In she feeds the birds (2023) by Lily Worrall, the city is a palimpsest—a living archive that the titular character anxiously stumbles through in a fearful daze—catching glimpses of a bygone metropolis. In a montage of black and white photographs, we see Tāmaki under dystopian avian rule—the human population has been banished to the city outskirts to scavenge and appease their airborne masters. It is in the ruins and detritus of our city—layers of patchy asphalt, leaky car parks that arose from the dust of the demolition ball, and the reflective glass of high-rises making mercurial liquid of their surroundings—that a utopian longing emerges.

Lily Worrall, she feeds the birds (2023)

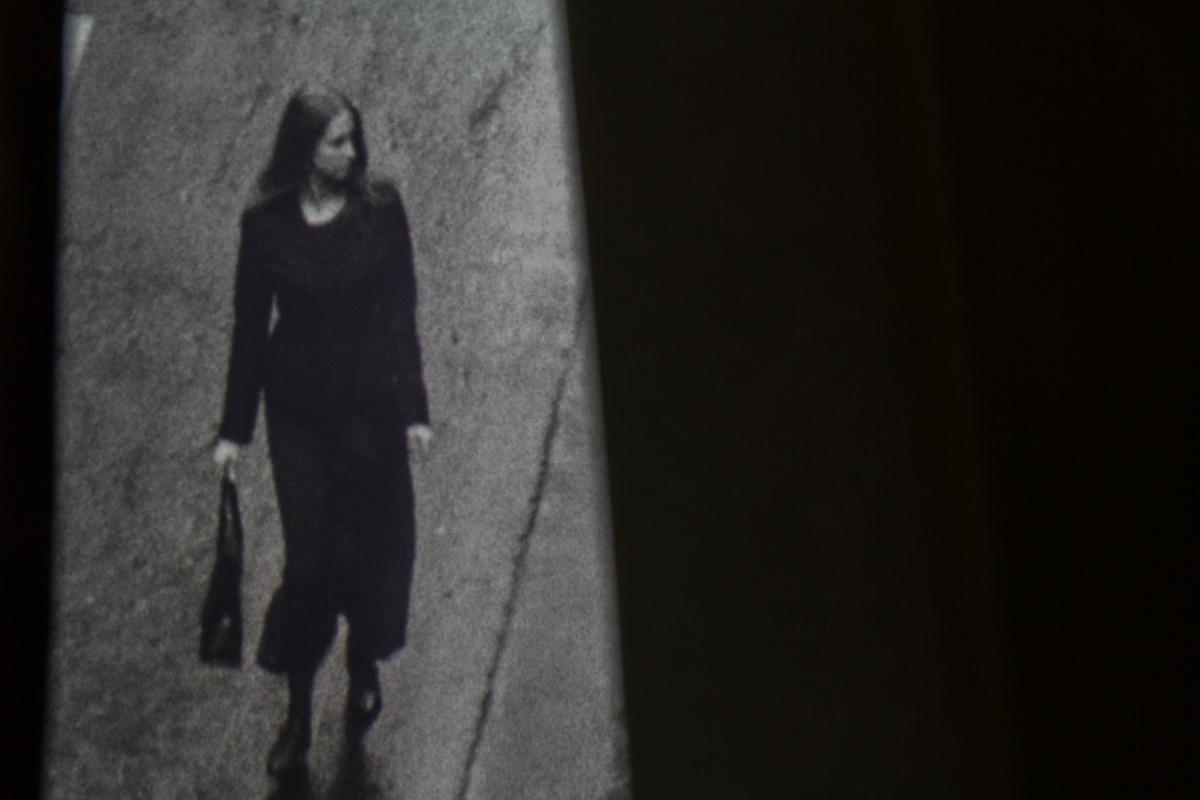

The film begins with hot second flashes: gulls loom above, frozen, but encroaching with each millisecond, scaly legs and hooked beaks protruding. Pause. We are inside somewhere: worm-riddled wood layered in peeling paint, a seat corner, white plastic chairs, a shadowy figure with long hair, hands covering her face. A silver token with a fish carcass enables an exchange to take place. Fingernails picked. PICK UP ORDER. Reflective surfaces: a gull in the corner. She walks, a paper-wrapped package in hand. In a balletic montage, she unwraps the package. Hot chips become fingers become the bony beaks of the gulls. In the theatre of the sky, a primordial feeding session takes place alongside the sound of thumping wings and squawks. What if birds aren’t screaming, they’re crying?(1) We all know of the battle waged between human and gull, having engaged in the pleasure of unwrapping oily paper to reveal steaming chips, burning the tips of one’s fingers in impatience. At the crackle of the paper, these rats of the sky descend in a swarm, lashing out at those that dare come too close. In our age of human primacy, though, this battle is largely one-sided. We shoo them away, or flick a lone chip to the wind as a token of pity. Most often, the bird has to scavenge through the paper discarded in the bin, or peck at the ground in search of golden crumbs. In she feeds the birds, this archetype is reversed. The hot, glistening package belongs to the birds, while the human is the vehicle through which they are served. In a moment of brazen desire, she steals a chip for herself. As it crosses her lips, chaos ensues. A beady, cruel gaze has noticed this transgression. Avian bodies take to the sky, menacingly—a dance of eye-contact ensues—and she runs.

She’s running, she ran, she will run.

Lily Worrall, she feeds the birds (2023)

Lily Worrall, she feeds the birds (2023)

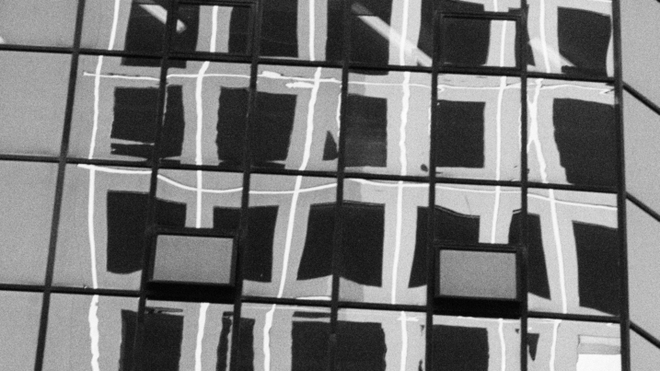

Enter the city. We first encounter it from the outside, a grainy vista to the soaring silhouettes of the gulls. In she feeds the birds, the city’s edges are where the humans live, the centre barren, left to the rule of the birds. In one corner of the screen we see The Grey Lady—the sky-puncturing concrete tower—hemmed in by glazed skyscrapers, luxury apartments, and shopping complexes. An allegory exists here: priced out of the city, affordable housing is only to be found, if at all, at the extreme edges. The polis itself is undergoing constant sanitisation—Commercial Bay-isation—a municipal effort to make the city centre a homogenised haven for the middle and upper classes, with a service kink for the Tourist. The result is an increasingly financialised cityscape where multinationals sell their polyester scraps, tourist shops hawk their shitty wares, boarded shopfronts flash their To Rent signs, the ever-increasing homeless population wander about in giant polyfleece blankets, and a population of ravenous gulls, sparrows and pigeons stalk the streets. To see Tāmaki continue its slow atrophy under our supposedly most left-wing government in decades harkens back to the era of Rogernomics, a period of free-market reform under Labour, which saw the gap between poor and rich widen, and a greed and gluttony that crashed catastrophically, leaving a wound on Auckland that still oozes. This is the wound that Worrall traces in she feeds the birds, the pus of this era the tissue of the film: the public cultural venues and heritage buildings, once the contact point for all sorts of Aucklanders, speculated upon and bulldozed in the 80s, sites of a cinema industry that flourished, and a fashion industry that now chokes along, never as it once was.

Lily Worrall, she feeds the birds (2023)

Like any piece of dystopian art worth its salt, it is when one begins to speak of the end that a description of a beginning can emerge.(2) In this avian dystopia, the beginning, in an ode to Walter Benjamin, is the cultural detritus of the city. From the leaky car park that stands directly opposite His Majesty’s Theatre—which used to bring in the suburban crowds and house an arcade filled with artist studios and community cultural venues—the dusty windows of a historic fashion-house, to the film locations of independent 80s cinema, she feeds the birds presents the spleen of Auckland. In the Baudelarian sense, the spleen is used as a metaphor to describe fragmentation: as something that "disrupts and posits itself as the opposite of time idealised, the idéal, blocking a smooth and direct return to the past."(3) The spleen has a deep yearning to make the "absent present again," and a love for that which has lost its "objective significance."(4) Through exploring Tāmaki’s spleen, the city reveals itself, bearing hidden and repressed spatial formations, which Worrall's character walks through in the manner of a flâneuse. Referencing Benjamin’s idea of "botanising the asphalt," Worrall’s character takes the city and the urban abject as her site of study. She is at odds with this psychologically and physically alienating environment, a dystopia, or, a city in grips of speculative financialisation. Entering the CBD now is an exercise of extreme misery. When I visited Queen Street last summer, for the first time since I left in 2019 and post-pandemic, my stomach coiled in disbelief. No longer does the CBD glint with the promises of a small-scale metropolis that I hankered to visit as a teenager, skipping school to catch the bus into the city. Instead it feels like the last beats of a heart, barely surviving on its failing pacemaker. Signs of care and investment are seen in bike lanes, plant boxes, and more multinational storefronts. It’s money spent on making CGI-visions and a pedestrian-friendly CBD, without thinking why one would want to walk there in the first place. Worrall’s film takes a bird’s-eye view of this slow decay, layering references to a moment in Tāmaki’s past where a better future seemed just around the corner.

Lily Worrall, she feeds the birds (2023)

In its stitched together photographic montage, she feeds the birds is a city symphony à la Dziga Vertov’s A Man With A Movie Camera, but rather than a dazzling portrayal of a city full of life and revolutionary potential, it is a city in ruins. Far from being nihilistic, it is these ruins, as Benjamin so adamantly argued, that present future potential. I’m reminded of the nihilism I felt as a teen when, self-important and affected, Aotearoa felt like the cultural boondocks to me, barren and artless. A weak simulation of a thriving metropolis with Culture™. These enthusiastic complaints were more indicative of my own ignorance, and it was only in my twenties that I came to find and appreciate the wealth and specificity of Aotearoa’s cultural heritage, particularly our film history. I had always sneered at the cinematic climate of Aotearoa, which appeared to me back then as a model of second-rate and insecure ‘pick me’ Anglo movie-making. We were desperate to please and willing to sacrifice all local vernacular and talent to host Big Cinema™, to the point of banning our film industry unions and funnelling all funding into enticing global studios to grace us with their visions, so unconfident we were in our own.

Lily Worrall, she feeds the birds (2023)

Upon learning about the cinema heritage of Aotearoa, I was humbled but also shocked, asking myself—how did we get here? The 70s and 80s were a golden age for cinema, where the uniqueness of the locality and history of Aotearoa could manifest through independent, transgressive film. Partly through the creation of the New Zealand Film Commission in 1978, and the early 1980s tax shelter opportunities, which attracted significant investment, a wave of films were made which, nowadays, would be near impossible to get funding for. It is this cinematic heritage that Worrall lovingly explores, with a particular focus on the aesthetics and discourses of the NZ Gothic and 'cinema of unease' that emerged in the 80s and 90s. She playfully riffs on the rhetoric and tropes that emerged in this era of movie-making: the solitary Pākeha man battling his seemingly adverse environment—the protagonist of pioneer culture and lynchpin of colonial settler identity—is taken one step further with the addition of his female counterpart: the isolated and neurotic Pākehā woman, the heroine of the NZ Gothic, who "exists only in the shadowy peripheries of society."(5) Worrall’s character traverses the sets of these films, fleeing up the very same Exchange Street spiral staircase which The Woman runs down in Angel Mine. With loving nods to Agnes Varda’s city-dwelling women, who are able to transcend the feminine masquerade to full subject status through walking and observing the city around them, Worrall’s character—in a dystopian city sans human life, senses a past that shrieks to be heard.

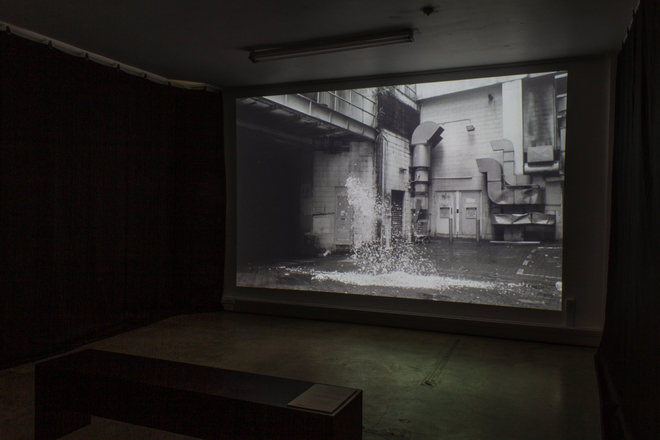

Lily Worrall, she feeds the birds (2023). Installation view, RM Gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau, 2023. Image by Ardit Hoxha.

Like Benjamin, whose interest in fashion as a form through which to analyse and understand capitalist modernity—both a commodity fetish and the process by which the new is eternally recurring, and therefore the site of possible redemptive and utopian elements—Worrall’s work is brimming with affectionately rendered references to New Zealand's fashion history.(6) From the fragmented close-ups of the protagonist's outfit, to the chattering of sewing machines, fashion is present throughout the film. Head-to-toe black, the character’s outfit and shoes are archival Zambesi and Minnie Cooper: giants of Kiwi fashion, which like many local fashion brands, have seen hard times in the last decades as brick-and-mortar retail struggles against the behemoth of online fast fashion. In a well-tailored Zambesi jacket, signature Zambesi bag, and Minnie Cooper shoes, the character is the picture of the NZ Gothic. Like its cinematic counterpart, the NZ Gothic as it manifests in fashion is a vernacular, romantic, and melancholic style that blossomed in the late 80s and 90s, and brings together well-tailored, locally made garments, often in black and neutral tones, to plays with deconstruction, surface, texture, and layering.

Over the decades, these aesthetics have been endlessly reiterated and replayed by contemporary fashion designers: though the garments produced are often platitudinous and cut-rate effigies to a bygone era. Having sacrificed expert craftsmanship, high-quality fabrics, and fastidious attention to tailoring, what passes for NZ Gothic in fashion these days is essentially variations on a black sack. I still love these sacks; they are staples in my wardrobe. I also don’t blame the designers, but rather the material conditions which have made it no longer feasible to produce garments in the same way as forty years ago. This loss of possibility is hinted at not only through costume, but by place. In the character’s nervous dash through the city, she stops for a moment of contemplation, acknowledging her reflection in a dusty window to the sound of sewing machines and chatting. She catches sight of a gull in this Kingston Street window, which once belonged to the seminal fashion house El Jay, the life and work of Gus Fisher. A figure crucial in the establishment of Aotearoa’s fashion industry, El Jay was the local agent for Dior—producing and selling in Aotearoa the multinational fashion house’s clothing. Now it’s boarded up and empty, with scrawls of illegible text traced into the grimey glass. We hear the whirring of ghostly labour and a bird call. She runs.

Lily Worrall, she feeds the birds (2023)

The character ends up in a concrete lot, air vents and patched asphalt surround her. She stands a stone’s throw from the site of His Majesty’s Theatre—an icon of Auckland’s cultural heritage— which, after years of intentional neglect, was demolished in the 80s wrecking ball boom. As the character looks around, seemingly haunted by the presence of this venue, though all the while surveilling the sky and the tops of the buildings for her avian overlords, the first hint of a piece of music emerges in the soundscape. Until this moment, the photographic flashes have been accompanied by a soundtrack dominated by a voice-over that echoes the mannered explanatory tone of public radio, airily but anxiously providing a live commentary on the film’s narrative, pierced by the cries of ship horns, sea birds, and the crackling of a dodgy radio channel.

Now, a repetitive riff begins to emerge, increasing in pace and volume. It is the soundtrack to Vince Carmen’s impaling act, the magician who performed as His Majesty’s Theatre’s closing act. As it plays, the character disappears, evaporating into a whirlwind of feathers, gently caressed by the warm air of the parking lot’s air ducts. This total transformation hints at a total beginning. Her quest through the city is a pile-up of the past and present, creating a montage of 'dialectical images'—Benjamin’s idea of an aesthetic standstill where different temporalities come together in a historical constellation—and that brings forth moments of reawakening and potential redemption hidden in the fragments of our city and its recent cultural heritage.(7) Worrall’s work is an archeological dig into the history that hovers just behind us, close enough that we feel its tickling breath and raspy whispers on our neck.

Lily Worrall, she feeds the birds (2023). Installation view, RM Gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau, 2023. Image by Ardit Hoxha.

It remains unclear what the fate of the human underclass is in the film. Is it through her desire to attend to and consequently understand her social position that she transforms into featherdown? Or is this the moment of rupture when, through her walking and seeing, she loses herself, subconsciously dredging up the city and its past, to become porous with her surroundings—a critical agent of history? Either way, it is in this moment of magic that she joins the gazers—those who have watched Tāmaki through a panoramic, tetrachromatic vista, safeguarded by their third eyelid—a translucent membrane that protects sight whilst enabling unwavering observation. Through her desire to see more and more, she becomes a bird, now fated to hover: a vigilant, attentive presence over Tāmaki.

she feeds the birds by Lily Worrall was on view at RM Gallery in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland from 5 to 29 July 2023.

Lila Bullen-Smith is an artistic researcher from Aotearoa currently based in Amsterdam. She holds an MFA from the Sandberg Instituut's moving image program 'Resolution', and is a practicing artist in the collective Brackish. From 2017-2019 she was a collective member of RM Gallery, establishing the RM Women's Moving Image Grant and Archive Project.