At THE HIVE HUMS WITH MANY MINDS - Part Two at Silo 6 in Wynyard Quarter, visitors encounter nine further reflections on the networked contents of our urban and globalised world. While Part One of this exhibition included works that addressed the impacts of globalisation at the cultural or environmental level, many of the artists in Part Two take a broader view of civilisation, with works by Suji Park, Reuben Moss, Joanna Langford, Miranda Bellamy and Shahriar Asdollah-Zadeh looking at the technological or industrial effects of our age.

The difference between this iteration of THE HIVE HUMS WITH MANY MINDS and it’s predecessor at Te Tuhi is underscored by the choice of the waterfront silos for Part Two, which brings the exhibition out of the gallery and into site-specific space. Originally built to hold tonnes upon tonnes of Golden Bay Cement, the 1960s silos act as a formal negative to a significant portion of the material that built modern-day Auckland. Likewise, the former ‘tank farm’ sits on a large section of reclaimed land, created for the development of port and industry for European settlement from the 1840s onwards.

In the first silo, Mark Schroder’s The new modern efficiency is a fabricated retail lobby space created from various salvaged materials. Using a postmodern sculptural approach similar to the way painting, decor and object are formally interchangeable in the work of NZ/USA artist Martin Basher, Schroder repurposes visibly worn materials in a makeshift design derivative of retail shops, showrooms or displays at conventions—except grimier. Planter boxes that are a patchwork of used cinder blocks sprout tall dead weeds and stubbed out cigarette butts. A steel partition appears partially complete and semi-operational with sheets of recycled plywood, corrugated iron, fluorescent light fixtures, and old beach towels crowded onto a bathroom rack. In the seating area behind, a tropical beach scene of Youtube quality loops on a monitor, and beyond that, people are visible walking in and out of the silo doors. Around the corner, similar video content is deployed as visual filler on a couple of monitors where the gallery attendant serves free coffee at a makeshift reception area. The installation has no focal point and the visual pieces speak a formal language to each other that is purely decorative; yet Schroder’s grimy repurposing of the space feels functional, enjoyable even, implying that we are so familiar with postmodern retail-esque branding, with its emphasis on selling an experience, as a consumer it’s possible to not notice or even care what the product may be, or which object may represent it.

Installation view of The new modern efficiency (2016) Mark Schroder. Photo by Sam Hartnett

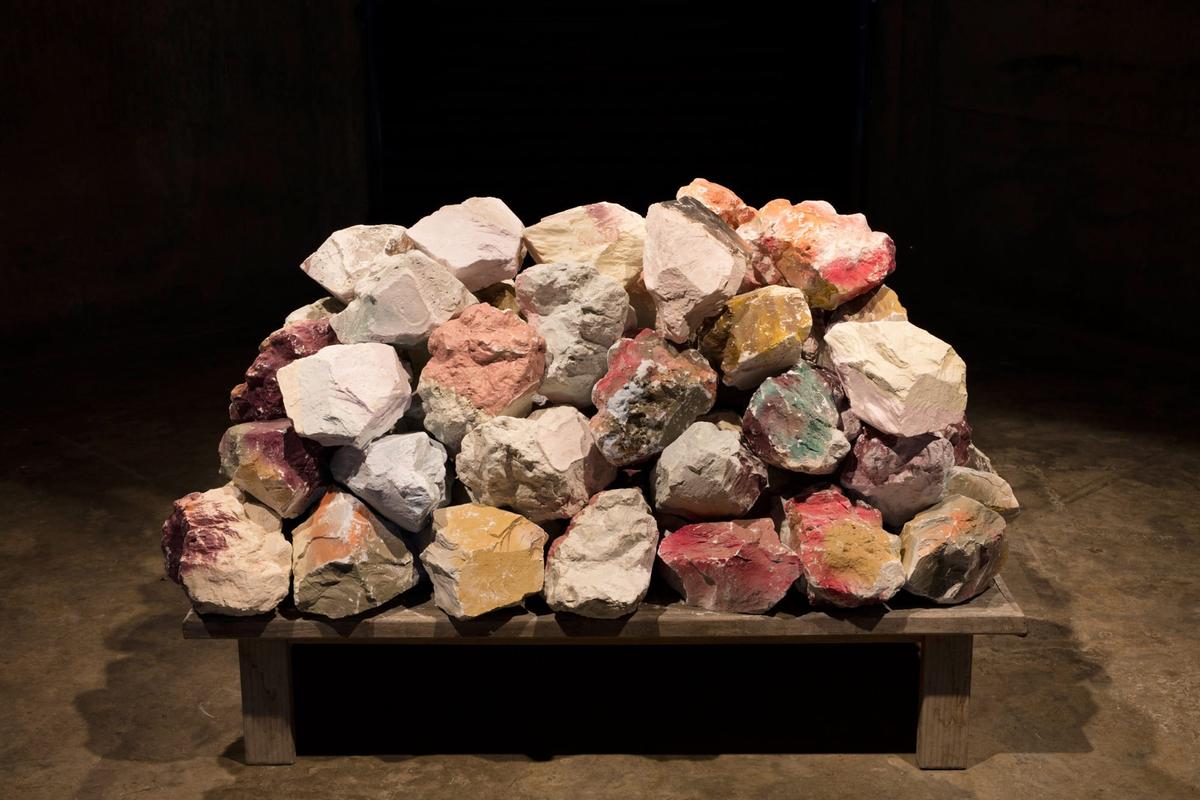

Positioned beneath a cement hopper in the next silo is Dols by Suji Park. A heap of large artificial rocks looking like candy-coloured scoria are stacked on a coffee table. These colourful plaster fakes have been buried and dug up again, giving them a suitably eroded look. It’s tempting to want to see the pile grow into a greater one, filling the size of the space they’re in, however the visual clue of the coffee table as plinth implies that its more important to see the rocks as stand-ins for products of culture, not nature. Indeed, under warm spotlights the rocks glow like a museum display from the future. Park’s Dols mimic the materiality of the newly discovered Plastiglomerate—a type of hybrid “rock” made up of ocean-deposited plastic trash and natural sediments—which, given the right volcanic conditions, will fossilise to leave their mark on the geological record as a form of man-made waste.

Creating an atmospheric backdrop, the deep, synthesised chords of Bellamy’s video Avail emanate from the space behind Reuben Moss’s Simulations: flood 2007-16 in the central silos. Simulations presents two six-metre billboards of two virtual cities, each a 500 block grid steeply tilting towards the viewer. The grid is a simulated city network of densely packed urban and industrial infrastructure—roads, factories, hospitals, schools, power plants encircling a great number of high-rises. The image has been built with SimCity 2000, an immensely popular strategy computer game from the mid-1990s where users design a functioning city from scratch. Initially, some of the tops of buildings look humorously similar to ones found in downtown Auckland, and by the same token there is a water’s edge off to one side. Look a bit longer and one realises Simulations is not based on any specific geography but built upwards from a grid of highways and electrical farms; though by producing a sense of familiarity its generic nature works both ways to comment on the underlying principles of our own city. Importantly, what this kind of model shows is a city constructed of buildings not people, and as an artwork evokes a sense of the underlying abstractions or code that a capitalist system requires to function—with its emphasis on trade that is driven by profit and competitive growth.

In the silo adjacent, the second billboard illustrates the same scenario near obliterated by a pixelated blue that sweeps downwards across the frame, depicting a digital tsunami through which the tops of several tall buildings are just visible. It is a satisfying, yet spooky development to this ‘perfect’ image of city, a sequence that is unnecessarily reiterated in the original video version playing on the wall opposite. It is interesting to note that later expanded versions of SimCity 2000 featured “great disaster” options that required players to entirely rebuild the city as a result of flood, fire, nuclear meltdown, chemical spill, volcano, riots; the list is extensive—implying, as Simulations does, that total apocalypse or system meltdown belongs or is even fetishised within a capitalist imaginary.

Softly flickering in one of the rear spaces, Joanna Langford’s own city simulacra The beautiful and the damned is another work that playfully and provocatively connects digital practices to ideas of urban progress. Teetering towers constructed of old keyboards are backlit by LEDs that blink on and off, resembling high-rise buildings. Creating a tapered skyline, hot-glued power pylons made of bamboo sticks sling delicate bits of wire to either side. The beautiful and the damned has a chimeric quality—and like a lot of her work, appears held together by the slightest means, as if it might collapse at any moment. Stacking plastic keyboards like poker chips the sculpture is both beautiful and precarious, successfully alluding to the hasty, speculative investment practices that charmed the world market with the rise of the Internet during the 1990s. And, installed within the architecture of the silo—with its dimly lit spaces, exposed concrete walls, and cinematic reverb—the kitsch sensibility of this 2008 work is effectively housed within a feeling of the contemporary.

Installation view of The beautiful and the damned (2008) Joanna Langford. Photo by Sam Hartnett

Nearby Bellamy’s video Avail is projected onto a tall free-standing screen and accompanied by the ambient soundtrack mentioned earlier, whose sound travels freely in this exhibition. What was originally written as a jingle has been drawn out to several hundred times the playback time to reveal a dark and atmospheric structure of sound. In the video, another contradiction of scale is also processed; as we gaze at a soap bubble magnified to micro-detail, the surface of which appears as churning liquid containing all the colours of the light spectrum. Swirling with colours that, like molten magma, read as heat, and as artificially bright as they appear, suggest they might be hazardous, the connotations are not micro but macro; the fact that we don’t really know what we are looking at taps into a kind of amorphous unease about the global reach and invisibility of toxic chemicals.

Miranda Bellamy, Avail (2011) HD video with sound, 12:24 mins looped, sound design by Chris Miller. Courtesy of the artist

Shahriar Asdollah-Zadeh’s Pale blue dot juxtaposes an email conversation with a NASA aerospace engineer about space exploration, global peace and migration with a series of small abstract paintings drawing on Middle Eastern geometries and architecture from 10th-16th centuries. The content is not incompatible, but presentation of these two things within the same work is difficult. As viewers, it’s as if we miss a step between understanding the impetus to create paintings and the politics brought into view by more discursive means.

In the context of THE HIVE HUMS WITH MANY MINDS, the mounting and framing of these modest works on paper appears commercial, and interrupts the ability to read the works as a part of the complex conversation which the email handout so clearly communicates. The edited interview contains a fertile and politically engaging discussion about the positive potential of Middle Eastern diaspora and the need for a shift in attitudes of developed countries such as New Zealand receiving migrants, in the interests of realising the intellectual and creative contribution these people could make. Asdollah-Zadeh’s act of soliciting opinions from an unexpected source further emphasises the need for radically new perspectives.

In the spaces between silos, Tim J Veling, Louisa Afoa and Salome Tanuvasa’s work address the pressures of urban space from the perspective of a lived reality, returning the focus to the local that was a key theme in Part One at Te Tuhi.

Louisa Afoa’s 23 Years combines spoken testimony with her mother with shaky video footage shot around the family home. Addressing an encounter with a representative of government agency Housing New Zealand, 23 Years conveys an intimate and matter of fact message about the true stakes of the housing shortage in Auckland for many low income families.

Tim J Veling’s six documentary photographs capture examples of the support structures that were quickly erected after the earthquakes in 2010/2011 to prop up unstable architecture. The structures act as metaphors for the social improvisation and collectivity that emerged within neighbourhoods in the immediate aftermath of the quakes, but there are other readings available as well. In an interview with Radio NZ (May 8, 2016) Veling explains that a fence might be propped up indefinitely instead of pulled down or fixed; a typical example of the kind of frustrating systems in place for local residents waiting to receive due compensation, as well as permission to move forward with rebuilding their lives.

Salome Tanuvasa’s installation Appreciation tentatively marks out a space of ambivalence when thinking through urban space, looking at examples of entropy occurring in commercial or interstitial spaces. With inkjet photographs casually arranged in one of the grey alcoves designed for the mostly wall-based works in this show, Tanuwasa’s arrangement is instead quietly sculptural. The placement of images—on a glass cabinet or slung over a couple of pieces of brick tile—brings a quotidian feeling of searching and precariousness prompting one to consider the appearance of urban space as offering little sense of meaning or orientation. A humble contribution to the works in the show.

Despite the scope of the framing conversation of THE HIVE HUMS WITH MANY MINDS—globalising infrastructures and the way people live within the realities shaped by these—and the fact that each work is rewarding to spend time with—it’s difficult to read the works against the curatorial sub themes or threads which include the urban, industrial and digital. As with Part One at Te Tuhi, largely the works are not arranged according to these categories or a particular grouping of ideas, but in terms of their practical use of space. However, the architecture of the host venue—six connecting cylindrical interiors with its incredible sonic qualities—and the melodic bridging from the audio drone in Bellamy’s Avail written with musician Chris Miller (a connector piece similar to Rangituhia Hollis’s Oho Ake in Part One) both help to bring together site and many of the works into unison making it easier to envisage the "hive mind" used as a conceptual framework for the exhibition.