Oftentimes at twilight I find myself seated at a bus-stop awaiting carriage home. I generally frequent the same stop, where the seats are placed generously to afford a view of the city, though not from any great distance… Across the broad street from my position buildings rise—teeth, battlements or monoliths—thirty flights against the vaster reach of sky.

I have no pressing matters I can attend to whilst sitting there—no goals to achieve nor expectations to meet. Accomplishing little but witnessing the passage of time, I often get to wondering about the value of things, the way we think. For example there is a point where day becomes night, where a switch occurs between opposites… This moment somehow never arrives to announce itself, so I have to read the herald of night into inconspicuous details

The above text is extracted from a short piece of writing written by John Ward Knox for an exhibition by Fiona Gilmore at now defunct artist-run Newcall Gallery in Auckland back in 2008. Six years later, Ward Knox has just had his first exhibition of moving image works, along with being at Robert Heald Gallery, Wellington.

I return to this piece of his writing, from the year of Ward Knox’s graduation from Elam School of Fine Arts, because it makes clear to me the sustained nature of Ward-Knox’s distinctive enquiry as an artist since. A conceptual enquiry that has involved more dramatic shifts in media and idioms than even those of his contemporaries. For a viewer raised on old hat expectations that an artist stick to their knitting in one media, Ward Knox’s ability to excel in finding new vitality in everything from detailed illustrative drawing to minimalist sculpture, while making them so entirely his own, challenges impressively. And now video.

Ward-Knox has an abiding interest in exploring the material world between objects - the moving fabric of light, air and water in relation to body and a space. Heightening a consciousness of the transitional, ephemeral nature of the screen that reflect things. In effect much of his work has always been about the moving image.

In this early above text Ward-Knox goes on to write that Gilmore is offering us “a chance to slow down our expectations for gratification, to relish time spent during periods of transition. What we encounter is not a transaction, we do not enter the gallery and leave having made a cultural purchase, an intellectual product akin to “I came, I saw, I conquered”, but the opportunity to witness a series of infinitely different scenarios, played out inside of a continuum that purposefully eludes classification. Like finding ourselves in the shadow of a passing ship.”

Beautiful. Similar thoughts can be applied to this recent exhibition. For viewers, the sense of a continuous movement rather than a "got ya" moment. (Except of course we are now in a dealer gallery, and behind the scenes transactions are required, and a work will be purchased, a buyer caught). But beyond the street’s hubabub artist and dealer are careful to ensure this space off Cuba Mall is a calm container for a different kind of experience.

There’s an interest in the gentle transformation of things through actions that lead with body and with light. The movement between states rather than absolutes. This artist catches transition like catching a breath. The videos and paintings alike feel like containers for the breathing fabric of the world. It forces a slow down to reconsider the value placed on things. A better awareness of our lightness of being. The magical slow flicker of the atmosphere around us.

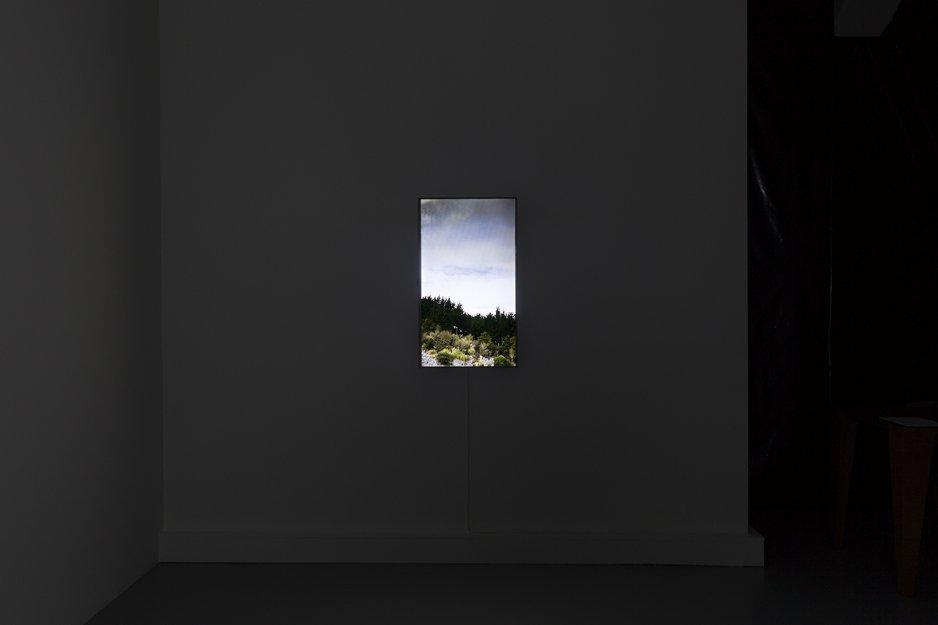

Emphasising Ward-Knox’s conceptual mode of enquiry beyond media, this recent exhibition is boldly and rather smartly divided into two sequential parts. Part one (24 September-4 October) the videos in the blacked-out gallery. Part two (9-25 October) the windows returned, the space once again white.

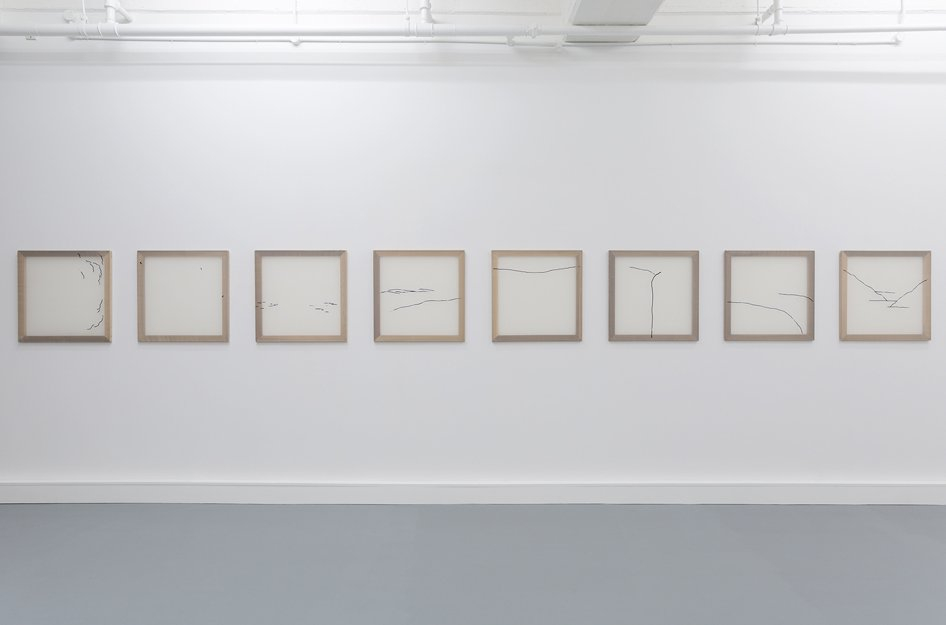

Part two is a set of arcylic paintings on silk stretched over wooden frames. They are in stark contrast to the intense detail across the surface and use of found imagery in Ward Knox’s more familiar paintings and drawings. Using a very sparse notation of fluid line, like graphs recording waves or other movement of figures in time, they resemble action drawings. Yet again the artist successfully collapses old housing—they are not one thing or another.

Installation view of along with being (ii) (2014) John Ward Knox. Courtesy of the artist and Robert Heald

Moving image is not just created by the action of line. One set of paintings employs two layers of silk, with both sides of the frame are stretched on and a membrane space between the two surfaces. This provides a simple kind of flip drawing or animation between the lines on either side.

Particularly strong are of set of eight canvases (No Title), that in their hanging resemble a series of film frames. Reductive plays with calligraphic-like line, they retain an open abstract agency whilst also giving a light impression of a seascape, a mountainous harbour entrance and a waterfall (shade of McCahon’s Fall series), amongst other things. Like the videos they are impressionistic.

Installation view of along with being (ii) (2014) John Ward Knox. Courtesy of the artist and Robert Heald

Recalling Len Lye’s ‘art in motion’ mantra, they could even be imagined as stills from the era of direct filmmaking, except that they exploit their independent isolation from each other as separate frames. From frame to frame line jumps animatedly into new arrangements, resisting any easy continuity. Yet stylistically they somehow remaining successfully one breathing body. The marks ignore the frames, sometimes found across the silk areas that are stretched over the top of the visible frames. It is as if nature is in control, escaping attempts to be contained by anything other than light and motion. In the first painting in the series there are clusters of short waved lines suggestive of clouds. They also suggest air gently blowing across all of the silk paintings, shifting the lines into new arrangements like a breeze on sticks in water.

For the video part, Heald had already blacked out the windows of the gallery for a Jae Hoon Lee show directly prior (the works share a similar meditative buzz—fixed position camera on slowly moving landscape). The space was very dark—for a month the only light available to Heald at the gallery desk was from the errie glow of his laptop. As a young dealer Heald is prepared to go to great lengths to ensure attention to the fine, visual shifts with materials the artists offer.

Isn’t this blacking-out providing viewing conditions for the work that collectors are unlikely to manage in their future presentation of the work? I prefer to think that the dealer is raising the bar for the treatment of video. This care is seen in other aspects of presentation—sleekly, darkly framed screens hung vertically, no intrusive product labels, and cabling lost to the darkness.

Easily the strongest of the three videos for me is Would. It is of a wood, scraggly Pinus Radiata, presented at a short distance in reflection in still lying water. There is a layering from bottom to top of scrubby toi toi dotted bank, forest and sky. The sky takes up just over half of the image’s frame so that, reflected in water, it carries the work’s abstract, fluid weight. It is a pleasant but commonplace rural New Zealand landscape—all clinging exotic commercial planting. Not what one would call scenic.

Just under six minutes in length, in Would the water surface becomes a second lens for the imagery (think of those two screens of silk). The landscape is made unconcrete, a liquid membrane turning the world mesmerically into jelly. Time is manifested through the shifts of wind on water.

Still from Would (2014) John Ward Knox. Courtesy of the artist and Robert Heald

It is unclear whether the artist has interfered in the scene – manufacturing movement of water for example. This is common of Ward-Knox’s light touch. I’m reminded again of Len Lye. Of his suggestion in his essay ‘Film-Making’ of movement as a function of the consciousness of time: “Up to a certain point we must leave physical things alone and let them speak for themselves, in movement.”

The close attention to surface with the aid of the camera sees natural effects that look remarkably like digital layering and glitching—in reality surely just the movement of a body of water.

This is enabled by the camera’s unusually close proximity to the surface of the water, playing all sorts of tricks with your perception in terms of what is reflected back. Simple but effective. The smallest, most inconsequential of changes register powerfully. The removal of space between viewer and the water shifts perceptions. We are tilted unusually, looking down but also in reflection up. There are grey-brown blotches. Is the sky dirty. The water? The camera lens? The work touches gently on our need to look after our water, our air, our earth.

You want drama? Lulled into a different pace, your viewing state is briefly tipped violently by the rupture of the surface by a drop of water. The snowglobe is shaken. Again, was this moment imposed? It’s difficult to track when it occurs. The moment is quickly subsumed. I feel a dangerous lack of control over this world as viewer. I’m reminded suddenly of the rupture and resulting liquefaction of the earthquake.

A second water work lacks this tension, but remains bequiling. Reflected askew in dappled water is the bridge of an expensive motorboat. An image of luxurious leisure to meet the richness and breeziness of the video. I’m reminded of a great Ward-Knox painting I saw at the Heald stand at the Auckland Art Fair 2011 in the Viaduct Events Centre (surrounded by gargantuan motoryachts). The billowing sails of a yacht on the harbour at full throttle. Even cheekily in that context, the work was still clearly more about the atmosphere and space created, than actual boating.

No glamour video, the camera picks up the detritus and contaminated water slowly moving through a marina. The boat is shadowy structural matter in the background, playing in tension with the slick movement of the surface of the water.

Still from Visions (2014) John Ward Knox. Courtesy of the artist and Robert Heald

The third video is quite different again and speaks more directly to Ward Knox’s engagement with direct action through body (I’m back with Lye again). The view is of a nondescript ceiling with a bare lightbulb shifting in position with the regular movement, in and out, of the camera. The central point of interest becomes the light coming in and out of focus, radiating layers of light. An idea moving in and out of clarity but never fixed.

Still from Ellipse (2014) John Ward Knox. Courtesy of the artist and Robert Heald

The camera’s steady natural movement is dictated by its placement on the stomach of the sleeping artist. So we have an experiment in how the camera’s movement might be controlled by the artist’s body beyond awake consciousness—a different kind of action drawing, with the lightbulb that familiar symbol of conscious thought. The video has warmth.The container of the room it depicts becomes like the rising and falling belly of the body, the light wobbling like a belly button. Expansion and contraction sees the world like the skin of an inflated balloon, tough but fragile.

The simplicity of the performance harks back to post-object video of the 1970s. In fact I’m reminded across all three videos of both Phil Dadson’s early and more recent video work, where there is an attention to the movement and breathing of the body in relation to landscape.

Light and beguiling, there is however a distinct conceptual proficiency at play with Ward Knox’s experimentation with the space between artist and the world. I’m steadied and made aware. I stop multitasking. I feel the breeze and breathe.