In 2009 Clemens Von Wedemeyer was commissioned by the Barbican Centre in London to produce what is an ostensibly impressive filmic exploration of themes of so-called "First Contact" and associated media representation.

Despite the intentions behind the Barbican commission, Von Wedermeyer decided that The Fourth Wall would not be "site specific."(1) The show has subsequently travelled to Dublin, Berlin, Paris and, most recently, to St Paul Street Gallery in Auckland and the Dunedin Public Art Gallery suggesting that the show has been packaged for an international, even if decidedly Western, audience.

Whilst obviously citing the theatrical notion of the "fourth wall" separating audience and performer (or performance from non-performance), the show also references the kind of ethnographic tropes which multi-national media conglomerates regularly transport from one market to another. This kind of "objectual" consistency (possibly more reminiscent of the natural and social history museum than the art gallery as such) delivers a familiarly ubiquitous product with clear narrative readability which tends to remain slightly alienating in its "spectacular" structure.

On the surface (and it may well be all surface) The Fourth Wall tells the now almost forgotten story of the Tasaday controversy. In 1971 a group of 26 "Stone Age" people were discovered living in a cave in the rainforest on a remote island in the Phillipines where they came under the protection of an eccentric millionaire with close links to the Marcos regime.

The Tasaday attracted immediate public interest, providing a modern audience with an example of "authentic" primitive humanity; a pure "first contact", a "state of nature" which contemporary human sciences could previously have only dreamed of or conjured up.

Contact was quickly seen to be destructive and, apparently protected from modernity's destructive forces by enforced isolation, the Tasaday were sent back into the rainforest home and receded and from public view. In the 1980s they were rediscovered by a Swiss Ethnologgist Oswald Iten who found them wearing jeans, living in houses and smoking cigarettes. A still unresolved controversy then erupted when he published an article claiming their 1971 discovery to be a "stone-age hoax."

Von Wedemeyer's presentation of this narrative is expansive and archival, almost forensic.

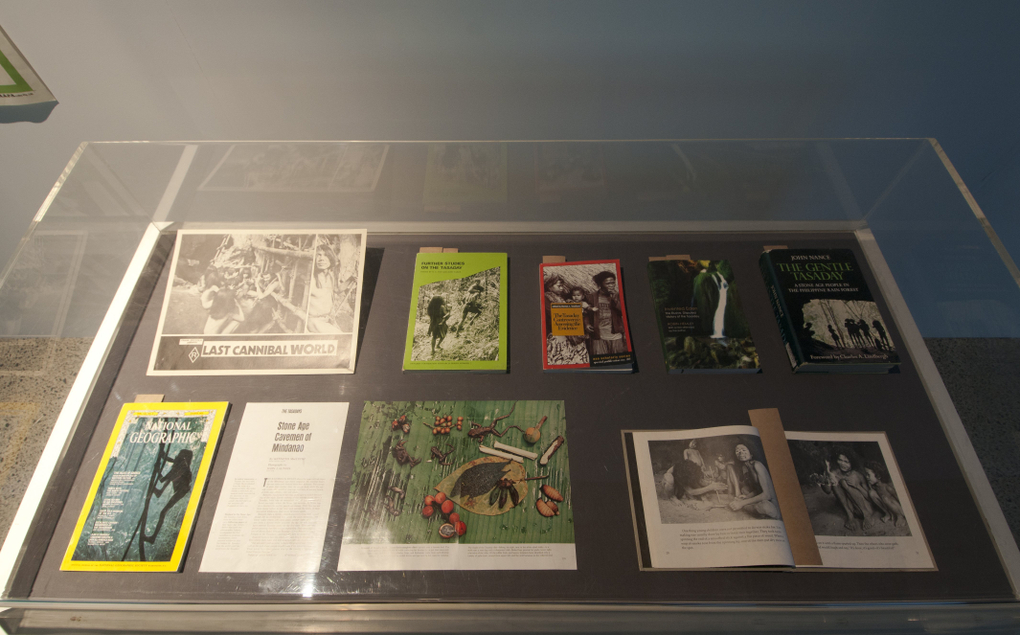

A wealth of carefully selected background material is provided: a "newspaper" (edited by the artist in collaboration with Paolo Caffoni), a vitrine of printed matter, a Wikipedia "track changes" transcript printed in the style of an info board in a natural history museum, and other ephemera.

Installation view of The Fourth Wall (2009) Clemens von Wedemeyer. Courtesy of St Paul St Gallery

Three LCD screens with headphones show video interviews with some of the key figures: John Nance, whose Message from the Stone Age (1983) was the first filmic documentary of the "first contact", Ruggero Deodato, director of Last Cannibal World (1977) inspired by the Tasaday story and inspiration to The Blair Witch Project (1999), and Geoffry Frand, an ethnologist who advocated a policy of "no contact."

The greater part of the installation is, however, dominated by five variously sized projections. Each offers noticeable material differences.

An "introduction" shows images of London actors dressed as "tribespeople" and is somewhat nostalgically projected in 16mm film. "Found footage" in low definition is projected on an adjacent wall, whilst a much larger pixelated projection shows presumedly objectified rainforests seen from a distance.

The last two projections are housed in their own rooms, cut off from the rest of the show by heavy black curtains. The first is an ostentatious, almost overproduced 35mm piece (converted to HD for exhibition purposes) which tells the story of a young man who talks with an ethnologist about meeting a lost tribe and being ritualistically granted immortality. The looped work finishes and restarts with the young man's self-immolation and implied resurrection. A final projection explores the theatrical notion of the "fourth wall" through the filmed performance of a group of actors "playing native" in the Barbican Centre Auditorium.

Installation view of The Fourth Wall (2009) Clemens von Wedemeyer. Courtesy of St Paul St Gallery

All up, there is some 217 minutes of video and film footage which is supplemented by an extensive amount of printed matter. While it remains unlikely that visitors will watch, read and absorb all of the material on display in The Fourth Wall, however one negotiates the material there remains a very clear, perhaps even over-determined and didactic trajectory through the installation.

Each of the elements—be they moving images, printed or internet matter—forces a reflection upon the very role of mediation in presenting or distorting the "truth". How does "documentary film," for example, construct or distort the truth? How do the conventions of theatrical presentation and its fourth wall create meanings and truths? How does Wikipedia's collaborative production or a newspaper's editorial structure inflect the facts or cynically posit a hoax? Where does acting begin and documentary end? Were the Tasaday real?

Von Wedemeyer may well leave us in a state of ambivalence over whether the Tasaday were a hoax or not, he may well play reflexive games over his own contributions to the constructions of stories, but we certainly find ourselves squarely placed within a discourse where truth, fiction and a decision between them is fundamental even if difficult. This didacticism may not necessarily be a problem—audiences seem to have enjoyed disentangling Von Wedemeyer's woof and weft of truth and fiction. However there remains another riddle which The Fourth Wall poses—or better yet, there may well be a fourth dimension breaking through that "fourth wall" and its puzzlingly simplistic epistemological dialectic.

In the most notorious essay on the relation between truth, fiction and its transformation in postmodernity (Baudrillard's art school staple, The Precession of Simulacra), sits possibly the most famous and certainly the most widely read reference to the Tasaday: Baudrillard devotes an entire section to the "lost tribe", reading their "first contact" story and the Filipino government's desire to return them to their original state as "a perfect alibi, an eternal guarantee"(2) of the very existence of a "real", "natural", or "pure" reference.

Expanding his critique to address the museological complicity in this construction, he adds: "The museum, instead of being circumscribed as a geometric site, is everywhere now, like a dimension of life. Thus ethnology, rather than circumscribing itself as an objective science, will today, liberated from its object, be applied to all living things and make itself invisible, like an omnipresent fourth dimension, that of the simulacrum. We are all Tasadays, Indians who have again become what they were—simulacral Indians..."(3)

Amongst the vast resources and reference material supplied in The Fourth Wall, this key work is conspicuous by its absence. While Von Wedemeyer draws us down an interpretative path asking us to decide on truth and fiction (or oscillate between them), Baudrillard sits outside the fourth wall telling us that truth and falsity do not matter, that as far as simulation is concerned we play a non-epistemological game of EFFECTS without causes, without truths or fictions as such.

At that point, the didacticism of The Fourth Wall begins to look more like the manipulation and simulation of the Fourth Dimension and Von Wedemeyer's apparent epistemological reflections begin to look like a post-post-modern "return of the repressed"—are we really being asked to reflect on truth and fiction in the absence of simulation? In this context I was left wondering how contemporary art is going to deal with the "recession" of the simulacra and what might be at stake in doing so.