and shapes the direction of the festival accordingly. The identity of the festival changes each time depending on what each curator wishes each BEFF to be a site for. At its heart BEFF is a site for proposing, experimenting with, and exploring a set of questions and provocations arising at that particular moment of the festival’s life. The question of context, of a sense of urgency arising from engaging with the place in which this festival takes place, is never far away.

The other thing we prioritise is touring curated programmes after the Bangkok event. Much of artistic and cinematic practices in Thailand are highly Bangkok-centric and so we try to do as much touring as we can, largely to university campuses in regional cities. We also send programmes to international venues such as galleries, film festivals, or university campuses. The CIRCUIT screening at the University of Auckland is the second time we’ve had the pleasure of touring to New Zealand. What’s nice about showing BEFF programmes internationally is that we’re working with international collaborators on terms other than sending out screeners for institutionalised programmers or curators to select from for their events.

MW: Could you talk a little bit about the background of the film-makers in Reuse, Retell ? Do they have a formal background in art or film? Or are they self-taught?

MAI: Yes, most do, and in some cases via degree education abroad. I’m fascinated by the maker of the oldest film in this programme, which I discovered watching a programme of Indian experimental films curated by Shai Heredia of Experimenta festival in Bangalore, though I barely know anything about him. S.N.S Sastry’s And I Make Short Films was made in 1968 within India’s state-funded documentary production organisation called Films Division. This is fantastically surprising work coming out of an official documentary production unit! According to this MUBI post Sastry trained as a cinematographer in Bangalore, joined the Films Division as a cameraman, and started directing films from the 1950s.

_image_524.jpeg)

Still from And I Make Short Films (1968) S.N.S Sastry (India)

MW: Growing up in New Zealand in the pre-digital age there was very little distribution of experimental film, whether local or international. As someone of a similar generation, I'm curious what the situation was in Thailand?

MAI: A place showing experimental films as such didn’t exist when I was a teenager in Bangkok in the late 1980s… and I can’t resist adding that Thailand still doesn’t have a cinematheque. Video art was beginning to appear every now and then in a few galleries towards the end of that decade. A little later in the 1990s a cinephile and, at that time, film writer called Sonthaya Subyen, mounted an idealistic individual effort to regularly show what he called “overlooked” films in a bookshop. You can read more about him and the Filmvirus initiative he set up in a piece I wrote a few years back.

It came to me, thinking about your question, that the youth of my generation in Thailand would have been indirectly exposed to experimental touches in moving image through music videos and advertising. Things from MTV were shown on a few of the pop music programmes on TV, which we watched religiously—music videos and Converse trainers were the mark of modernity for our generation. Video rental shops had music video tapes you could rent, recorded unlicensed from satellite TV and probably also by people who were studying in the US or Europe. I spent part of my childhood in London in the mid-1980s. There was one time we had a houseguest from Bangkok who had friends working in advertising. He was instructed by them to record as many ad breaks as he could from TV during the time he was in London!

MW: In 2009 you wrote the catalogue for Unreal Asia, a collection of Asian moving image work at the Oberhausen Film Festival. What are the challenges of showing Thai or Asian work in a Western context?

MAI: Probably not a million miles from the dilemmas of showing New Zealand work in a place where you know people aren’t going to know so much about New Zealand. How do you curate and introduce works in such a way as to give a flavour of the context, histories, landscapes, places, and tensions that the artists are responding to and engaging with, yet without closing down the meaning of the works or turning them into illustrations of a national or regional entity?

A good example here is the filmmaker and artist you mention in your next question, Apichatpong Weerasethakul. He’s said many times that he can’t imagine making films and art outside Thailand—the everyday life, the conflicts, violence, and historical erasures specific to that place are sources of inspiration and motivation for him. And you can see that since the coup in 2006 and the political crises and murders that have followed, there’s been a sharper and more evident return to the unfinished histories of that particular place in his aesthetics. Yet it would be very unsatisfactory to conflate talking about Apichatpong’s work entirely with talking about Thailand, as unsatisfactory as talking about his work in order to talk abstractly about existentialism, death, Buddhism, contemporary art films, the philosophical turn in film studies or whatever.

It’s a good dilemma to have to live with though. The task is to find a way of showing works so that people can make unexpected connections, and which undermine clichéd notions about a place or an artist’s mode of aesthetic formation in some ways. Similarly, I think it’s a very productive exercise every now and then to juxtapose art and film works made in Asia—but in order to defamiliarise them through comparison. The point isn’t to demonstrate the Asian in Asia, that doesn’t exist, or it only exists as a fiction dreamt up by whatever state currently has the ambition to rise in the world partly by styling themselves as Asia’s leader.

MW: Apichatpong Weerasethakul is probably the most well known Thai film-maker internationally, winning the Palme D'Or for Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives in 2010. What kind of presence does his work have in Thailand?

MAI: He struggles to get his films widely shown in Thailand, and for that I blame the timidity of commercial cinema chains and the lack of astuteness and vision of official art and cultural institutions in Thailand. Uncle Boonmee was the first of his feature films to have received a commercial run in Thailand, and largely because it won the Palme d’or. But even then it was programmed in very few screens in Bangkok (which, by the way, were well attended and shows that people are hungry to see his work on the big screen in his country). After that it went to a few screens outside Bangkok, but not anything like the scale of distribution it should have got. His installations are occasionally shown in Bangkok, but again there are no cultural institutional will or commercial acumen to get them travelling domestically.

Apichatpong’s a huge inspiration for independent-minded filmmakers and artists in Thailand, and a great mentor to many of them. He’s also had to wear the activist hat every now and then especially around the issue of film censorship.